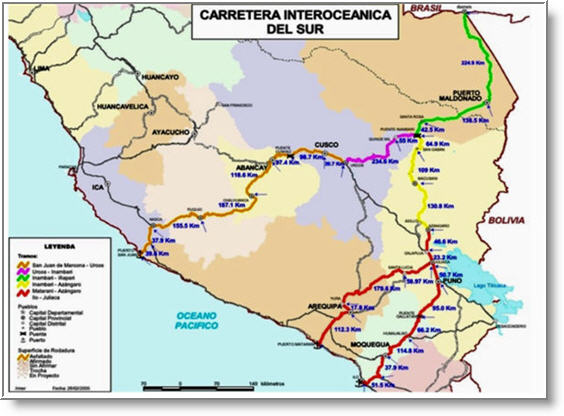

For decades a road linking the Amazon heartlands to the Pacific Ocean was on the drawing board. It is now a reality with the opening of the Interoceanic Highway connecting southern Peru and its ports to the Brazilian states of Rondonia, Acre and beyond. Will this open up the rainforest to extensive soya bean farming and cattle ranching to supply Far Eastern markets or will it bring a range of economic and social benefits for the local people?

In November 2012, British author and filmmaker Tony Morrison, and John Forrest, chairman of the Tambopata Reserve Society, gave the Anglo Peruvian Society in London an account of the InterOceanic Highway after its first year of completion. The following are the main points of their presentation. In 2012, John travelled the lesser known ‘Route 4’ link which runs from Juliaca to Puerto Maldonado where Tony, who was travelling along the Highway in October that same year, took up the narrative into Brazil.

John opened the evening by looking back to the 1960s, to the birth of the road plan. Peru’s President Fernando Belaunde [1963 -1968 and a second term 1980 – 1985], was by training an architect and a politician who pushed for road building to integrate distant parts of the country. Belaunde began the construction of the Marginal Highway [Carretera Marginal de la Selva] a route along the forested eastern flank of the Andes mountains that joined existing trans-Andean roads crossing to the Pacific. Another Belaunde plan was to link Peru with the Brasilian road system then being developed in the Amazon.

John opened the evening by looking back to the 1960s, to the birth of the road plan. Peru’s President Fernando Belaunde [1963 -1968 and a second term 1980 – 1985], was by training an architect and a politician who pushed for road building to integrate distant parts of the country. Belaunde began the construction of the Marginal Highway [Carretera Marginal de la Selva] a route along the forested eastern flank of the Andes mountains that joined existing trans-Andean roads crossing to the Pacific. Another Belaunde plan was to link Peru with the Brasilian road system then being developed in the Amazon.

Even more ambitiously, Belaunde had a grandiose plan to move the Peruvian seat of government from Lima to the Amazon. Some would say his plan was simply a dream based on the creation of the new Brazilian capital, Brasilia [built 1957- 61], and sited in the center rather than on the coast. In the case of Peru, almost sixty percent can be called Amazon land and most of it is sparsely populated — for Belaunde it was a region to be opened-up and used.

The newly completed InterOceanica Sur road linking the Pacific ports of Ilo, Matarani [see Islay near Mollendo] and San Juan de Marcona on the Peruvian coast is a marvel of planning and construction A consortium of Peruvian and Brazilian companies led by the giant Odebrecht and Camargo Correa were responsible for the work financed in the order of US$1.9 billion by international development banks. The work was divided between the companies, with each working on different sectors or tramos.

Looking eastward towards the Amazon forest, two routes lead over the mountains

Tramo 4 from the mountain town of Azangaro, 27 km almost due north from Lake Titicaca, has a highest point of 4725m, and Tramo 2 from Urcos near Cusco, famed for its Inca remains, reaches 4850m. Both roads lead down the eastern Andean slopes through dense mountain rainforest recognised worldwide for its rich and probably unparalleled biodiversity. The routes join at Puente Inambari in the foothills 375 m above sea level, and continue for another 179 km to Puerto Maldonado, a town of about 92,000 [2005] and the capital of the Madre de Dios Region.

Tramo 4 from the mountain town of Azangaro, 27 km almost due north from Lake Titicaca, has a highest point of 4725m, and Tramo 2 from Urcos near Cusco, famed for its Inca remains, reaches 4850m. Both roads lead down the eastern Andean slopes through dense mountain rainforest recognised worldwide for its rich and probably unparalleled biodiversity. The routes join at Puente Inambari in the foothills 375 m above sea level, and continue for another 179 km to Puerto Maldonado, a town of about 92,000 [2005] and the capital of the Madre de Dios Region.

Puerto Maldonado has been connected by road to the highlands for many years but a journey from Cusco was usually counted in days. In the rainy season it could take a couple of weeks and sometimes the route was totally impassable.

Now there are at least two bus services per day and direct buses from Lima and Sao Paulo. Inevitably, migrants are heading to Puerto Maldonado and towns along the road where they settle and work. One estimate says that there are 200 new arrivals per day.

Farming along the roadside is still modest, with families clearing the forest and planting crops such as yuca [manioc/cassava]. The chacras or cleared patches are clearly visible on satellite images.

Of major concern is the unregulated gold mining in the lowland forest east of Cusco. The area has always attracted gold seekers and groups of men eagerly wash for gold along the riverbanks while others seek deposits under the earth. One of the most notorious sites is Huaypetue, in  foothills about 2km east of the road near Santa Rosa. Huaypetue reached its peak in the early 1990s and now the prospectors are looking elsewhere.

foothills about 2km east of the road near Santa Rosa. Huaypetue reached its peak in the early 1990s and now the prospectors are looking elsewhere.

The men earn several dollars a day and it has been estimated that the annual production is about 30 tonnes of gold. To separate that gold about 30 tonnes of mercury and other chemicals are used. Environmentally, it is a high price as the mercury and its residue ends up in the rivers.

At the beginning of 2012, the Government imposed controls and miners are expected to register and work within a 500,000 hectare corridor bordering the river.

Clearly Puerto Maldonado is growing, though exact population figures are not available – the 2005 census counted 92,000 and by some estimates that has doubled.

Clearly Puerto Maldonado is growing, though exact population figures are not available – the 2005 census counted 92,000 and by some estimates that has doubled.

Serious attempts to attract tourists began in the late 1970s and it is now a popular destination for eco-tourists from around the world. The Tambopata river has more than a dozen ‘lodges’ — rustic hotels— and on most days two flights arrive from Lima via Cusco. All of the lodges provide tourists with a canoe journey on the Tambopata river and a night in the jungle. But some do more, with specialist guides for bird spotting or closer to forest living —the Baltimore Project for Rural Tourism, for instance, offers accommodation with families settled in the forest.

Fortunately large areas have been given some protection. The world famous Manu National Park and World Heritage Area includes some headwaters of the Madre de Dios river. The Bahuaja Sonene National Park running next to the Tambopata National Reserve, the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve for indigenous communities and the Alto Purus National Park embracing the headwaters of the Purus river, a major Amazon tributary. MAP? If you have one.

This is how the limits are set out today but past experience reveals that the boundaries can be moved if deemed in the National interest. This was done in 2007 when the area of the Bahuaja Sonene was reduced by a third to permit future gas and oil exploration.

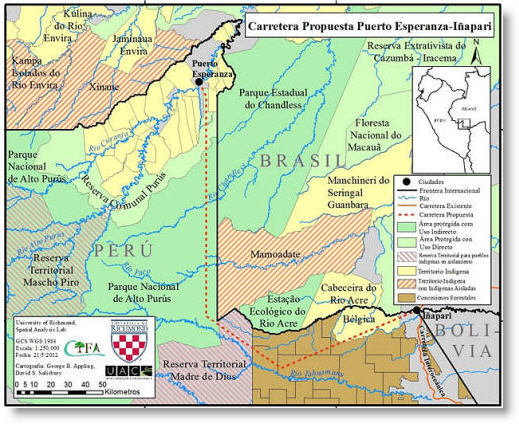

The forests of the Alto Purus are almost pristine and the only significant settlement is Puerto Esperanza with about 4000 inhabitants. There is a move among the population to get a road built connecting with Inapari, the frontier town. This proposal has opponents as the forest close to the Brazilian border is home to an unknown number of indigenous families.

The forests of the Alto Purus are almost pristine and the only significant settlement is Puerto Esperanza with about 4000 inhabitants. There is a move among the population to get a road built connecting with Inapari, the frontier town. This proposal has opponents as the forest close to the Brazilian border is home to an unknown number of indigenous families.

The people and their simple forest homes have been filmed from the air but so far no contact has been made on the ground. Other tribes live in the forest between the Alto Purus and Rio Las Piedras and they made news earlier this year when they were seen by tourists.

In Puerto Maldonado the road is now a fact and the bridge has been open to traffic for over a year. For the townspeople its presence is inescapable as the access roads with massive concrete barriers dominate the center of town. [Such planning would be impossible in Britain.]

In Puerto Maldonado the road is now a fact and the bridge has been open to traffic for over a year. For the townspeople its presence is inescapable as the access roads with massive concrete barriers dominate the center of town. [Such planning would be impossible in Britain.]

At this point, Tony Morrison continued….

The bridge has a fascinating story. In southern Peru, the Puente Continental, with a span of 528m and 2,800 tonnes, is the longest bridge in Peru and the longest suspension bridge ever constructed by the Austrian engineering company, Waagner-Biro. It was ordered back in the late 1970s and when the parts arrived, a shortage of cash and the lack of infrastructure, such as a road, left the parts sitting idle in a warehouse for about 25 years. All that changed with the Peruvian-Brazilian accord to fulfill the long cherished dream of an inter oceanic route.

The bridge has a fascinating story. In southern Peru, the Puente Continental, with a span of 528m and 2,800 tonnes, is the longest bridge in Peru and the longest suspension bridge ever constructed by the Austrian engineering company, Waagner-Biro. It was ordered back in the late 1970s and when the parts arrived, a shortage of cash and the lack of infrastructure, such as a road, left the parts sitting idle in a warehouse for about 25 years. All that changed with the Peruvian-Brazilian accord to fulfill the long cherished dream of an inter oceanic route.

It is hard to imagine that this huge river —it rises by at least ten meters in the rainy season— is not navigable all the way to the Amazon. But on the way it joins two major rivers. The Beni comes in from Bolivia —one of its tributaries is that polluted trickle that runs through La Paz— and another is the Mamoré coming in from southern Bolivia with tributaries such as the Pirai, the river of Santa Cruz – and these with many other finally become the Madeira, the Amazon’s great tributary. This huge river then pours over a series of giant rapids which to date have blocked the way to upstream navigation.

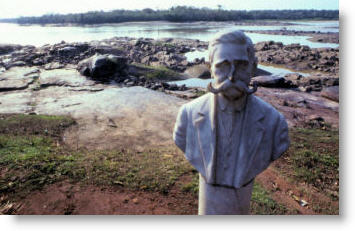

The road north from the Madre de Dios crosses one famous river – the Tahuamanú. In fact, the town here, Iberia, was once called Tahuamanú. Its history is tied to the late 19th century and the  story of rubber, when the near feudal control of the area was making fortunes for absentee landlords . Some of you may recall the film and book Lizzie I created for the BBC in 1985. Lizzie, a young Victorian lady, spent the final days of her short life on a rubber barraca, a collecting point downriver from this point.

story of rubber, when the near feudal control of the area was making fortunes for absentee landlords . Some of you may recall the film and book Lizzie I created for the BBC in 1985. Lizzie, a young Victorian lady, spent the final days of her short life on a rubber barraca, a collecting point downriver from this point.

The Tahuamanú, photographed here from the bridge near Iberia, eventually leads to the Amazon via the river Beni and the rapids.

At the border, the road crosses the Acre river – also with a great rubber era history – but unlike the Tahuamanú with its route to the Amazon blocked by rapids, the Acre river flows to the Purus. It is shallow and without rapids. In high water the Purus is navigable for 2600 kms to the main Amazon —no wonder that in the Rubber Era small ocean-going steamers were seen not far from here.

And before leaving the border, there is a final curiosity – the settlement of Bolpebra in Bolivia — just 1500 m from the Aduana (Customs) Post . It’s the place where Bolivia, Peru and Brazil meet — it’s a fairly fluid frontier, you could say.

But now looking at the future use of the InterOceanica, maybe a few tips can be gleaned from the history of the rubber era, as the size of the profit from rubber trees depended largely on the cost of transportation. Tahuamanu rubber had to go out via the rapids, and that problem in turn spawned a couple of railways and one immense fortune —Nicolás Suarez, a Bolivian, was so powerful that he ran his own private army. I mention all this because in Amazonia today the cost of transportation is all-important. Remember, Amazonia is much the same size as the continental USA.

But now looking at the future use of the InterOceanica, maybe a few tips can be gleaned from the history of the rubber era, as the size of the profit from rubber trees depended largely on the cost of transportation. Tahuamanu rubber had to go out via the rapids, and that problem in turn spawned a couple of railways and one immense fortune —Nicolás Suarez, a Bolivian, was so powerful that he ran his own private army. I mention all this because in Amazonia today the cost of transportation is all-important. Remember, Amazonia is much the same size as the continental USA.

In the past five years I have made five long bus journeys across Amazonia —choosing a comfortable bus instead of a canoe or hacking through forest, as I did in the past. Perhaps a comfortable bus reflects my status as a Senior Citizen and also reflects a changing Amazonia, one in which good bus travel is possible and the penetration of the original wilderness from every direction is going ahead at a remarkable pace.

After my first bus journeys I sensed that my wife Marion —who has fond memories of mosquitoes and canoe travel— didn’t believe me. But recently she has joined me and seen what I am calling the New Amazonia, as —indeed— it is very much part of modern Brazil. By New Amazonia I do not mean that all the forests have gone —AND I’m not going to join in with the haggling over percentages being cut or still standing, or the concern over carbon dioxide and climate change or the controversy over the use of Amazonia as a resource —that is for others and another time.

Here, I will mention just a few places and a couple of pictures so that you can see how towns and cities are big. And growing quickly.

Porto Velho has a new bridge across the River Madeira.

Manaus, once thought of as the center of the Amazon, now has 2 million people, and a special incentive industrial zone turning out hundreds of goods ranging from smartfones to motorcycles. AND a new bridge 3595 km long built across the Rio Negro —started in 2007— opened last year.

Belem, the great port near the Amazon mouth –its metropolitan area adds up to 2.5 million.

Cuiabá, on a river draining to the Plate system, is the gateway to the Mato Grosso – another 2 million. In 1950, the population was just 62,000.

My list could be endless so I’ll stop here. So what brings people into Amazonia ? Farming, small industries and minerals. And the products? How do they export them? Soybean is the most talked about as it is sold internationally, with 29 million metric tonnes going from Brasil to Asia in 2010. Mato Grosso was the major producer.

So back to the InterOceanica, and the theoretical export route from Amazonia via Peru’s Pacific ports. It is my belief that the cost per ton is too high, as even in 40-ton trucks there is the extra cost of fuel to climb over the Andes mountain ranges.

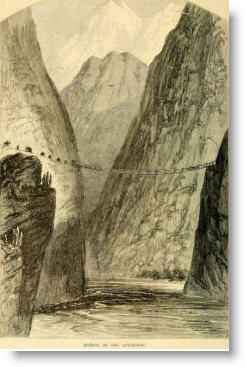

Just take the northern route over the 4,750 Pass of Pirhuayan and down to Urcos near Cusco. To get to the coast it is not downhill all the way and there are formidable barriers to cross. One of the obstacles is the canyon of the Apurimac river coming from the Amazon’s source. The canyon is over 2000m deep and the road goes down to the river and then out again with a series of hair-raising bends.

Just take the northern route over the 4,750 Pass of Pirhuayan and down to Urcos near Cusco. To get to the coast it is not downhill all the way and there are formidable barriers to cross. One of the obstacles is the canyon of the Apurimac river coming from the Amazon’s source. The canyon is over 2000m deep and the road goes down to the river and then out again with a series of hair-raising bends.

Beyond are the heights of Yaurihuiri, at over 4300 m, that together with shorter climbs along the way add up to over 9600 m of uphill driving, or about 800 m more than an ascent of Everest [8,848].

Can you imagine a line of about 1500 trucks grinding uphill in low gear and then through snow covered passes? About 1500 trucks would be required to carry the same as a Panamax grain carrier ship [Panamax = the size of vessel able to pass through the current Panama canal].

The southern route leading to Ilo and Matarani has to climb to the Abra Oquepuno at 4850 m, which is 40 m higher than Mont Blanc, Europe’s highest mountain, and then after a short descent the road has to climb another 700+ m before eventually heading downhill to the Pacific. As far as I can see, the total uphill driving from the eastern Andean foothills on this route would be over 5300 m.

Can you imagine the 2011 Rondonia production alone of 446,000 metric tonnes of soya being taken to the top of Mount Everest and then down again before being shipped? That would be crazy, not just from the dollar cost but the pointless cost in energy. Acre, the state with the best connection to the Interoceanica, is not yet a major producer of soya. Among the State’s production are brazil nuts, natural oils and latex – used for condoms made in a factory in Xapuri. You can see how the figures for long-haul road transport do not add up commercially. In the adjacent state of Mato Grosso the soya harvest in 2011 was 22 million metric tonnes. The US Department of Agriculture monitoring world prices for soya noted the rising cost of truck transport to get the soya to river ports – this rise was in part due to recently imposed Brazilian restrictions on driving hours.

For most bulk transport the Amazon river provides low cost shipping to all parts of the world, including Asia. From the Amazon port of Santarem – that’s where UK television traveler Michael Palin began his journey to see Henry Ford’s old plantations in Fordlandia – from Santarém and from Manaus 2,300,000 metric tons of soybean were exported last year.

For most bulk transport the Amazon river provides low cost shipping to all parts of the world, including Asia. From the Amazon port of Santarem – that’s where UK television traveler Michael Palin began his journey to see Henry Ford’s old plantations in Fordlandia – from Santarém and from Manaus 2,300,000 metric tons of soybean were exported last year.

When talking of figures for Manaus, that usually means from the grain port of Itacoatiara on the Amazon’s northern bank, some 200 km downstream from Manaus. Itacoatiara is virtually opposite the mouth of the Madeira and ideally placed to receive barge traffic from Rondonia.

So the Brazilian answer to soybean transport is to use trucks to get the soybeans to silos and then to barges along the rivers or on lakes now filling behind the huge dams being built for power.

As an aside, I should mention that one proposal by an American ’think tank’ of the late 1960s suggested creating a series of Great Lakes in Amazonia The idea was reported widely and in 1967 The Times, London, carried almost a full page story and map.

The plan suggested that a series of dams not exceeding 33m high could be built across some rivers and create lakes, allowing shipping between ports on the surrounding shores. With transport in place it would become easier to extract timber or minerals and permit the production of energy.

The plan suggested that a series of dams not exceeding 33m high could be built across some rivers and create lakes, allowing shipping between ports on the surrounding shores. With transport in place it would become easier to extract timber or minerals and permit the production of energy.

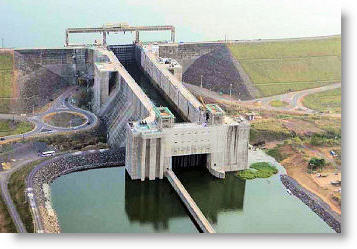

For years the idea was viewed with alarm as a nightmare. But now in 2011 rivers, dams and man-made lakes are part of the planning to permit low cost transportation of the immense amounts of Amazonian agricultural produce, minerals and timber. On the western side of Amazonia, close to Interoceanica connections, a series of dams has been planned to open the route along the Rio Madeira to the Amazon — two of the dams are almost complete and will have ship-locks. Both are being built on rapids that were previously major obstacles to navigation.

The Santo Antonio dam near Porto Velho, 3,100 m long and 13.4 m high will generate 3,140MW when it is fully on stream in 2016. Much of that energy will be ‘exported’ to southeast Brazil.

The Girau dam about 120 km upstream from Porto Velho, also due to be fully generating by 2016, is 1150 m wide and 62 m high. These are truly staggering projects and, if the four dams are completed, will change this corner of Amazonia forever. Just over 4000 km of waterway will be opened for navigation and, by one estimate, as much as 143,000 hectares of land in western Amazonia will be opened for soybean planting – assuming of course that all the soil is suitable.

To give you some idea of the scale and intention

Here’s one set of locks at Tucuruí, on the Tocantins river over in eastern Amazonia where the system is working already. Two sets of locks give a lift of 75 metres and the contruction’s total is more than the height of London’s Big Ben clock tower – you can even drive under the main lock. A six kilometer canal has been cut to join sets of two locks and avoid rapids. By using barges, any bulk products from Madre de Dios Region could be exported at

Here’s one set of locks at Tucuruí, on the Tocantins river over in eastern Amazonia where the system is working already. Two sets of locks give a lift of 75 metres and the contruction’s total is more than the height of London’s Big Ben clock tower – you can even drive under the main lock. A six kilometer canal has been cut to join sets of two locks and avoid rapids. By using barges, any bulk products from Madre de Dios Region could be exported at  low cost via the Amazon — much as rubber was in the 19th century. Of course, the other two dams would be essential for simplifying the route —but money for products and money for infrastructure seem to go hand in hand – at least in Brazil.

low cost via the Amazon — much as rubber was in the 19th century. Of course, the other two dams would be essential for simplifying the route —but money for products and money for infrastructure seem to go hand in hand – at least in Brazil.

And finally to the thorny topic of further road building in Madre de Dios and the adjacent province of Purus.

There are suggestions that a road could be built from Iñapari to Puerto Esperanza on the Purus. [See map above.] Not everyone is against the idea, but objections include the danger to the Purus National Park and contiguous reserves. The area is largely pristine tropical forest and home to small pockets of forest tribal people — perhaps numbering no more than a couple of hundred, who have had no real contact with Europeans since the rubber era.

A road here would introduce more people and machinery.

I feel this is a good place to finish, as a new road would certainly improve the life of the existing settlers and open up the area. In the short term it could provide a way to take forest products to the navigable Purus.

And the Government is not entirely against the road, so with economics and the need to establish a stronger Peruvian presence in Purus on its side of the border, it could get a go ahead.

Looking to what may happen in this part of Amazonia is crystal ball gazing territory

At present, about 18.4 percent of the Madre de Dios Region is devoted to parks and reserves —and how the remainder of the land is used will depend on how well it is suited to crops. In the short term, small scale farming and extraction of forest products will enjoy easy transport along the new highway. But any large scale agricultural production requiring major investment would look very carefully at transport costs.

The first steps will be logging and already trucks are seen every day —even back in the 1960s when we were there, timber from Quincemil was hauled over the mountains . I can recall riding uphill on a pile of lumber and chatting about a forest people —the Huachipari— with an American anthropologist. The timber was bound for Cusco.

But once the waterways or hidrovías are completed, the export route will be via the Amazon. In high water season the Purus river offers an easy route —it is long and very meandering so it is not good year-round but soybean is harvested usually in March, a high water season for the rivers.

So more people – more roads – more regional prosperity add up to a good reason to rigorously protect the likes of Tambopata, Manu and Bahuaja-Sonene.

The Interoceanica road itself will almost certainly act as a conduit to bring settlers from the impoverished highlands – you can see that in the case of Pucallpa: a road of sorts was built in 1945 and the population is now 200,000. And in Bolivia, Santa Cruz de la Sierra was a small town of about 50,000 in 1950, and with a road built in the 1950s it has grown to 2 million —it is now the largest city in Bolivia.

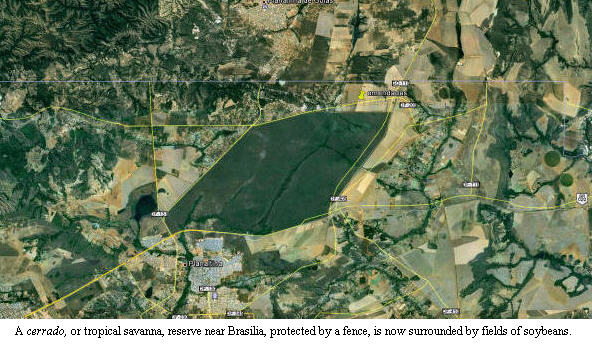

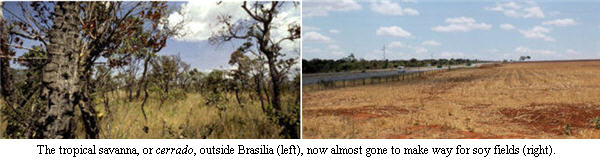

It is with apologies to the Society that I will finish near Brasilia, the capital built from scratch in the cerrado, or tropical savanna, in the late 1950’s. Perhaps we should not forget that President Belaunde also had a plan to move the Peruvian capital from Lima to the rainforest – it was named Ciudad Constitución, but it never really got of the ground. Yet the rough roads connecting the site to other parts of Peru are in place.

Now back to Brasilia – in 1977, I was helping the producers of a David Attenborough Life on Earth film and was taken to a small reserve about 35 km outside the city. From this particular spot streams beginning underground flow south to the Plate system and Buenos Aires or north to the Amazon and Belem.

A month ago, I was there again to see how, apart from the reserve, the cerrado had gone. The reserve is well protected and surrounded by a fence. Outside the fence and, huge soya fields sit cheek by jowl with the wilderness, still home to the wildlife as we filmed it just less than forty years ago. Two towns and a major highway abut the reserve.

Man is truly taking over the planet.

All photos: South American Pictures and NonesuchExpeditions

Tony Morrison’s stunning, eye-popping description here of how, today, the Western Amazon is being swiftly transformed by huge dams and roads is of extraordinary importance, not just to Peru but to the world.

Less than half a century ago the Amazon was still always described as ‘impenetrable’. Tony Morrison shows here how this has not only changed but warns that it will be changing even faster over the coming few years.

N.B. Note his calculation that trucks coming from Brazil over the TrnasOceanica have to grind up and down the height equivalent of going over Mount Everest!

Good read by an observer with boots on the ground. Morrison underscores that Amazonia is now urbanized (80% of the population lives in cities) with an emerging transport and energy infrastructure. I am not persuaded, however, that the interoceanic highways are going to become a major route for international trade. So-called Amazonia is at least two different biomes. Agricultural development is in the cerrado (savannah) and there is no agronomic evidence to support the idea that soybeans and cattle are going to spread on a large scale into the Amazonian tropical rainforest biome. Bulk cargoes from the cerrado are going to move eastward to ports like Santarem, Belem and Sao Luiz (Maranhao) at much lower transportation costs than moving over the Andes. The transcontinental highways to the Pacific are having important local effects, but they are not going to be competetive with the eastern river routes. This could change if major mining and oil/gas discoveries are made on the Andean eastern slopes, but that is not yet the case.

(Juan de Onis lives in Sao Paulo and writes for Foreign Affairs. He was for many years the chief correspondent in Latin America for The New York Times.)