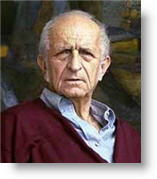

President-elect Ollanta Humala met Monday with the acclaimed painter Fernando de Szyszlo to discuss the creation of Peru’s Memory Museum.

President-elect Ollanta Humala met Monday with the acclaimed painter Fernando de Szyszlo to discuss the creation of Peru’s Memory Museum.

De Szyszlo was appointed president of the commission to create the Museum in September last year, after author Mario Vargas Llosa resigned from the post.

The museum, under construction on the cliffside overlooking the Pacific Ocean in Miraflores, will cost 100 million soles (about $36 million). Financing for the project includes 2 million euros from the German government.

The museum is to include photographs, audios and artistic work to acknowledge the victims of Peru’s political violence between 1980 and 2000.

“It is with satisfaction I saw the [president-elect’s] enthusiasm for the Memory Museum,” said De Szyszlo. “This seems important because the monument is to victims of terrorism, of violence.”

Humala, a military officer during the offensive against Sendero Luminoso and MRTA, is himself questioned for alleged human rights abuses in 1992 in the town of Madre Mia, in the Tocache province of the Upper Huallaga, a coca production area.

The museum is to honor the 70,000 people who died during the 20 years of political violence in Peru between the Maoist Shining Path insurgents and government security forces. The current exhibition, Yuyanapaq (To Remember, in Quechua), was originally opened in 2003 — after the presentation of the Truth and Reconciliation Report– and is temporarily housed on the 6th floor of the Museo de la Nacion.

According to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was headed by Salomon Lerner, the former rector of the Universidad Catolica, 54 percent of all deaths in the conflict were attributed to the Shining Path rebels. The armed forces were blamed for 30 percent, and most of the remaining fatalities were blamed on government-backed peasant militias. A greater number of the victims, by both sides of the conflict, were Quechua-speaking peasants in rural Andean communities.

Mario Vargas Llosa resigned from the Museum commission last year when President Garcia enacted Law 1097, which proposed a statutory limit of 36 months on criminal investigations into human rights abuses. Vargas Llosa described the law, which was eventually repealed, as a “disguised amnesty” for all military personnel who were responsible for counter-insurgency incidents, many of which are only being proven 10 or 20 years later as forensics unearth mass graves and other details.

“There is a fundamental incompatibility,” Vargas Llosa said, between backing the construction of a memory museum and enacting a law that was providing an escape hatch for the perpetrators of the abuses committed during the violence.

President Garcia also initially refused to accept the German government’s 2 million euro donation for the museum, on the grounds that the museum did not “reflect the national vision” of what occurred between 1980 and 2000. Garcia and the Apra party, as well as members of Keiko Fujimori’s Fuerza 2011, including former defense minister Rafael Rey and congresswoman Luisa Maria Cuculiza, have consistently rejected the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and its Report.