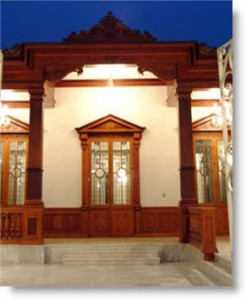

In brief. The museum is housed in the magnificently restored Casa Belén, home of José Baquíjano y Carrillo, Count of Vista Florida (1751-1818). It is now a memorial to Andrés Del Castillo, a young student who died tragically in 2006. The museum houses an outstanding collection of minerals, demonstrating their exquisite beauty and complexity and witness to the mining wealth of Peru. It also has significant exhibits of ceramic art from the Chancay culture (900-1400) as well as textiles from before 1532 and paintings from vice-regal times.

By Tony Darrington

All right, own up – who hasn’t heard of José Baquíjano[i] y Carrillo, Count of Vista Florída? Quite a few, I see. Well you should be ashamed of yourselves. If there were but a few that had redeemed the ‘intellectual honor’ of Peru in the run-up to independence – as, militarily, Grau, Bolognesi, Ugarte and Caceres (and thousands of men, rabonas and others) had sixty years later in the war with Chile – then José Baquíjano should be counted amongst them. Baquíjano was not only a leading intellectual figure in late vice-regal society and precursor of independence but also a founder of El Mercurio Peruano[ii], President of the Sociedad Amantes del País and sometime owner of Jirón de la Unión 1030, just off the Plaza San Martín, downtown Lima. That house has now been more than lovingly restored to become Lima’s newest museum: the Museo Andrés Del Castillo.

All right, own up – who hasn’t heard of José Baquíjano[i] y Carrillo, Count of Vista Florída? Quite a few, I see. Well you should be ashamed of yourselves. If there were but a few that had redeemed the ‘intellectual honor’ of Peru in the run-up to independence – as, militarily, Grau, Bolognesi, Ugarte and Caceres (and thousands of men, rabonas and others) had sixty years later in the war with Chile – then José Baquíjano should be counted amongst them. Baquíjano was not only a leading intellectual figure in late vice-regal society and precursor of independence but also a founder of El Mercurio Peruano[ii], President of the Sociedad Amantes del País and sometime owner of Jirón de la Unión 1030, just off the Plaza San Martín, downtown Lima. That house has now been more than lovingly restored to become Lima’s newest museum: the Museo Andrés Del Castillo.

We recently visited a museum that “sublime in its perfection, perfectionist[iii] in the quality of its restoration and restorative – personally – in the pleasure it gives to the visitor.” There are four sections of exhibit: historical legacy (the physical building and memories associated with it – prompted by a ‘long wall’ providing a detailed time-line); the mineral collection (which speaks directly of Peru’s wealth in natural resources and are objects of beauty –some stunningly so– in their own right); the Chancay ceramics; and a textile collection.

We recently visited a museum that “sublime in its perfection, perfectionist[iii] in the quality of its restoration and restorative – personally – in the pleasure it gives to the visitor.” There are four sections of exhibit: historical legacy (the physical building and memories associated with it – prompted by a ‘long wall’ providing a detailed time-line); the mineral collection (which speaks directly of Peru’s wealth in natural resources and are objects of beauty –some stunningly so– in their own right); the Chancay ceramics; and a textile collection.

But let’s return to the time-line on the “long wall” for a moment. It is 27 August 1781 and just four months after the battle of Checcacuppi[iv], which finally defeated the insurgency of Tupac Amaru and put an end to the dream of a “pluralistic” independence[v]. At scarcely 30 years of age, José Baquíjano y Carrillo had been chosen to deliver the address of welcome to the recently-arrived Viceroy Agustín Jáuregui (1780 to 1784).

Baquíjano had “sharply criticized the treatment of the natives . . . . Spanish barbarism had brought hunger, desolation, death and other calamities to the Indians . . . the horrors from which the natives suffered (seemed almost to have) justified the recent uprising (referring to that of Tupac Amaru).” Calling on the (no doubt disputed) authority of the French Encyclopaedists and other Enlightenment writers, Baquíjano “informed the Viceroy that it is always prudent for the ruler to remember that the life of each citizen is worthy of respect and that to destroy men within society is not only evil but undermines the efficiency of the body politic . . . Victory of arms do not instill fear. They encourage a spirit of revolution, which will explode on the first propitious occasion[vi].”

Baquíjano had “sharply criticized the treatment of the natives . . . . Spanish barbarism had brought hunger, desolation, death and other calamities to the Indians . . . the horrors from which the natives suffered (seemed almost to have) justified the recent uprising (referring to that of Tupac Amaru).” Calling on the (no doubt disputed) authority of the French Encyclopaedists and other Enlightenment writers, Baquíjano “informed the Viceroy that it is always prudent for the ruler to remember that the life of each citizen is worthy of respect and that to destroy men within society is not only evil but undermines the efficiency of the body politic . . . Victory of arms do not instill fear. They encourage a spirit of revolution, which will explode on the first propitious occasion[vi].”

We suppose that the pole position of the Baquíjano and Carrillo families and the title Conde de Vista Florída saved José from the chopping block[vii] but later in the year his proposed reforms of the San Marcos university curriculum –based, as the old system was, on scholasticism[viii]– were reined in by the conservatives.

The enlightened –one might say the enlightenment – views of Baquíjano over two hundred years ago stand out as robust and unequivocal statements, part of the first cries for liberty from among even the aristocratic elite.

The enlightened –one might say the enlightenment – views of Baquíjano over two hundred years ago stand out as robust and unequivocal statements, part of the first cries for liberty from among even the aristocratic elite.

Why could it be said that José Baquíjano y Carrillo “saved the honor of Peru”? The accusation that historians have thrown at the creole (criollo) leadership of the time (say from the rebellion of Tupac Amaru II in 1780 through to independence) was that they did little themselves to foster Peru´s emancipation from Spanish rule, whilst benefitting from a property, power & ‘knowledge’ take-over from both the Spanish-born peninsulares and the common resources of the campesinos. Among historians it is hotly contested as to whether (a) the Peruvian-born Lima elite (the criollos) either left it to others (foreign Generals San Martín and Bolívar) or just hoped that the whole thing would go away, or (b) there was a more significant Peruvian contribution to independence than in the earlier textbooks. (See article on Emancipation in the Peruvian Times History of Peru series – forthcoming.)

Well, we’ve been day-dreaming long enough and not really paying enough attention to the exhibits or indeed the casa itself, which is a Republican rebuild. The glasswork of the vitrales (etched panes), claraboyas (skylights) and teatinas (dormer-type skylights) literally takes no short-cuts, laboriously sculpting rounded panes for maximum aesthetic effect – or show-off potential depending on your point of view! The “living room” (see photo) now displays some of the best minerals in the collection.

Well, we’ve been day-dreaming long enough and not really paying enough attention to the exhibits or indeed the casa itself, which is a Republican rebuild. The glasswork of the vitrales (etched panes), claraboyas (skylights) and teatinas (dormer-type skylights) literally takes no short-cuts, laboriously sculpting rounded panes for maximum aesthetic effect – or show-off potential depending on your point of view! The “living room” (see photo) now displays some of the best minerals in the collection.

En route to the museum why not wander around the Plaza San Martin, which lies due north from the Estación Central on the Metropolitano. The buildings surrounding the Plaza have been repainted in Castañeda Cream – really off-white – and it looks the better for it. True, there are slight variations: pale white, dark white and so on. Even the base of General San Martín’s equestrian statue has been given the treatment. [Castañeda, of course, refers to ex-mayor Luis Castañeda Lossio, in whose honor there is a plaque on the corner of San Martin and Quilca claiming the work as his own, which prompts the foreign visitor to speculate that it must have taken pretty much all his spare time and more.] On the corner – Quilca with San Martín – is the Teatro Colón (The Columbus/Columbia Theater) also painted white. Next door you can admire the white uniformed livery of the club doormen at the eventual powerhouse of Lima society, the Club Nacional, though they have resisted the painting of the building. The lot next to the Club was the site of another of Lima’s magnificent houses of the caliber of the Casa Belén (torn down so that club members and others could park their cars). Now you have arrived at Jirón de Unión 1030 and if you are a student, a teacher or pensioner you can enter for half the usual price. Take a bunch of six year-olds or under and they will get in for free.

More information

- Official website – www.madc.com.pe

- Open 9am to 6pm Wed-Mon. Closed on official holidays. Museum includes a cafeteria and a museum shop.

- More photos– http://www.fotosdemuseos.com/2011/03/museo-andres-del-castillo.html

- More on Jose Baquijano y Carrillo, Count of Vista Florida (1751-1818)[ix]. Wikipedia article checked for reliability 18 March 2011. Written by the excellent Robert Braunwart, who sadly died of cáncer Oct. 14, 2007. See http://en.wikipedia.org/w

[i] Say “Ho-zay Bucky Harno iiii Carrrr-ill-yo” and you might even get invited to an elite dinner table.

[ii] http://bib.cervantesvirtual.com/servlet/SirveObras/12727219747815940876435/ima0005.htm (click to view facsimilies at the Peruvian National Library – install a CoolPreview reader [http://www.coolpreviews.com/] to see them within this page).

[iii] Over-the-top? Not yet. The building really does inspire. But it is still pristine and could – if not maintained – revert to what it had become a few years ago: a run-down mercadillo, then restaurant in a part of Lima shunned by the chattering classes.

[iv] Otherwise known as Checacupe, Canchis province, Cusco. The brutality of the Spanish repression that followed provided the ambience of fear and shock that must have been present in Lima when Baquíjano delivered his speech.

[v] Pluralistic Independence: that is an Independence which was not purely a creole takeover. Though Pumacahua, Melgar and others did rekindle the dream but much later in 1814.

[vi] Paraphrased from F.B.Pike The Modern History of Peru pages 34-35.

[vii] Though he died – one of the bravest and most illustrious sons of Peru – in a prison in Spain in 1818 just three years short of the Declaration of Independence in 1821.

[viii] Scholasticism was still alive and kicking when this author first put foot onto Latin American soil in 1963.

[ix] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jos%C3%A9_Baqu%C3%ADjano