By Daniel Buck ✐

Special to Peruvian Times ☄

“A matter of wife or death” at the point of Peruvian dictator’s revolver, or deadbeat dad spinning yarn of sex and political intrigue to cover his tracks?

Some 75 years ago, Miraflores resident Mercedes de la Quintana informed the U.S. government that she and her children had been abandoned by her husband years earlier and were now destitute. Her husband, Lewis M. Clarkson, responded by filing a marriage annulment proceeding in district court in Washington, DC, where he was living with his current wife.

Some 75 years ago, Miraflores resident Mercedes de la Quintana informed the U.S. government that she and her children had been abandoned by her husband years earlier and were now destitute. Her husband, Lewis M. Clarkson, responded by filing a marriage annulment proceeding in district court in Washington, DC, where he was living with his current wife.

Perhaps Clarkson thought that would put an end to the matter. He was wrong. An alert Washington Post reporter saw the filing and two days later, September 15, 1937, published “D.C. Father, Wed ‘at Gun Point,’ Fights Peru Paternity Claim.” This was “a story so shot through with revolutions and intrigue,” the reporter wrote, “that movie audiences would classify it as a thriller which never could have happened.” Well, not really. Not only did it happen, the real story of Lewis Clarkson is even more bizarre.

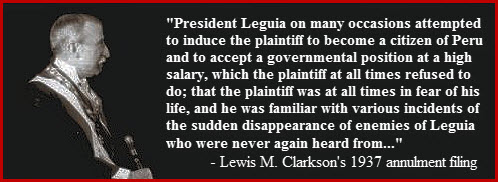

According to Clarkson’s “Bill of Complaint for Annulment,” on file in the National Archives in Washington, he had gone to Peru to work for a U.S. company, and in 1924 became acquainted with “Señora Mercedes de la Quintana Viuda de Ludewig,” a woman “of bad reputation” who “was commonly known to be involved in Peruvian political intrigues and to be supported by various prominent Government officials, including the then-president of the Republic, Augusto B. Leguía.” Clarkson averred that he had only visited Quintana in her home once or twice, but that when she turned up pregnant Leguía warned him that if he didn’t marry her, “he would be ‘accidentally’ shot.” Clarkson and Quintana were married March 9, 1925. Clarkson said that “four armed secret service men” escorted him to his wedding.

Clarkson said he had never had sex with Quintana and thus could not have been the father of her child, that they separated in the summer of 1925, and that in April 1926, Quintana gave birth to another child, who was also not his. Later that year, Clarkson persuaded Leguía to allow him to return to the United States to help resolve a Peru-Bolivia border dispute (Peru’s border disputes at the time were with Colombia and Chile), but not before forcing him, once again under armed guard, to register both children at the U.S. Consulate as his. Clarkson said that he returned to the United States in February 1927. The following year, friends in Lima told him that Quintana had died, and that he heard nothing else about her until 1937, when she petitioned the U.S. Department of State for assistance.

Leguía, the man Clarkson claimed to have tangled with, was president of Peru twice, 1908 to 1912 and 1919 to 1930, when he was deposed and imprisoned, dying in 1932. Hardly five feet tall, he was a reformer, a maverick, and increasingly during his second tour in office, the 11-year oncenio, an autocrat. One historian described him as “a self-made man who had gained entrance to the oligarchy by virtue of his talent, charm, and business success.”

Wire service versions of the Washington Post article in other papers varied in the details. In one, Clarkson declared that Quintana was Leguía’s mistress, implying that the forced marriage was arranged to legitimize his offspring. Decades later, a genealogical website, “Descendants of Phillip F. Clarkson,” improved the tale even further, reporting that Clarkson had married “the daughter of the Peruvian president,” though not at gun point, and when a revolution overthrew the government, Clarkson “escaped over the Andes with a price on his head,” his wife dying along the way.

Leguía was, indeed, during his presidency rumored to be a notorious womanizer, discretely receiving lady friends through a side door of the Government Palace.

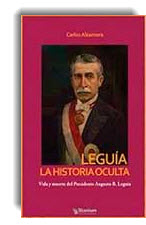

In his biography of Leguía, published earlier this year, Leguía: La Historia Oculta, retired diplomat Carlos Alzamora noted there were several extramarital affairs carried on by the ex-president, and wrote that at least three children were conceived from these relationships.

In his biography of Leguía, published earlier this year, Leguía: La Historia Oculta, retired diplomat Carlos Alzamora noted there were several extramarital affairs carried on by the ex-president, and wrote that at least three children were conceived from these relationships.

Alzamora did not, however, identify the names of Leguía’s mistresses.

So who was Lewis Clarkson? The Peruvian Times has determined, based on a review of newspaper accounts and court, census, consulate, and passenger-ship records, that he involved himself in a number of misadventures, chiefly of the adulterous, matrimonial and bigamous variety. His misadventures were decidedly less discreet than Leguía’s.

Clarkson was married as many as four times, and a bigamist at least twice. He abandoned his 1937 annulment complaint, meaning that he remained married to Quintana and his then-current wife.

Clarkson was born February 9, 1891, in Brooklyn, New York. He grew up near Bay Ridge, an Irish and Italian neighborhood. In the early 1910s, he married a woman named Side (or Sida), and had two children, Noel and Albert. Shortly thereafter, he abandoned his family. His wife ended up in a sanatorium and his children in an orphanage. He first went to Peru in 1917 to work as a bookkeeper for the American-owned Cerro de Pasco Corporation, at the time the premier mining operation in Peru. His 1919 passport photo depicts a slender, winsome young man, with wavy dark hair, wearing a suit and tie. He looks like a charmer; he could pass for Michael Cera.

A month after securing the passport, the charmer ran off with Hulda Skinner, the Danish wife of Victor Skinner, an American co-worker at Cerro de Pasco and a veteran of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Hulda told her husband she was going to the United States for an operation, but upon arrival had a cable sent declaring that she had died in an automobile accident in Arizona. He dispatched his sister to install a monument on her grave. Unable to find her grave or any record of her accident, the sister went to the police, who circulated her photograph as a missing person.

A few months later, Clarkson and Hulda returned to the United States from Mazatlan, Mexico, where they were living, and were arrested in El Paso, Texas. On July 19, 1920, he was charged with violating the Mann Act – transporting her from Nogales, Arizona, to El Paso, Texas, “for an immoral purpose . . . unlawful sexual intercourse” – and she with entering the United States without a passport. The El Paso Herald reported the arrests, below a droll headline: “Lack of Grave And Tombstone Leads to Arrest, Ending Peruvian Romance.”

Clarkson and Skinner were released on bond, and a few months later the New York City Department of Public Charities, alerted to Clarkson’s arrest by persons unknown, told the federal authorities that he was wanted in that city for having deserted his family. Scheduled to be arraigned and enter a plea in Tucson, Arizona, on January 31, 1921, Clarkson and Skinner failed to appear.

A few months later, Clarkson, now going as Louis Boyton Merrill Clarkson, resurfaced in Guatemala City, Guatemala, where he applied for an American passport. He said that he was representing a New Orleans company, Osigian Silk Industries, and was married to Helen Owens, about whom nothing else is known. The company’s controversial founder, Dr. Vartan K. Origian, who claimed that he could control the color of a silkworm’s silk by adjusting its feed, was attempting to set up mulberry tree plantations in Texas, Louisiana, and Central America.

A couple of years later Clarkson was back in Peru without Owens and wedded, at gunpoint or not, to Mercedes de la Quintana. In February 1927, he was on a steamer bound for New York City from Callao. Two years later, now in Silver City, New Mexico, Clarkson married Elizabeth Pierce, reportedly a descendant of President Franklin Pierce. They soon had a daughter, Luisa, and by the mid-1930s the family was in Washington, DC, where he was working for the U.S. Securities and Exchange commission (SEC) as an accountant, an odd profession for a man who could not keep track of his marriages. Clarkson must have finally settled down; no more misadventures were reported, and he died in 1970 in a Washington suburb.

What became of Quintana and her children is not known, nor do we have her side of what can only be described as a convoluted telanovela that “never could have happened.”

But one way or another, it did.

Daniel Buck is an independent scholar and freelance author who has written extensively about Andean history, as well as being a member of the advisory board of the Wild West History Association. He was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Puno, 1965-1967. Dan lives in Washington, D.C.