By Paul Goulder

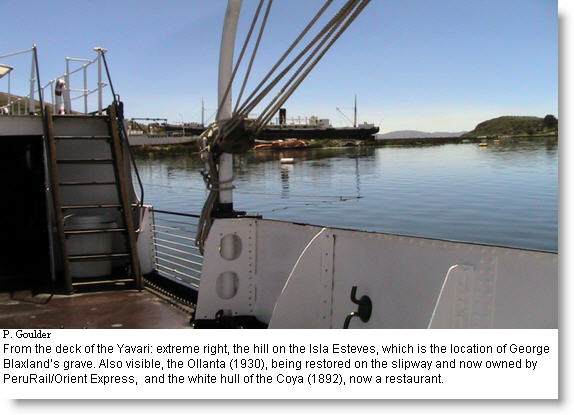

On March 6 Capt. Carlos Saavedra stepped down from his command of the oldest working single-screw iron ship in the world, the Yavari. We might say that she is, together with her sister ship the Yapura (today the Navy’s BAP Puno), not only the oldest but also the “highest” in the world given that their home port is Puno, Lake Titicaca (3,810 meters, or 12,500 ft, above sea level).

Both Saavedra and the Yavari’s conservation project director, Meriel Larken, are fulsome in their praise of the crew and the behind-the-scenes team, including the trustees, who have now achieved what looked almost impossible a couple of decades ago: the restoration of this ship which has major historical significance for Peru. The retirement of Carlos Saavedra, after sixteen years, was also marked by a working voyage for M/N Yavari around Puno Bay.

Those who have experience of ships and restoration projects say that the natural management style and characteristic humour of Saavedra – and the naval ability to work with a team of men (and one or two women) in confined spaces – was the essential complement to the vision, persistence, and international contacts of Meriel Larken. And the retiring commander is the first to maintain that without the dogged determination of the Director nothing would have been achieved – let alone the necessary infusion of an estimated $630,000 on restoration and maintenance.

Those who have experience of ships and restoration projects say that the natural management style and characteristic humour of Saavedra – and the naval ability to work with a team of men (and one or two women) in confined spaces – was the essential complement to the vision, persistence, and international contacts of Meriel Larken. And the retiring commander is the first to maintain that without the dogged determination of the Director nothing would have been achieved – let alone the necessary infusion of an estimated $630,000 on restoration and maintenance.

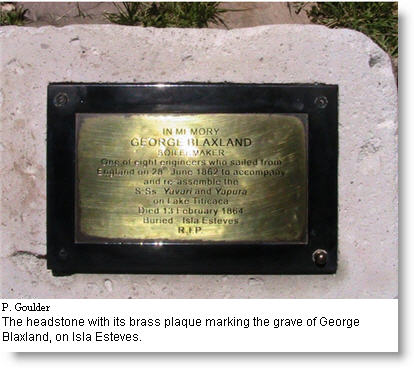

The ceremony was preceded by another, on February 13th 2009. This was a form of requiem memorial service for engineer George Blaxland who died the same day in 1864. His grave, recently rediscovered, lies on the brow of the hill on the Isla Esteves, known to tourists for its swanky Libertador Hotel. It was also a chance to pay tribute to the several Peruvians and British who died on the original project – mainly engineers, muleteers, and navy men.

The plaque records “In memory, George Blaxland, Boilermaker. One of eight engineers who sailed from England on 28th June 1862 to accompany and re-assemble the SS Yavari and SS Yapura on Lake Titicaca. Died 13th February 1864. Buried – Isla Esteves. RIP.” (The “boilermaker”, eight thousand miles from base, is scientist, technician, engineer, inventor, drawer, sketcher, mathematician, conceptualizer, architect, gasfitter. . .)

These ceremonies seem to mark a turning point for the Yavari project and the project’s own website sets out a Stage 2 which could turn out to be just as expensive as the completed restoration. The next stage aims to make the Yavari commercially viable and modernised in terms of safety and sea-worthiness so that passengers may be carried to different destinations and attractions on the Lake.

Moving to the next stage

In moving to the next stage, the Yavari team has one trump card which has not been fully exploited: in the absence of the Huascar, now in “captivity” in Chile, the Yavari (and the Yapura) remain the iconic maritime “museums of the memory” which could yet, still assuage the remorse and bitterness that still lingers following the Chilean occupation of Peru 1880-1884.

As it was put to me on board the Yavari: Ramon Castilla ordered these ships together with the Huascar (being built in Birkenhead by Laird Bros, launched October 7, 1865 – whilst the Yavari was being assembled in Puno) partly in the hope of keeping the then maritime power (the British Navy) on-side, or at least as a neutral Pacific police force.

What happened, in fact, sometime between 1870 and 1879, was that a de facto pact with Britain was sacrificed for a de jure alliance with Bolivia. Not only was Bolivia not able to deliver, it tied Peru into a disastrous and hopeless defence of the area which had once been Upper Peru but which still, then, had an ample but undefended coastline.

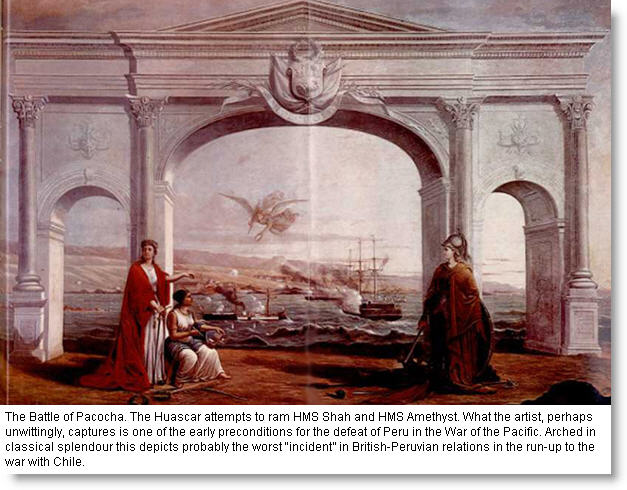

The failure of diplomacy and the instability of the regimes post-Castilla reached a low point in 1877 when the Government of Mariano Prado lost control of the SS Huascar to a rebel-group lead by future President Pierola, and the famous iron turret-ship found itself in a sea battle with two British Navy ships (The Pacocha incident, May 22). Castilla would have now been turning in his grave (d.May 25, 1867). And Pierola had, it could be argued, sealed the fate of Peru in the forthcoming war with Chile two years before the conflict started.

The significance of the ships for Peru

The ships (Yavari and Yapura) were part of a “strategic plan” by Ramon Castilla, generally considered to have been one of Peru’s greatest presidents – certainly one of the most adventurous as a military and political campaigner. Following the defeat of Peru by Bolivia (Battle of Ingavi 1841), the defence of Peru and the integrity of its borders was no doubt uppermost in Castilla’s mind but two other objectives were also vital: the construction of a unified nation from various caudillo(warlord)-dominated parts, and the modernisation of the country. The Yavari / Yapura twins fitted the bill precisely. They were to provide Peruvian hegemony over Lake Titicaca, show the Peruvian state flag in independently-minded Puno and disseminate state-of-the-art steam technology to aspiring young Puneños. Ship-building equals nation-building, QED.

The significance of the ships for Puno

The battle of Ingave had exposed the weak position of Peru in its inability to defend the strategic transcontinental corridor which was and is located between Lake Titicaca and the Salt Flats to the south. For millennia the natural trade, mining and arriero routes had converged on the area between the middle horizon capital Tiwanaku and the Colla heartland near Lampa.

The city of Puno was and is central to this area. Today in the small town of Moho, further round the lake, they celebrate the eternal tension between Inca, Colla, Collagua and Uros with mock battles in the town square on February 5 each year. Puno and its commercial sister, Juliaca, continue to be undervalued. In turn, Puno still doesn’t quite see the point of the Yavari (or indeed of the Inca which was dispatched to the breakers) – perhaps because no shot was ever fired in anger. Wake up Puno, you have in the Yavari, thanks to the conservation project, to Ramon Castilla and to Chilean misunderstanding of Peruvian sensibilities over the SS Huascar, a “cast-iron case” for an uncontroversial “museum of the memory”. All the better that it should be mobile and offer tourists a run for their money.

The Peruvian Times wishes every success both to Carlos Saavedra and to the Yavari as they set new courses in the weeks and months ahead.

Note. Readers who would like to know more about Ramon Castilla – Peru’s Lincoln – can consult the Castilla videos made by historian Antonio Zapata for PeruTV. Google “Sucedio en el Peru, youtube – Castilla”. If you are new to Peru, this is a series you should not miss!

An academic version (extended with footnotes and references) of this article will be available in the Opentext Journal of Peruvian Studies (Google “Minkapedia”) or direct from the author. Details of the Yavari project can be found at http://www.yavari.org/