By Paul Goulder —

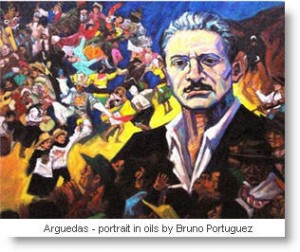

Peru is currently celebrating the centenary of the birth of educator, poet, anthropologist, writer, ethnologist, linguist, novelist and musicologist José María Arguedas. Putting aside the immediate problems that foreigners have with the name (can a bloke be called Maria / where do I find acute accents on the keyboard, etc.), visitors could be forgiven if they don’t quite understand what all the fuss is about – that is, if they are even aware in the first place that there is a lot of fuss and bother going on (you won’t catch much of it on the CNN and BBC channels).

José María or “JMA” as José María Arguedas is frequently and affectionately called, is Peru’s most beloved author especially amongst the millions (two-thirds of Peru) who come from a Quechua-speaking background and from the Andes.

José María or “JMA” as José María Arguedas is frequently and affectionately called, is Peru’s most beloved author especially amongst the millions (two-thirds of Peru) who come from a Quechua-speaking background and from the Andes.

The Minister of Culture, Oxford-trained anthropologist Juan Ossio, has been chasing his tail during the critical days of the anniversary going from one Arguedian event to another. On the JMA birth-day itself, January 18th, he was in Arguedas-associated Puquio (Ayacucho) then back in time for a session dedicated to the post-indigenista author in the Congress and in which most known Arguedianists who happened to be in Lima seemed to be present, then on to a piece of theatre inspired by the life of Arguedas and performed by drama students from the Católica university (in front of San Marcos university – what cheek) and directed by Ana Correa from the theatre group Yuyachkani.

The Minister subsequently reappeared in the sacred cloisters of La Casona of San Marcos university to open “Arguedas and Folk Art” from the Alicia and Celia Bustamante collection and to preside over another performance by a group of Scissor Dancers.

Juan Ossio is planning Arguedian events for the whole year. By contrast historically, January 18 has always been remembered as the date Pizarro founded the Spanish city of Lima. Given also that Pizarro’s equestrian statue was removed not so many years ago from the main square, the Plaza de Armas, this represents a significant shift in emphasis – which may of course be partly nominal, government posturing – away from the Hispanic roots of the traditional Lima elites to the Andean roots of the majority of the population. In 1900, seventy percent of Peruvians spoke variants of Quechua.

We wondered what Arguedas himself would have made of all this! But we also thought that he and our readers from the US and Europe and other Anglophone corners of the world might like to know something of his legacy outside Peru (Arguedas died December 2, 1969), so we set up a conversatorio between Arguedas – or his spirit in the hereafter – and Filomena Sanchez, who was a leading light in the mid 1990s of the Arguedian post-graduate university project called Universidad Internacional Andina. Also present was this reporter from the Peruvian Times (PT) who introduced the conversatorio.

PT – Clint Eastwood’s new film called in English “Hereafter” (Más allá de la vida) has now been premiered on the bamba circuit. Just in time for this session, it “spills the beans” as to how we are able to communicate with you, Dr. Arguedas.

On the theme of the film, the other night they showed the second of the new “Sucedió en el Perú” productions (TV Peru) on the topic of your biography. You may be, or might have been, able to recognize some of it! (laughter) That, of course, was only one event in a continuing series of celebrations and commemorations.

JMA – I’ll come to what they and others have done to my biography in a moment. My first reaction to this whole sequence of events is surprise that a Ministry of Culture has hijacked the affair. They should be doing this in tandem with the Ministry of Education – although I hope the people there have got some tricks up their sleeve for this year. I was, of course, also an educator both in secondary school, in the universities and in the museums. I found it absurd – well, inappropriate given that so much remains to be done – that some should want to name 2011 in honor of me, but it was equally absurd that it should be named in honor of Peruvian submarines or the discovery of Machu Picchu – given the fuss over the Inca artifacts that were taken to the US in 1911 on loan and not returned. Dishonorable deeds need not be commemorated. And Markham had “discovered” Machu Picchu years earlier, as had the land-owners and the local priest and a German explorer and . . .

JMA – I’ll come to what they and others have done to my biography in a moment. My first reaction to this whole sequence of events is surprise that a Ministry of Culture has hijacked the affair. They should be doing this in tandem with the Ministry of Education – although I hope the people there have got some tricks up their sleeve for this year. I was, of course, also an educator both in secondary school, in the universities and in the museums. I found it absurd – well, inappropriate given that so much remains to be done – that some should want to name 2011 in honor of me, but it was equally absurd that it should be named in honor of Peruvian submarines or the discovery of Machu Picchu – given the fuss over the Inca artifacts that were taken to the US in 1911 on loan and not returned. Dishonorable deeds need not be commemorated. And Markham had “discovered” Machu Picchu years earlier, as had the land-owners and the local priest and a German explorer and . . .

PT – We also have with us Filomena Sanchez[ii] who I believe, José María, you knew as a small girl. You called her affectionately Niñacha. She now runs an informal pro-Arguedas, pro-Peruvian cultural organization from her office in London, where she has been living since 1977. She returned to Peru in 1995 with sufficient financial and academic guarantees to propose a research university in your memory – a project that may yet come to fruition given that Congress has passed the enabling legislation. Perhaps, Filomena, you could outline for us how the inspiration of Arguedas came to be felt in Britain. At this point I shall sit to one side and allow the conversation to continue between yourselves.

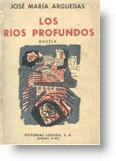

FS – José María used to come round to my uncle’s house in Sucre and join in – singing huaynos alongside my cousin and a friend who played the violin. I did not know who JMA was – who you were (turning to Arguedas) – at the time: we knew you as Gringo but you spoke Quechua and loved being in our company. Later in London, on reading a copy of Rios Profundos, I realized for the first time who that gringo must have been! I had the good fortune to study for a B.A. or licenciatura at London University. The professor who ran the course had introduced Arguedian studies to Britain – and in so doing created Latin American cultural studies with, so to say, an English accent. One of your great achievements in the academic realm was that of approaching subjects from the disciplines of both anthropology and of literature – of really creating Peruvian cultural studies as a discipline.

FS – José María used to come round to my uncle’s house in Sucre and join in – singing huaynos alongside my cousin and a friend who played the violin. I did not know who JMA was – who you were (turning to Arguedas) – at the time: we knew you as Gringo but you spoke Quechua and loved being in our company. Later in London, on reading a copy of Rios Profundos, I realized for the first time who that gringo must have been! I had the good fortune to study for a B.A. or licenciatura at London University. The professor who ran the course had introduced Arguedian studies to Britain – and in so doing created Latin American cultural studies with, so to say, an English accent. One of your great achievements in the academic realm was that of approaching subjects from the disciplines of both anthropology and of literature – of really creating Peruvian cultural studies as a discipline.

JMA – Using literature and anthropology in a way together, or perhaps embedding the anthropology in the literature, was essential to this work of explaining, describing and analyzing one culture, that of the Andes, and presenting it to another, that of the coast. But I am listening intently, fascinated by the story of how my work came to reach the shores of England and of a project for a new type of university. I of course have been, as it were, out of circulation for forty years! I know that from 1958 when I published Rios Profundos, my books were being read, later in translation, abroad. I think that I was too depressed at the time to believe that my work would have much reach outside Peru, let alone England which I never visited. But do carry on, as I am naturally most interested in what has happened to the “Arguedian approach” as it developed after my suicide . . .

FS – Can I ask you if, in literary terms, you felt that you were “successful”? Many regret that you were a one-off, to put it rather brusquely, and they thought that you should have been followed by others who were also Quechua speakers . . .

JMA (interrupting) – Let’s leave the post-mortem till later. Tell me about how my work came to be read in English. What about the United States?

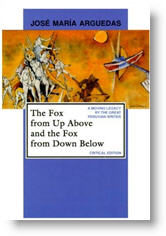

FS – When I was living in California, Pepe Durand, then professor of literature at Berkeley, came round for dinner. It was 1987, and on television in the next room we heard García’s first government was trying to nationalize the banks and Vargas Llosa was leading the opposition in the streets. From Vargas Llosa the conversation jumped to your work. Durand’s students had to read in addition to Rios Profundos (Deep Rivers), El Zorro de Arriba y el Zorro de Abajo (The Fox from up Above and the Fox from Down Below), La Agonía de Rasu Ñiti (The Agony of Rasu Ñiti), and options for others. On the strength of reading you, several went on to do doctorates and became Arguedianist teachers. On the East Coast, Antonio Cornejo Polar taught a whole generation who became researchers, writers, academics, etc who to an extent were carrying the Arguedian flame forwards. Some of them formed an international organization called Jalla, which meets regularly. The overall themes are wider than Andean literature. According to an international book catalogue on internet called WorldCat, there are now 1156 books and thesis under the entry josé María Arguedas. About 15 years ago a group of academics and writers, mostly with Peruvian roots, founded Ciberayllu – loosely an Internet community in the field of Andean literature.

FS – When I was living in California, Pepe Durand, then professor of literature at Berkeley, came round for dinner. It was 1987, and on television in the next room we heard García’s first government was trying to nationalize the banks and Vargas Llosa was leading the opposition in the streets. From Vargas Llosa the conversation jumped to your work. Durand’s students had to read in addition to Rios Profundos (Deep Rivers), El Zorro de Arriba y el Zorro de Abajo (The Fox from up Above and the Fox from Down Below), La Agonía de Rasu Ñiti (The Agony of Rasu Ñiti), and options for others. On the strength of reading you, several went on to do doctorates and became Arguedianist teachers. On the East Coast, Antonio Cornejo Polar taught a whole generation who became researchers, writers, academics, etc who to an extent were carrying the Arguedian flame forwards. Some of them formed an international organization called Jalla, which meets regularly. The overall themes are wider than Andean literature. According to an international book catalogue on internet called WorldCat, there are now 1156 books and thesis under the entry josé María Arguedas. About 15 years ago a group of academics and writers, mostly with Peruvian roots, founded Ciberayllu – loosely an Internet community in the field of Andean literature.

JMA (interrupting again) – I have just discovered Internet and feel that it would be the most wonderful tool for linking Quechua-speakers and of course the other regional languages too. Ciber-ayllu is an excellent name.

FS – On the subject of books about you and your life and so on, have you had a chance to read Vargas Llosa . . .

JMA – When he writes about indigenismo he criticizes the arguments used by the indigenista authors as barely substantiated: casi como ficciones. But they were mainly Euro-Peruvians and often they did not speak indigenous languages. Vargas Llosa might have asked why they had been limited to those arguments. Why could they not have “gone for the jugular” and simply condemn the treatment of campesinos as “an abuse of human rights.” In the 1920s the level of prejudice against the non Euro-Peruvian was so ingrained that the elite pretty much assumed that they were a race apart.

But either way I did not fit in too much with the indigenistas. Call me post-indigenista if you will. The difference is that I had grown up with indigenous people in their communities and spoke their language, sang their songs, recited their poetry. I knew their culture was completely undervalued and I felt . . . .

FS –That Peru could have had – and needed – a substantial bilingual literature, and not just in one variant of Quechua but in all Peruvian languages. But in the main that didn’t happen?

JMA –To be a writer of literature – one who is outstanding, even recognized internationally, say with a Nobel prize – one needs first of all, I would maintain, a high level of general literacy amongst the speakers of the language. The reason that a generation of Quechuista writers – of prose literature – has not evolved is simply that the Ministry of Education has impeded and in some cases forbidden that children should be educated in their parents’ language except where it is Spanish. In some ways all this activity by the Ministry of Culture – for which I am very grateful but also slightly bemused – serves as a smokescreen to cover up the fact that the Government still is teaching kids, in what to it are remote rural Quechua-speaking areas, in a second and initially almost- foreign language (Spanish). The Government still has no national training program for a corps of bilingual teachers in all Peruvian languages, it still has no history and cultural curriculum for our communities with multiple heritages, still no explicit policy for the rescue of threatened languages.

JMA –To be a writer of literature – one who is outstanding, even recognized internationally, say with a Nobel prize – one needs first of all, I would maintain, a high level of general literacy amongst the speakers of the language. The reason that a generation of Quechuista writers – of prose literature – has not evolved is simply that the Ministry of Education has impeded and in some cases forbidden that children should be educated in their parents’ language except where it is Spanish. In some ways all this activity by the Ministry of Culture – for which I am very grateful but also slightly bemused – serves as a smokescreen to cover up the fact that the Government still is teaching kids, in what to it are remote rural Quechua-speaking areas, in a second and initially almost- foreign language (Spanish). The Government still has no national training program for a corps of bilingual teachers in all Peruvian languages, it still has no history and cultural curriculum for our communities with multiple heritages, still no explicit policy for the rescue of threatened languages.

In short, nothing that could prepare a solid and massive base of competent writers and scholars from which would emerge reputed writers who also speak a regional language and can write equally well in either of their languages. One ray of hope is that I see that one presidential candidate supports the extension of the admirable Pukllasunchis program. . .

FS – The next question I find rather difficult to ask but many do want to know. Why did you commit suicide?

JMA – How did I get to the stage where I felt compelled to do it – that there was no other way out? All I can say is that there were things that used to depress me well before that critical stage. These I have set out in letters and diaries before the suicide. But what drove me on to do it I do not know – the timing rather than the decision. And in such a rational calculated manner: I find that hard to explain now other than to say “Look at the darkest point in your life and swear that you have not at least contemplated suicide.” Most at that stage draw back, but for me the pain of existence, the pain of consciousness as some would have it, was too much. People including Lola and Sybila (psychiatrist and wife, respectively) have guessed at explanations, and since then specialists have prognosticated even further. They say that I only provided proximate explanations and not ultimate ones – but it is the proximate that causes the pain.

JMA – How did I get to the stage where I felt compelled to do it – that there was no other way out? All I can say is that there were things that used to depress me well before that critical stage. These I have set out in letters and diaries before the suicide. But what drove me on to do it I do not know – the timing rather than the decision. And in such a rational calculated manner: I find that hard to explain now other than to say “Look at the darkest point in your life and swear that you have not at least contemplated suicide.” Most at that stage draw back, but for me the pain of existence, the pain of consciousness as some would have it, was too much. People including Lola and Sybila (psychiatrist and wife, respectively) have guessed at explanations, and since then specialists have prognosticated even further. They say that I only provided proximate explanations and not ultimate ones – but it is the proximate that causes the pain.

FS – To understand and feel what?

JMA – To understand the deep psychosis that develops when people are ripped, en masse, from their surroundings, their ayllus, their earth, their culture, the spiritual roots. Sociologists have come up with the word deracinated. In the Agonía de Rasu Ñiti I pointed to the importance of the continuity of cultural traditions: the danzante is reborn. The scissor-dance has now become a national dance – even spectacle – alongside the Marinera, but there are still many costeños who do not feel anything for Andean culture.

FS – Your critics would ask “Why should they?”

JMA – In a healthy society there needs to be mutual respect built on  understanding, on knowledge. Ironically the market economy, which should know a bargain when it sees it, has snapped up Andeans – in their urban transfiguration as the Cholo – and produced the boom economy of the last decade: no, it’s not all down to China, Peru plays its part as well. A hit musical, if it fused the grace of the Marinera with the athletics and symbolism of the Scissor Dance would be right for the times, even as huaynos and cumbias fused into chicha. You cannot compel a Euro-Peruvian to feel attracted to learning Quechua or to feel deeply moved by a yaraví let alone a huayno but you can provide the education, the knowledge and the sympathetic ambience by which these “magical” attributes of the national culture are valued. I have just heard something called, I think, chicha-techno-rock for the first time and that many of the musicians of the sierra are now to be found in the barriadas. Not all is bad – but what about the fate of Quechua. It seems to be the first casualty of the city.

understanding, on knowledge. Ironically the market economy, which should know a bargain when it sees it, has snapped up Andeans – in their urban transfiguration as the Cholo – and produced the boom economy of the last decade: no, it’s not all down to China, Peru plays its part as well. A hit musical, if it fused the grace of the Marinera with the athletics and symbolism of the Scissor Dance would be right for the times, even as huaynos and cumbias fused into chicha. You cannot compel a Euro-Peruvian to feel attracted to learning Quechua or to feel deeply moved by a yaraví let alone a huayno but you can provide the education, the knowledge and the sympathetic ambience by which these “magical” attributes of the national culture are valued. I have just heard something called, I think, chicha-techno-rock for the first time and that many of the musicians of the sierra are now to be found in the barriadas. Not all is bad – but what about the fate of Quechua. It seems to be the first casualty of the city.

FS – Before your death, a new government in favor of a “todas las sangres” approach came in, albeit a military dictatorship, and initially offered hope for the Andean: agrarian reform, Quechua language programs and so on. You were the leading expert on the Andean in Lima, you worked at the Agrarian University – surely you were the first person that General Velasco would have called on to lead, to advise and detail the agrarian, linguistic and cultural reforms. Almost as though you had been born for that moment after the coup d’etát? But you left for Chile and wrote a letter to Velasco . . .

FS – Before your death, a new government in favor of a “todas las sangres” approach came in, albeit a military dictatorship, and initially offered hope for the Andean: agrarian reform, Quechua language programs and so on. You were the leading expert on the Andean in Lima, you worked at the Agrarian University – surely you were the first person that General Velasco would have called on to lead, to advise and detail the agrarian, linguistic and cultural reforms. Almost as though you had been born for that moment after the coup d’etát? But you left for Chile and wrote a letter to Velasco . . .

JMA – It wasn’t that simple. The Belaunde government was not an evil repressive one. I supported some of its measures – they in a way were responding to Hugo Blanco. The Velasco government of 1969 initially offered (a misplaced) hope that finally the coast down below would understand the Andean from up above. But the lack of knowledge on their part . . . they came to destroy the social base of the few liberal voices – those who were fighting for Quechua and so on.

Does anyone know in the immediate period prior to their suicide why they are doing it? Maybe I asked for too great a concession from Velasco. Maybe there had not been enough time. The fact is my depression increased at this time – I’m not sure if I know whether this was related to the new government.

FS – You – we – now distinguish between the proximate and ultimate explanations for suicide. Readers in English know little about the events in the years leading up to December 2, 1969. Perhaps we should detail . .

JMA – I have read better explanations[iii] than I can provide but this is how my psychiatrist saw it. I began suffering from severe depression from the age of 32. Depression is such a general term but it meant decaimiento (feeling really down), tiredness, lack of concentration, insomnia, anxiety and a recurrent suicidal “ideation” (suicide kept filling my mind). But ultimately this stemmed from many factors such as: my mother dying when I was two, the cruelty of my stepmother and her son, the absence of my father who travelled a lot, the failure of my marriage, the fact I could not have children, the discrimination between the Andeans and the mestizos – did I belong to either? And my theories seemed to be of no use even when the Agrarian Reform arrived. They said I had a “biological predisposition to depression.”

FS / PT – Perhaps as we are running out of time, we could ask JMA for any final thoughts?

JMA – As a comment on the commemorations in general, they have on the whole been too nostalgic and backward looking. We do need to move forward and there is much that is better now for the Andean than 40 years and certainly 100 years ago. The rigid colonial attitude of the Euro-Peruvian towards the Andean-Peruvian, which was still prevalent in 1969, can now perhaps be found only in pockets (though some admittedly are rather substantial) of the Peruvian population. The danger now is that the zorro de arriba, the fox from up above – in the process of deracination which is called migration and out of sheer economic necessity – is forced to reject and forget a rich cultural heritage and particularly a rich and versatile language, be it one of the over twenty variants of Quechua, or Aymara, or the regional languages of the eastern lowlands and the cloud forest. A final request would be for the new government of Toledo (we suppose) to honor his promise to transform education. Not just by spending money but by introducing genuine bilingual (trilingual, if you include English) education and I like this idea of an Open University for all the language communities of Peru. That should be pursued.

JMA – As a comment on the commemorations in general, they have on the whole been too nostalgic and backward looking. We do need to move forward and there is much that is better now for the Andean than 40 years and certainly 100 years ago. The rigid colonial attitude of the Euro-Peruvian towards the Andean-Peruvian, which was still prevalent in 1969, can now perhaps be found only in pockets (though some admittedly are rather substantial) of the Peruvian population. The danger now is that the zorro de arriba, the fox from up above – in the process of deracination which is called migration and out of sheer economic necessity – is forced to reject and forget a rich cultural heritage and particularly a rich and versatile language, be it one of the over twenty variants of Quechua, or Aymara, or the regional languages of the eastern lowlands and the cloud forest. A final request would be for the new government of Toledo (we suppose) to honor his promise to transform education. Not just by spending money but by introducing genuine bilingual (trilingual, if you include English) education and I like this idea of an Open University for all the language communities of Peru. That should be pursued.

________________________________

[i] This article – really a short story – is faction (fact and fiction combined), therefore not history. However there are some who have learned much of their history from historical novels, including this writer. So on the rather dubious grounds that the end justifies the means (not an unknown topic of discussion in history) this brief look at Arguedas’ influence outside Peru is included in the history series – un-numbered but perhaps not unloved!

[ii] A composite of four women who knew Arguedas or worked in the field of what could be loosely termed Arguediana. The idea for a conversatorio or interview could be attributed to watching the rather zany but interesting verbal sparring spectacle between Aurelio Denegri and Carmen María Pinella on Channel 7 . . .

[iii] For example, there is a professional website called History of Psychiatry that looks at my own case! Shall we quote from that for the benefit of your readers. The original was, I think, in Spanish.

“In 1969, the writer, anthropologist and ethnologist José María Arguedas committed suicide after many years of depression that started in his youth, probably when he was 32 years old. According to the notes in the diaries of his book El Zorro de Arriba y el Zorro de Abajo and to the letters published afterwards, Arguedas showed multiple depressive episodes mainly characterized by decaimiento, tiredness, lack of concentration, insomnia, anxiety and a recurrent suicidal “ideation” that lead him to a first attempt in 1966 and to a second one which finished with his life despite the multiple treatments –pharmacological and psychotherapeutic- he received. Many theories have been suggested to understand the depression and suicide of the author of Yawar Fiesta, Los ríos profundos, El Sexto, Todas las sangres, and Amor mundo: the early loss of his mother, the step mother and brother’s cruelty, the absence of the traveling father, the failure of his marriage, the incapacity to have children, the feeling of being discriminated by both the native and the mistis worlds –without belonging to any- the failure of his integrative theories; maybe influenced by a biological predisposition to depression. We have to question if the depressive symptoms contributed to his work highlighted by nostalgia, marginality and ambivalence, and ask ourselves if Arguedas could have been part of literature history if he hasn’t had depression.”

___________________________________________

Paul Goulder: Academic and specialist on Latin America and Peru. Last academic posts: ENSCP-Paris; King’s College, University of London; UNSA, Arequipa, Peru. Also not-for-profit work in ecology, development and education in UK and Peru.

Paul Goulder: Academic and specialist on Latin America and Peru. Last academic posts: ENSCP-Paris; King’s College, University of London; UNSA, Arequipa, Peru. Also not-for-profit work in ecology, development and education in UK and Peru.

A true pedagogue! The deracination you mention seems particularly apparent among the Chagos islanders.