By Rick Vecchio ✐

Peruvian Times Contributing Editor*☄

The first time I laid eyes on Machu Picchu was 16 years ago, and even though I do not consider myself a particularly spiritual person, what I experienced in that moment was profound, and has stayed with me. It’s the same each time I return.

The first time I laid eyes on Machu Picchu was 16 years ago, and even though I do not consider myself a particularly spiritual person, what I experienced in that moment was profound, and has stayed with me. It’s the same each time I return.

For a long time, I’ve asked myself, why is that? This essay is an attempt to give that question a go.

Let’s start with a hypothesis: What makes Machu Picchu a cultural heritage of humanity is precisely that shared experience of awe and awakening — a sensation felt by millions of others who stood in that spot and saw and felt the same thing. In that moment, you are a little more connected to humanity.

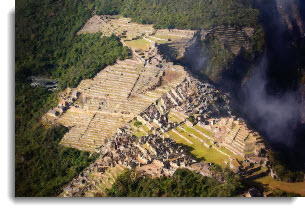

For more than 100 years, the poetic architecture of Machu Picchu, perched perfectly on the saddle of a mountain between two craggy peaks, has challenged adequate description.

Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, in his classic poem Heights of Machu Picchu, wrote:

Then up the ladder of the earth I climbed

through the barbed thickets of lost jungle

until I reached you Machu Picchu:

High city of laddered stone,

finally resident of what is earthly

you did not hide in the dormant raiment

George Kubler, the great 20th century art historian, wrote in 1960 that the “dimensions and directions of the town are ‘around’ and ‘up’ and ‘down’; the units of urban space are contoured terraces, rising by pyramidal stages and spreading across the saddle like a blanket of ribbed and stony weave.”1

On either side, the contoured terraces fall sharply away into “green-blue abysses” — a sheer drop to the jungle gorge below where the Urubamba River snakes almost completely around the towering citadel in a horseshoe bend.

Since its scientific “discovery” one hundred and one years ago by Yale professor Hiram Bingham, the question of why Machu Picchu was built and what purpose the incomparable stone city served in Inca society remains an enduring mystery.

Bingham, himself, got it completely wrong when he surmised that the sanctuary was the Inca’s last jungle stronghold, Vilcabamba. But try, as many have, to knock the man, he deserves full credit for revealing Machu Picchu to the world. Breakthrough research and new discoveries continue to reshape our understanding of the site.

In just the last few years, a small, but vocal, group of researchers have got behind an intriguing theory from Peruvian archaeologist Luis G. Lumbreras. He believes that Machu Picchu is in fact Patallaqta, a “Royal Mausoleum” built — much like the Egyptian pyramids were for the ancient pharaohs — to venerate the 9th Inca Pachacutec after his death.2

The widely accepted interpretation of Spanish chronicles is that Pachacutec arranged for his body to be laid to rest in Patallaqta, located very near or at present-day Qenqo, the ruins above the city of Cusco.**

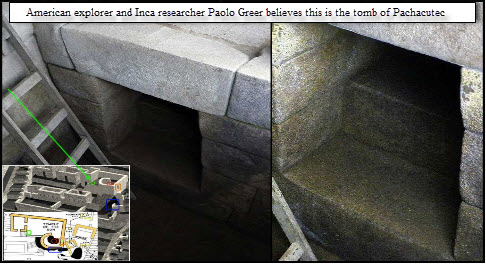

American researcher and explorer Paolo Greer has made it his mission to prove his version of the newer Patallaqta theory.3 He is convinced that a recently-excavated, underground Inca niche with fine coursed stonework next to the Torreon (or Temple of the Sun) at Machu Picchu is Pachacutec’s tomb.

American researcher and explorer Paolo Greer has made it his mission to prove his version of the newer Patallaqta theory.3 He is convinced that a recently-excavated, underground Inca niche with fine coursed stonework next to the Torreon (or Temple of the Sun) at Machu Picchu is Pachacutec’s tomb.

Paolo has proposed what many would consider a Don Quixote-esque search below Machu Picchu for the discarded remnants of a stone statue of the Inca ruler.

(He is also trying to organize new excavations of the colonial-era hospital of San Andrés in Lima to locate Pachacutec’s lost mummy. After the conquest, native worshipers hid the mummy in current day San Blas, but Spanish authorities discovered the clandestine shrine and Polo de Ondegardo brought it to Lima on the orders of the Marquis of Cañete. Multiple chronicle accounts say Pachacutec ended up buried somewhere in the hospital.)

Hiram Bingham’s academic descendants at Yale University reject anything close to the mausoleum premise: “Machu Picchu was not created solely, or even primarily, to legitimize symbolically Pachacuti’s rulership, although this is a major theme inhering in the site’s architecture,” wrote Yale anthropology professor Richard Burger and archaeologist Lucy Salazar.4

The main motivation for building Machu Picchu, they argue, was to provide Pachacutec, his royal entourage and guests a warm and pleasant “country palace” during the cold Cusco winter months of June, July and August.

A couple of weeks ago over coffee in Cusco, I ran the question by Peter Frost, the writer, photographer, lecturer and independent Inca scholar, whose opinion I greatly respect.

“The thing about Machu Picchu is that different theories come and go, gain sway, become the ruling paradigm, then go out of fashion,” Peter said. “The tendency of theorists of Machu Picchu is to fall into the trap of trying to reduce it to one thing. It was Pachacuti’s winter palace. It was Pachacuti’s mausoleum. Maybe it was all of these things.”

There’s always the chance that some new Chronicle or archival documentation will turn up, generating new theories, he said, “but we can’t prove any of them, really, without more research.”

In 1987, 46 lost chapters from Narrative of the Inca, published in 1557 by Chronicler Juan de Betanzos, was found gathering dust in the private collection of the Fundación Bartolomé March in Palma de Mallorca, Spain.

Betanzos was the official Quechua interpreter for the Conquistadors. His wife was the Inca princess Doña Angelina Yupanque, who had been betrothed in dynastic marriage to her half-brother Atahualpa before Francisco Pizarro had him murdered and took her as his concubine. She married Betanzos after Pizarro’s assassination.

Given his language skills and his wife’s first-hand knowledge of Inca royal lineage, Betanzos is considered one of the most reliable of the Spanish chroniclers.

His description of Patallaqta breathed life into Lumbreras’ mausoleum theory and launched Paolo on his quest.

It also made international news headlines again earlier this year when María del Carmen Martín Rubio — the Spanish historian who discovered the lost Betanzos chapters — proclaimed:

“I believe the original name of Machu Picchu was Patallaqta, which means ‘city of andenes,'” or “terraces.”5 ***

On the question of Pachacutec’s tomb, however, Martín Rubio said she didn’t completely agree with Lumbreras. At the Torreon, worshipers venerated a golden funerary bundle, imbued with the Inca ruler’s spirit — as well as clippings of his fingernails and hair — but not his actual mummy.

That was enshrined at the Coricancha Temple in the city of Cusco, the absolute earthly center of the Inca cosmos. The mummy was taken out and paraded for important religious holiday festivals.

So, is it premature to think about changing the name of Machu Picchu to Patallaqta?

Peter chuckled when I asked him that.

“The fact that it could be called Patallaqta and might have been used as a mausoleum for Pachacuti doesn’t mean it wasn’t used in all kinds of other ways, as well,” he said. “I don’t care what they call it, but I don’t think they’re going to change the name. The marketing people wouldn’t go for it.”

Peter said, personally, he remains most persuaded by the work of high mountain archaeologist Johan Reinhard, who suggests that Machu Picchu functioned primarily as a sacred center, where huge landscape alignments of mountain deities and celestial bodies converge.

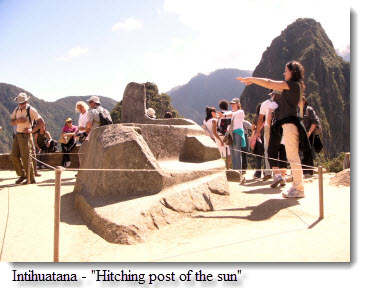

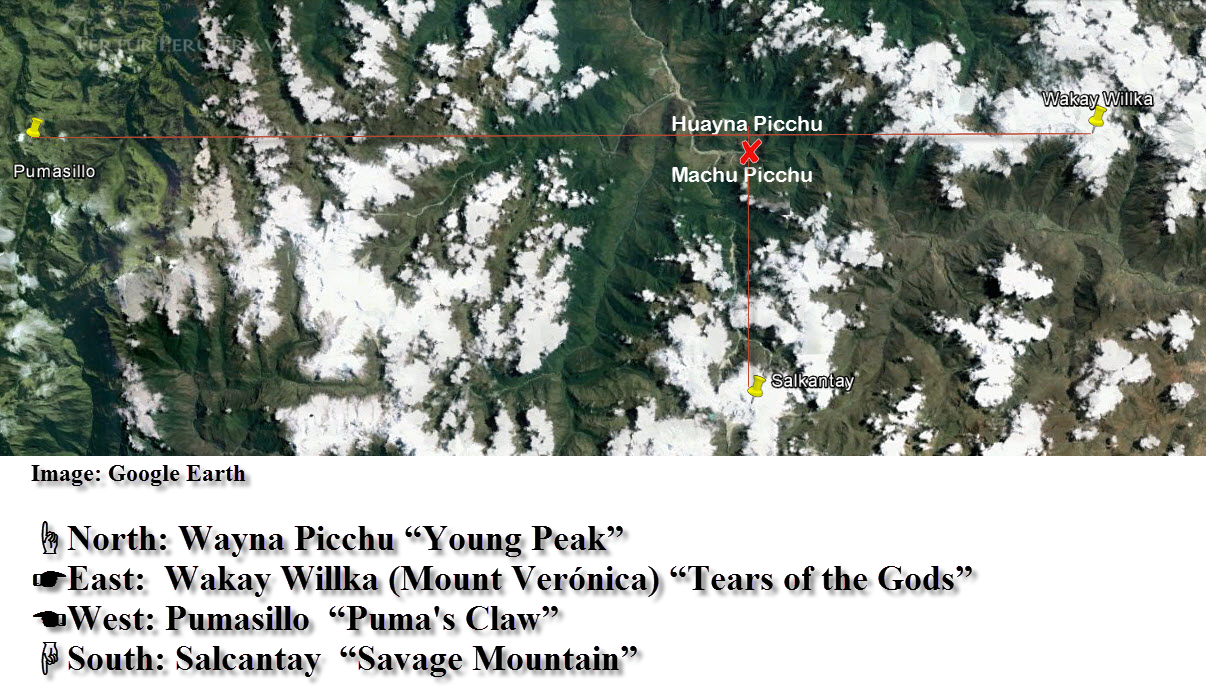

Reinhard showed how the Intihuatana, the hitching post of the sun, marks a geographic intersection, east-west and north-south, between five important mountains.6

These alignments remain the stuff of Inca legend: The Sun was ritually tied to the Intihuatana — the hitching post — at the time of the solstice, when it was farthest from the earth. The legend holds that the connection to Machu Picchu acted as a kind of cosmic lasso, preventing the sun from straying any further away on the horizon, ensuring its orderly orbital return.

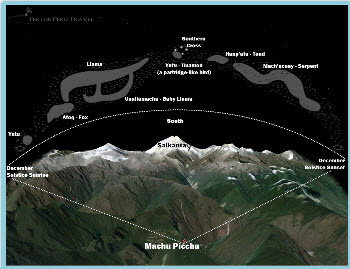

Looming above Machu Picchu, due North, is the ceremonial mountain peak of Huayna Picchu, while directly south lies Salcantay — one of the most sacred mountain “Apu” deities for the Inca.

In May, during the rainy season, the Chacana, or Southern Cross, rises to its highest point in the sky directly above Salcantay.

Surrounding the four Crux stars are other star groups and the Yana Phuyu (YA-na FOY-you), a river-like expanse of dark cloud constellations representing the spirits of the animals here on earth.

For the Inca, this corner of the Milky Way was integrally associated with rain and fertility.

On the December solstice, the Sun sets behind the highest snow peak of the distant Pumasillo mountain range to the West.

Click on image to enlarge

Twice a year, on the solar equinoxes, the Sun comes up behind the snow-covered peak of Wakay Willka (Mount Verónica) and sets behind San Miguel (Mount Vizcachani).

In 1989, Reinhard, Leoncio Vera and Fernando Astete, director of the Machu Picchu Archaeological Park, excavated a ceremonial platform atop the San Miguel summit, where the Inca had set a central rock upright to mark the precise equinox setting point.

Explorers continue to find similar, outlying astronomical markers left by the Inca.

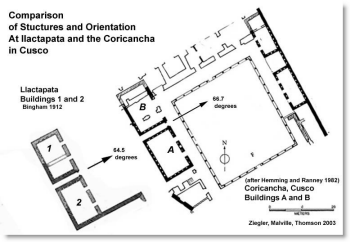

An expedition led by American archaeologist Gary Ziegler and British explorer Hugh Thomson in 2003 located Llactapata, an Inca ritual site about 2½ miles from Machu Picchu. The site had got a passing glance 91 years earlier by Bingham, but he failed to note down proper coordinates, and its location in the dense jungle cloud forest remained a mystery for decades.

It was Reinhard who rediscovered a section of Llactapata in 1985. Building on that research, the Ziegler-Thomson expedition made some fabulous new discoveries, presenting further evidence that Machu Picchu was the hub of a geographically vast complex of astronomical observatories, integrally connected with the Inca “cosmovision.”7

In one section, seven buildings, two courtyards and two ceremonial corridors were remarkably similar in their structure and orientation to the Coricancha Temple in Cusco. The long Llactapata corridors marked the rising sun on the June solstice and the heliacal rising of the Pleiades constellation — important dates in the Inca agricultural calendar — as well as providing a direct view across the Acobamba River to Machu Picchu itself.

In one section, seven buildings, two courtyards and two ceremonial corridors were remarkably similar in their structure and orientation to the Coricancha Temple in Cusco. The long Llactapata corridors marked the rising sun on the June solstice and the heliacal rising of the Pleiades constellation — important dates in the Inca agricultural calendar — as well as providing a direct view across the Acobamba River to Machu Picchu itself.

During the time of the Inca, Ziegler believes, Llactapata functioned as a sort of “bedroom community and cultivation area in support of Machu Picchu.” Travel between the two sites would have taken several hours on a then-well maintained Inca road, he wrote me in an email. The now famous Inca Trail continued past Machu Picchu, via Llactapata, onward into the Vilcabamba to a network of connected sites and roads, he added.

“I pretty much agree with Peter and Johan. I have concluded that important Inca estates, which Machu Picchu surely was, were multifunctional,” Ziegler wrote. “perhaps with a primary specific ceremonial focus, but included year round activities, state sponsored pilgrimages and may have served as a regional administrative center.”

The use and function of Machu Picchu may have changed over time under the administration of Pachacutec’s royal familial entourage, or “panaca,” following his death, Ziegler concluded.

As I wrote at the outset, every time I return and lay eyes on Machu Picchu, I feel that same jazzed sense of awe and awakening that clutched me that first time 16 years ago. Why?

Jennifer Moss Logan, an astronomer at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, makes a great point when she sums up her planetarium presentation on Inca astronomy:

We know from science that the Yana Phuyu dark cloud constellations — to which the Inca felt themselves cosmically connected — are actually formations of gas and dust blocking starlight from the depths of the Milky Way. These dust clouds are made up of tiny hydrogen atoms and grains of graphite and of silicon oxide the size of smoke particles, she says.8

“Today, astronomers tell us that our bodies — the actual carbon, oxygen, and iron atoms that are part of our bodies — are the materials forged in the exploding stars of long ago. As Carl Sagan, a famous astronomer, once said, ‘We are made of star stuff.'”

That’s what the science tells us.

So, she concludes, we’re not so far apart after all from the Inca in our cosmovision.

___________________________________

Bibliography

1. MACHU PICCHU by George Kubler, Perspecta, Vol. 6 (1960) The Yale Architectural Journal

2. Machu Piqchu, el mausoleo del emperador by Luis Guillermo Lumbreras, published in Machu Picchu: Historia, Sacralidad e Identidad Ed. INC (2005)

3. Machu Picchu: a revised history of discovery by Paolo Greer, PUBLISHED IN ESTER, ALASKA (2008)

4. Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous: Luxury and Daily Life in the Households of Machu Picchu’s Elite by Lucy C. Salazar and Richard L. Burger, published in PALACES OF THE ANCIENT NEW WORLD, Ed. Dumbarton Oaks (2004)

5. El nombre original de Machu Picchu fue “Patallacta” que significa “ciudad de andenes” NoticiasSer.pe

6. Sacred Mountains, Ceremonial Sites, and Human Sacrifice Among the Incas by JOHAN REINHARD AND CONSTANZA CERUTI, Ed. University of Texas Press (2005)

7. Machu Picchu’s Observatory: the Re-Discovery of Llactapata and its Sun-Temple by J. McKim Malville, Hugh Thomson & Gary Ziegler Ed. Longer English version of the article that was first published in the Revista Andina (2004, #39)

8. Astronomy in the Inca Empire – Jennifer Moss Logan, Denver Museum of Nature and ScienceNotes:

* Rick Vecchio is also director of marketing and development for Fertur Peru Travel, which is owned by his wife, Siduith Ferrer, and is a commercial sponsor of ANDEAN AIR MAIL & Peruvian Times. You can read more of his articles on the Peruvian Travel Trends blog.

**There are many other ‘Patallaqtas’ in and around Cusco and even close to Machu Picchu, with the same spelling or variants of the Quechua name.

*** The more widely accepted translation of Patallaqta or Llactapata is “high place” or “high town.”

If you like this article, please remember to share on Facebook, Twitter or Google+