The Vilcabamba area, and Espiritu Pampa –known for its Inca history and where recent excavations have unearthed the tomb of an earlier Wari leader– has attracted both archaeological and geographical explorers for many decades, and many Peruvian Times writers among them. The following is a report by Gene Savoy in 1964, taken from the Peruvian Times archives. —

PART 2: Andean Air Mail & Peruvian Times, September 18, 1964

(See Part 1: Discovery in Vilcabamba)

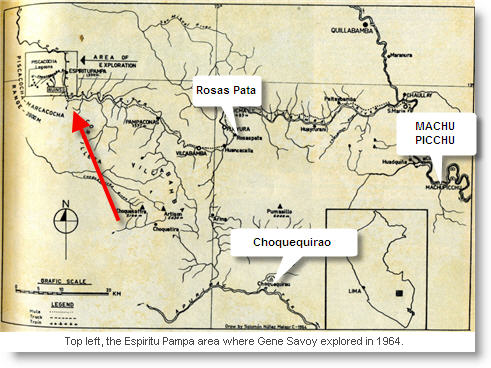

Gene Savoy, North American explorer and author, who over the past six or seven years has been engaged in aerial and ground exploration of a series of pre-Incaic ruins in the western Andes north of Lima, mainly in the Department of Ancash, has recently turned his attention to Incaic archeological remains in the Vilcabamba Cordillera of Southern Peru — specifically, Espiritupampa ruins at the foot of the Marcacocha and Piscacocha mountains, approximately 100 km west by north of the famous “lost citadel” city of Machu Picchu.

Although the existence of the Espíritu ruins has long been known (they were investigated by Hiram Bingham in 1911, prior to his discovery of Machu Picchu), the fact that they are of far greater extent than was previously realized has only been determined by Mr. Savoy’s recent explorations in company with his associate Douglas Sharon and Antonio Santander Cascelli, of Cuzco, well known Peruvian engineer and explorer, who had the Government contract to clear the ruins of Machu Picchu in 1934. This new information has led to the conclusion that Espiritupampa may well be an outlying section of the long-sought “last refuge” of the Incas. A corollary theory has also been advanced that this site may well have been the original home of the Incas from which this dynasty sprang before the founding of Cuzco.

Although the existence of the Espíritu ruins has long been known (they were investigated by Hiram Bingham in 1911, prior to his discovery of Machu Picchu), the fact that they are of far greater extent than was previously realized has only been determined by Mr. Savoy’s recent explorations in company with his associate Douglas Sharon and Antonio Santander Cascelli, of Cuzco, well known Peruvian engineer and explorer, who had the Government contract to clear the ruins of Machu Picchu in 1934. This new information has led to the conclusion that Espiritupampa may well be an outlying section of the long-sought “last refuge” of the Incas. A corollary theory has also been advanced that this site may well have been the original home of the Incas from which this dynasty sprang before the founding of Cuzco.

In any event, the new discoveries have served to create a resurgence of speculative interest in this age-old mystery. With Government assistance Mr. Savoy is now organizing further exploration in the area, designed to determine the full extent of the ruins and by clearing the heavy mantle of vegetation (including trees up to 200 feet tall) grown over the area during the past 400-odd years, making the site available for archaeological and historical research. (Pending the initiation of work on clearing the site, Trevor Ambrister, contributing writer, and William Bridges, of The Saturday Evening Post staff, who arrived in Lima last week to report on the new discoveries, have gone on to Bolivia to gather material for another article. They plan to return to Lima and make the flight into Espiritupampa by helicopter within the next two or three weeks.) Further information on the discovery will be found on the accompanying pages.

VILCAPAMPA GRANDE

Translation and condensation of a preliminary report on the field exploration conducted in the Vilcapampa Grande or Espiritupampa area, District of Vilcabamba, Province of La Convención, Department of Cuzco. Prepared by Gene Savoy, August 14.

To: Dr. Luis Valcárcel – President, Patronato Nacional de Arqueología, Lima.

Mr. President:

I am pleased to inform you of recent field operations conducted by the Andean Explorers Club (Club Andino de Exploradores) in the region known as Espiritupampa, Marcacocha and Piscacocha in the general area of the Chontabamba River in the valley of Concevidayoc, District of Vilcabamba, Province of Convención. The area lies at approximately Longitude 73ºO’ West and Latitude 13ºO’ S. Members of the expedition included Douglas Sharon, International Secretary of the Club, Antonio Santander Cascelli and myself. We were accompanied by Víctor Ardiles, Governor of the District of Vilcabamba. The fundamental purpose of the expedition was to make a general reconnaissance of the area in question in hopes of locating the final refuge site of Manco II and his three sons, i.e., Sayri Tupac, Titu Cusi and Amaru Tupac, the Inca chiefs who staged a rebellion against the Spanish crown, and, as we learn from ancient chronicles, settled in the area known as the neo-Inca state of Vilcabamba, Vilcapampa, Willkapampa or Huillca Pampa, etc.

As you may know from the various newspaper reports that have been published, our first-phase explorations were conducted in the vicinity of Espiritupampa, first reported as an archeological site by Hiram Bingham (see Lost City of the Incas, 1963, New York, Atheneum, pages 126-140; Harper’s Magazine, 1914, Col. 129; The American Anthropologist, 1914, New Series, Vol. 16) which was, according to the reports, explored in part. As my report will show, Mr. Bingham did not penetrate deep into the lower pampa known as Espiritupampa or Eromboni Pampa, due to the dense over-growth of the tropical rain forest, lack of time and personnel, and other reasons mentioned in his reports.

Owing to the fact that our expedition employed some 70 part-time workmen, we were able to explore or clear most of the 40,000 square meters of Espiritupampa, which, as I have noted, is covered with heavy growth and large vine-covered trees which reach upwards of 200 feet. In view of this abundance of tropical vegetation, visual observation, e.g., such as by binoculars, telescope, helicopter or airplane, is of no practical use or value as the eye cannot penetrate the forest. Our earlier plans called for aerial reconnaissance but this plan was rejected with the knowledge that it would serve no practical purpose. We did discover later, however, that helicopters can be used for the transportation of men and equipment in the area if certain preliminaries are met, viz., familiarity with the terrain, previously prepared landing sites, etc.

Our examination of the first pampa, known as Espiritupampa, was detailed and comprehensive in certain areas specifically selected. I chose a section of six groups of ruins, plus a seventh for documentation for various reasons, mostly due to practical considerations, e.g., accessibility of the location, willingness of the men to work in this area, weather conditions, etc. In total some ten other groups were studied, plus numerous smaller sites, which will be dealt with in my final report.

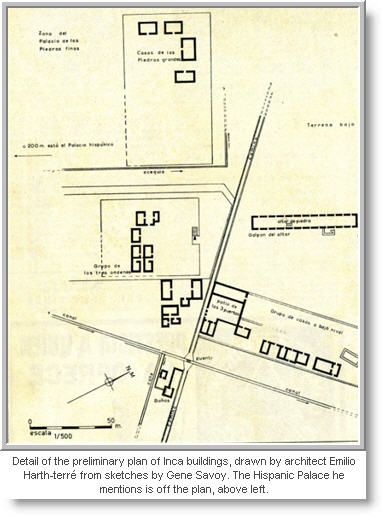

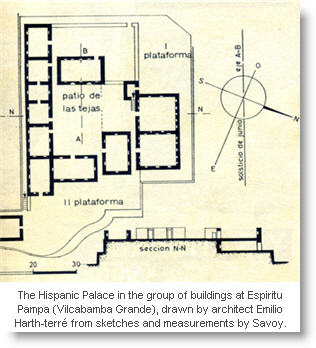

From the plans attached,* viz. Preliminary plan of the Espiritupampa area and the Hispanic Palace in this zone, you will be able to distinguish the architectural characteristics, dimensions, to scale, and design of the ruins under study. My final report will deal with other areas included in our ground examination covering an area far more extensive than Espiritupampa (1400 meters altitude). Our survey extended far up into the areas directly above Espiritupampa beneath the Marcacocha-Piscacocha range, into the zones indicated on my map as: (1) Rinconada-pampa; (2) Chonta-pampa or Rayme-pampa; (3) Manco-pampa or that area bounded by the river Chonta-bamba and the unmapped river which I have named Manco II and its tributary, Tupac Amaru; (4) Wamanpuma Pampa and the area laying between Espiritupampa and the Machigüenga camp-site; (5) lower Marca-cocha and: (6) lower Piscacocha.

From the plans attached,* viz. Preliminary plan of the Espiritupampa area and the Hispanic Palace in this zone, you will be able to distinguish the architectural characteristics, dimensions, to scale, and design of the ruins under study. My final report will deal with other areas included in our ground examination covering an area far more extensive than Espiritupampa (1400 meters altitude). Our survey extended far up into the areas directly above Espiritupampa beneath the Marcacocha-Piscacocha range, into the zones indicated on my map as: (1) Rinconada-pampa; (2) Chonta-pampa or Rayme-pampa; (3) Manco-pampa or that area bounded by the river Chonta-bamba and the unmapped river which I have named Manco II and its tributary, Tupac Amaru; (4) Wamanpuma Pampa and the area laying between Espiritupampa and the Machigüenga camp-site; (5) lower Marca-cocha and: (6) lower Piscacocha.

We expect to conclude our second-phase operation over the next 60 to 90 days. At this time I can state that these areas contain archeologically unreported ruins of great importance. Our expedition had a duration of 37 days, 22 days at the actual sites in question. Since our operation was divided into two distinct phases viz., actual exploration being conducted by Douglas Sharon and myself and clearing conducted by Antonio Santander, we were able to achieve maximum results from an exploratory point of view. Due to my experience in various parts of Mexico, Yucatan and Peru, and that of my assistant, Douglas Sharon, we have been able to develop special techniques allowing a maximum amount of “positive” or “paying” terrain to be examined with a minimum of manpower-effort.

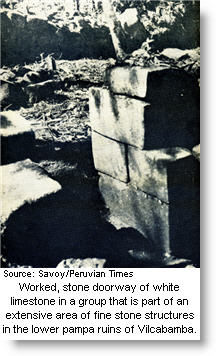

As previously mentioned, my examination of this archaeological zone was conducted from an historical rather than archaeological point of view. In my opinion the site can be considered to be Vilcabamba Grande, the final refuge of Manco II and his three sons. The evidence: e.g. extensive area of ruins covering many square kilometers, a minimum of four and a maximum of ten, revealing Inca design and craftsmanship; the abundance of Inca pottery (fragments); the Spanish colonial artifacts e.g., horseshoe, colonial-type tile; the interrelationship of Inca and Spanish influence and above all its location in the montaña all indicate to me an archaeological site unique and unequalled in all Peru.

The Spanish-type tile, for example, with the unmistakable Inca influence, i.e., serpentine incision, red ceramic-type paint, would appear to be conclusive proof that the site is late Inca. The fact it was removed from Spanish influence or areas colonized by the Spanish strongly suggests that the site was a refuge used by the last Incas caught up in the throes of a final struggle against the new conquerors. What else are we to deduce from this evidence? (Refer to the excellent commentary by Sr. Harth-terré, viz., “Tejas en el Palacio Hispánico” attached).*

My examination of the area has revealed an abundance of this tile littering the entire zone. My collection was taken from the Palacio Hispánico because of the superficial abundance of tile. But large amounts of this same material is in evidence in the general area. (One has only to scratch the surface with a machete to uncover tile fragments). This is indicative that large groups of buildings at this site were roofed with tile as opposed to the common thatch roof.

This finding would appear to be almost conclusive proof that the site in question was the final refuge of the last of the Incas. From historical records we know that this area was not colonized by the Spanish. The inhabitants of the area must have been Incas who had a knowledge of fabricating Spanish-type tile, possibly having learned this craft in Cuzco prior to their flight to Vilcabamba Grande or the tile must have been fabricated by the few Spaniards known to have collaborated with Manco II, or who were taken prisoner by the rebel Inca in his raids on Spanish supply trains between Lima and Cuzco.

Historical Examination of Available Accounts

Friar Diego Rodríguez de Figueroa states that he met with the Inca Titu Cusí in 1565 at the so-called site of Vitcos (Pitcos, Uiticos or Viticos), which is now generally believed by archeologists and historians to have been an Inca stronghold at the modern site known as Rosas Pata, across the Vilcabamba river from the pueblo of Huancacalle. This site is often referred to as the “young fortress” which fell to the Spaniards. Tito Cusi, as reported by Friar Diego, came from a remote capital stronghold, viz., Wilcapampa Grande, said to be two “hard days” or three regular days distance. He brought with him monkey, venison and macaw meat, as well as other products native to a tropical climate.

The archeological site being discussed in this preliminary report abounds with the above mentioned animals. If we accept that the Inca operated out of a site deep in the montaña and not the puna — as history suggests — then the site under study fits exactly with the location of Vilcapampa Grande.

The archeological site being discussed in this preliminary report abounds with the above mentioned animals. If we accept that the Inca operated out of a site deep in the montaña and not the puna — as history suggests — then the site under study fits exactly with the location of Vilcapampa Grande.

Bingham states, that from his superficial examination of Espiritupampa, “the site meets the requirements of the place called Vilcapampa by the companions of Captain Garcia” and that “at all events our investigation seemed to point to the probability of this valley (Concevidayoc) having been an important part of the domain of the last Incas.” He was disturbed, however, by the fact that according to Calancha, Vilcapampa the 0!d “was the principal and largest city in the neo-Inca state.”

Bingham’s examination of the area revealed that the ruins he examined were hardly representative of a city. This is due to the fact he did not push deeper into the pampas, it appears, for the archaeological remains, as previously pointed out, cover an extensive area. Furthermore, the archeological remains (as can be deduced from the small section shown in the sketch-plan) are of a complex nature suggesting a city layout as opposed to isolated ruins. Since the plan includes only a portion of the one site known as Espiritupampa and since there are several sites in the general area (which I have named Vilcapampa Grande), it can be seen that the sites are extensive and suggest an interrelationship. We have, then, a very rich archaeological sector hitherto unknown, except for those smaller sections examined by Bingham in the lower areas of Espiritupampa.

In review of Friar Diego’s account, we learn that Titu Cusi brought with him a number of Anti savages from the jungle. We can draw the conclusion that the Anti are in fact the Machigüengas, which now inhabit the immediate area (as they did in the period of Bingham’s explorations). I think this is an important historical point which can help us to evaluate the site in question.

To continue my historical analysis of the site, we know that the chronicles of Calancha and Ocampo indicate that the general area of the last refuge of Manco and his sons points to the Espiritupampa area (though the area is in fact larger than the small site known by this name), e.g., archaeological remains have been found to exist in the higher reaches of the Chontabamba river and its tributaries which flow out of the Marcacocha-Piscacocha chain and the lagoons native to this area — which we have found to be five in number. From a careful reading of the accounts which mention Captain Garcia and his pursuit and capture of Tupac Amaru — and a thorough knowledge of the area with which this report specifically deals — many interesting facts, or what appear to be facts, come to light.

We know that Titu Cusi built a residence down in the lower reaches of the montaña, viz. Pampaconas or Concevidayoc valley (Bingham beieved he had examined this residence near Espiritupampa, viz., at Eromboni Pampa). We also know that Captain Garcia, in storming the fortress-strongholds of the Inca’s refuge, had to pass over craggy heights surrounded by jungles. In my opinion neither Rosaspata nor Machu Picchu meets the requirements of the descriptions recorded. In view of my recent findings the whole study of Vitcos-Vilcapampa has been reopened. I believe this will add to our knowledge of the final days of the Incas.

We know that Titu Cusi built a residence down in the lower reaches of the montaña, viz. Pampaconas or Concevidayoc valley (Bingham beieved he had examined this residence near Espiritupampa, viz., at Eromboni Pampa). We also know that Captain Garcia, in storming the fortress-strongholds of the Inca’s refuge, had to pass over craggy heights surrounded by jungles. In my opinion neither Rosaspata nor Machu Picchu meets the requirements of the descriptions recorded. In view of my recent findings the whole study of Vitcos-Vilcapampa has been reopened. I believe this will add to our knowledge of the final days of the Incas.

If you will examine the sketch plan, note Galpón del Altar, the long structure measuring some 65 meters in length, and the large stone (marked Piedra Votiva) which measures some nine by ten meters and seven meters high — and I might mention that a stream runs through the general area marked Terreno Bajo (inexplorado) — some startling conclusions can be drawn (if one is familiar with history).

It will be remembered that Bingham was particularly searching for a large, white rock near a stream and a “long house of the Sun.” He was aware of the large rock at Ñusta Isspaña at the time, but could not, in his own words, locate another rock of this description nor a “long house.”

There are other pertinent facts which add to our understanding of this hitherto unexplored zone. For example there are archeological sites some two hard days or three regular days away from the lower Espiritupampa area, viz., up towards the Marcacocha-Piscacocha chain. What are we to deduce from this information? To be sure, ever since Sr. López Torres first reported existence of a city in this general area in 1902 (which caused Bingham to investigate the area in 1910) speculation has continued. But now we have factual evidence proving his claim. Just what site he reported on, as there are several, we do not know.

In my personal opinion, Mr. President, based on my preliminary observations, I am convinced that Espiritupampa and the largely unexplored adjoining areas were the site of the last refuge of the Incas. The immediate question is: how extensive are the ruins?

Equally, we must turn our attention to the possibility of valuable artifacts which may exist in the area. We know that the so-called “lost Inca treasure” has not been found, e.g., the large golden sun disk taken from the temple at Cuzco by Manco II and guarded by the last Inca, Tupac Amaru; in addition to other treasure such as the golden chain of the Inca Huayna. If this treasure exists — and, according to historical records, it was not found — then we may speculate as to its whereabouts. Tupac Amaru might well have taken it with him when Captain Garcia began his pursuit of this unfortunate Inca. On the other hand he may not have taken the treasure with him. As far as we know he did not have it when he was captured and taken to Cuzco for execution. If these objects exist they rightfully belong to the nation’s museums.

*Not published with this article.

Pingback: “LOOKING BACK: Part 2 – Vilcabamba Grande – ‘Last Refuge’ of the Incas” | Community Communiqué

Pingback: Morien Institute Terrestrial Archæology, Marine Archæology & Astro-Archæology News Headlines for March 2011 - morien-institute