Paul Goulder returns with the second section of his History of Peru series special to the Peruvian Times. The first section, Parts 1 to 10, can be found listed at the end of this article.

The earthquake of August 15, 2007 centered on the Chincha – Pisco region had tragic but sometimes surprising consequences. It flattened the museum building in the Paracas National Reserve. Surviving exhibits were carted off to Ica. A new archaeology museum is being built on the same exposed site and an ecology museum is already up and running.

In the meantime, a new archaeology museum with a new, previously unknown collection has sprung up in the town center of Paracas. It is the inspiration and hard grind of essentially one man, Juan Navarro Hierro, who inherited the collection from his grandfather.

His house and collection was also severely damaged in the earthquake. It seems that the site was bulldozed without any rescue operation for the collection. However, astonishingly, almost one half of it survived.

His house and collection was also severely damaged in the earthquake. It seems that the site was bulldozed without any rescue operation for the collection. However, astonishingly, almost one half of it survived.

Following the earthquake, several well-known architects came forward with visionary plans for the reconstruction of the whole area to a ‘world-class’ standard. Pisco arising phoenix-like from the ashes, earthquake-proof churches and iconic museums were all part of the picture. However, the structure of property ownership and the “diversion” of government reconstruction bonds, among other factors, have left the visionary architects sitting on their hands. The long wait by Afro-Peruvians in the badly hit Chincha area for appropriate restitution (i.e. decent homes and an improved environment) is unresolved while the swanky consumerism of another Peru is provocatively displayed on the ‘billionaires’ mile’ which the stretch of beach south of the Paracas Hotel has become.

Above, an aerial view of the Paracas area: (1) the Museum, (2) Earthquake-hit properties, (3) Muelle El Chaco from where high-speed launches for the Ballestas run,(4) fishing fleets, and (5) the town plaza. Mixed in with the luxury beach villas of the nouveau and ancient riche of Peru’s economic booms are the ‘collection and selection’ hotels catering to the upper end of the tourist trade, including (6) the five-star-plus Libertador Paracas Hotel. At the other end of the billionaires mile, which starts to the south of the Paracas Hotel (7) are other deluxe hotels. Venture in the direction of (8) but much further out to sea and that would bring you to the artificial island from which giant LPG tankers can moor and take on quantities of Peruvian Camisea Natural Gas. The Ballestas Islands are in the direction of (9) but again a further 30 minutes out to sea. The islands, surrounded as they are by bountiful fish stocks (but dwindling through over-fishing), attract wildlife (seals, penguins, seabirds) and their “lovers” from around the world, plus a (very) few who are interested in the history of guano bird-dung and its bedfellow salitre/saltpeter/nitrate on the mainland or of the ill-fated Spanish occupation of the islands in 1863.

However, elite collections are nothing new in Paracas. When around 500 BC the Paracas people started entombing their upper class shrouded in the most fabulous fabrics, they little knew that these would be among some of the most ancient textiles surviving and of a quality that is hard to beat even or especially in the contemporary era.

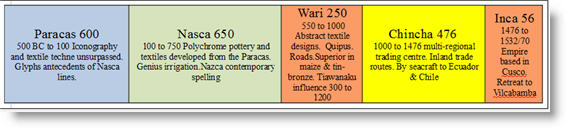

The museum presents a simple sequence of cultures in which to locate the textiles, ceramics, metals and other artifacts. Say “Penguins in Norway win classic internationals” – PNWCI. You are now half way to remembering the sequence (see below) of the archaeological periods Paracas Nasca area 500BC to Inca – indicating the approximate number of years for each cultural period. Width has been adjusted to show, but not to scale, that for example the Incas were present in the area for only 56 years whereas the Nasca culture lasted 650:

There is an intimate feel to the museum: you come within inches of the exhibits, you can talk to the curator, and the layout is traditional using glass showcases and labels – sometimes in English as well as Spanish or Quechua as appropriate. The museum, focusing on the early history of its area, uses a clear, simple model for classifying its pieces. It thus avoids the confusion of the National Museums which attempt to predicate a unifying theme for Peruvian pre-hispanic development and in which we so easily get Chimus, Chinchas, Chilcas, Chavins, Chimors confused with our Chichas, Chicas and Cholos.

There is an intimate feel to the museum: you come within inches of the exhibits, you can talk to the curator, and the layout is traditional using glass showcases and labels – sometimes in English as well as Spanish or Quechua as appropriate. The museum, focusing on the early history of its area, uses a clear, simple model for classifying its pieces. It thus avoids the confusion of the National Museums which attempt to predicate a unifying theme for Peruvian pre-hispanic development and in which we so easily get Chimus, Chinchas, Chilcas, Chavins, Chimors confused with our Chichas, Chicas and Cholos.

The sequence Paracas-Nasca-Wari

If someone bemoans the fact that “things don’t always get better” they may be referring to textiles! Here, on the right, is an example of a (circa 500 BC) Paracas textile now in the Pueblo Libre Museum, Lima (the Museum of Archaeology, Anthroplogy and History). For color and fine stitch-work these textiles have seldom been surpassed.

If someone bemoans the fact that “things don’t always get better” they may be referring to textiles! Here, on the right, is an example of a (circa 500 BC) Paracas textile now in the Pueblo Libre Museum, Lima (the Museum of Archaeology, Anthroplogy and History). For color and fine stitch-work these textiles have seldom been surpassed.

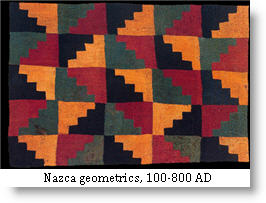

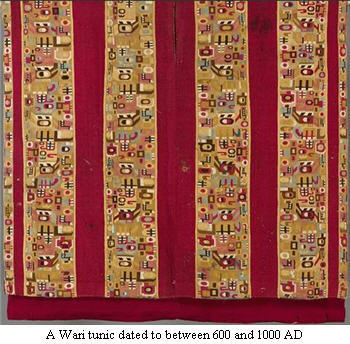

The tendency to a more geometric design is seen in the Nasca period (100 to 800 AD outside dates), while the later Middle Horizon, Wari style textile illustrated here is a tunic, dated to between 600 and 1000 AD. This mixed-fiber textile (camelid-fiber, probably alpaca weft, cotton warp, single-interlock tapestry) is in the Cleveland Museum collection.

The general theory that there was a cultural movement from the Nasca coastal pampa up towards the Ayacucho highlands is referred to as the Nazca-ization of the Sierra or highlands. So far the History of Peru Series has traced the development of Peruvian ‘civilisation’ from its early beginnings in the central coastal area north of Lima through approximately 3000 years. Subsequent articles will show how the Wari were able to fuse influences from the coast, from the selva (tropical eastern lowlands) and from the highlands in order to build – arguably – the first of Peru’s empires.

The general theory that there was a cultural movement from the Nasca coastal pampa up towards the Ayacucho highlands is referred to as the Nazca-ization of the Sierra or highlands. So far the History of Peru Series has traced the development of Peruvian ‘civilisation’ from its early beginnings in the central coastal area north of Lima through approximately 3000 years. Subsequent articles will show how the Wari were able to fuse influences from the coast, from the selva (tropical eastern lowlands) and from the highlands in order to build – arguably – the first of Peru’s empires.

The proprietor-curator of the Paracas Museum, Juan Navarro Hierro, having battled with the earthquake and its aftermath, is now fighting to persuade the tourism establishment in Paracas and tourists in general that a visit to the museum is worthwhile. The museum is competing with the Ballestas islands, the Paracas National Reserve and the billionaires’ playground which stretches between the Libertador Paracas “Selection” Hotel only a few hundred yards from the museum and the new upmarket Hilton. There is money in Paracas, at least for a few weeks – even months – a year. How can it be persuaded to take an interest in archaeology?

The proprietor-curator of the Paracas Museum, Juan Navarro Hierro, having battled with the earthquake and its aftermath, is now fighting to persuade the tourism establishment in Paracas and tourists in general that a visit to the museum is worthwhile. The museum is competing with the Ballestas islands, the Paracas National Reserve and the billionaires’ playground which stretches between the Libertador Paracas “Selection” Hotel only a few hundred yards from the museum and the new upmarket Hilton. There is money in Paracas, at least for a few weeks – even months – a year. How can it be persuaded to take an interest in archaeology?

Zotero bibliography | History of Peru Series: 1 Dawn Of Urbanization | 2 Tour 3000 BC To 500 AD | 3 Monumental Architecture | 4 Transition to Lima Culture | 5 Pucllana / Moche / Nazca | 6 Reading The Past (W)Righting | 7 Lima Culture and Water | 8 Ancient Textiles | 9 Metallurgy, Jewelry and Gold | 10 Big Picture & Index | Hidden Jewels | Looking Back | Backwardness | Country Notes | lanic-peru | bbc history of the world podcasts | evolving articles | study/research peru sas-isa | wikipedia articles on peru | other (oa) open access | oa archaeology | Guide to End Menu______________

Paul Goulder: Academic and specialist on Latin America and Peru. Last academic posts: ENSCP-Paris; King’s College, University of London; UNSA, Arequipa, Peru. Also not-for-profit work in ecology, development and education in UK and Peru.______________________________

Paul Goulder: Academic and specialist on Latin America and Peru. Last academic posts: ENSCP-Paris; King’s College, University of London; UNSA, Arequipa, Peru. Also not-for-profit work in ecology, development and education in UK and Peru.______________________________

PREVIOUS HISTORY OF PERU SERIES :

HISTORY OF PERU SERIES – Part 1: The Dawn Of Urbanization June 23, 2010 This was the first in a series of articles on Peru’s history, incorporating stories from the Peruvian Times archives, as well as links to videos, audio and other external sources to provide a rich background of information. This first part deals with the formation of the first towns and ceremonial sites in the Americas. […]

HISTORY OF PERU SERIES – Part 2: Tour 3000 BC To 500 AD July 3, 2010 The second in a series on Peru’s history takes you on a tour through time, visiting four historic sites. Between them they span more than 3000 years of Peru’s development and cover (Part 1) the first towns, (Part 3) the age of U-shaped monuments, Chavin and Garagay, (Part 4) the decline of the Chavin unifying culture or cult and the transition period typified by the Huallamarka truncated pyramid in San Isidro, Lima and (Part 5) Peru´s first golden age which saw the emergence of the Moche, the Lima (Pucllana) and the Paracas-Nasca cultures. […]

HISTORY OF PERU SERIES – Part 3: Monumental Architecture July 18, 2010 Across the world, the period 3000 BC to 500 BC (approx.) was an era of monumental architecture. Think Stonehenge (UK), Carnac (France). And then think of the pyramids of Egypt. In the case of Peru the giant structures took on the form of truncated, flat-topped pyramid platforms – sometimes arranged in the form of a U. […]

HISTORY OF PERU SERIES – Part 4: Transition – The decline of Chavín and the rise of the Lima Culture: Huallamarca August 4, 2010 Following Part 3 we have now arrived at approximately 200 BC in our time tour. We have traveled in the series from the beginnings of towns through a long stretch of Peruvian history in which the development of monumental architecture, irrigation systems, ceramics and textiles are underpinning more complex social, political and economic structures. Chavin had given its name to an iconographic style. This unifying “early horizon” may have had roots in other areas. For example the Garagay site in San Martin de Porres predates that of Chavin.[…]

HISTORY OF PERU SERIES – Part 5: The Pucllana / Moche / Nazca Period September 3, 2010 A.D. 200 – 650/800. The Lima Culture: Betwixt or Amidst the Moche and the Nasca. The fifth in the series looks on as the Lima (Lurin, Rimac and Chillon valleys) culture spreads its wings yet coexists with the more exuberant Moche to the north and Nazca to the south. Peru was not just all-Inca. […]

HISTORY OF PERU SERIES – Part 6: Reading The Past, Righting The Record November 13, 2010 A simple visit to the Pucllana huaca has provoked some simple questions: Where´s the water supply? What language did they speak? What did their clothes look like? Did they write? We are at 200/500 AD and there are no wheels on our wagons – in fact no wagons yet. Before we start our next “time-tour” let’s try to answer three key questions. What system for record-taking did the ancient Peruvians have – could it be called writing? (Part 7) How did the pre-Wari cultures tame the desert with only elementary technology? […]

HISTORY OF PERU SERIES – Part 7: The Lima Culture and WaterJanuary 21, 2011 If writing had been a “scarce commodity” in the Pucllana period, water was another: water has always been western Peru’s number-one scarce – but perversely sometimes too abundant – resource. There had been varying years of a desert climate interspersed with rare mud slides and flash floods […]

HISTORY OF PERU SERIES – Part 8: Ancient Textiles March 31, 2011. Part eight has an overall look at Peruvian Textiles. Anyone who touches this subject realizes their beauty and their complexity. Some of the oldest and most amazing textiles in the world were preserved in desert graves for posterity. Somewhat pre-Picasso, the Wari people and empire (Peru AD 600 to 900) were “abstract artists” abstracting barely recognizable yet iconic […]

HISTORY OF PERU SERIES – PART 9: Metallurgy, Jewelry and Gold May 4, 2011 This week we examined the tools historians possess for analyzing the impact of new technologies, particularly in metallurgy. In terms of a time-line, this part starts in an age of copper and ends as bronze makes an appearance. But all the time it is gold that steals the show. […]

HISTORY OF PERU SERIES: The Peruvian Times Guide to the “End Menu” May 4, 2011 The End Menu contains all the links necessary to turn you into the leading professor of Peruvian studies. Unfortunately the Peruvian authorities or the gods don’t want you to be and tolerate all sorts of non-neoliberal obstacles to your right to Access Critical Knowledge. The end menu looks like […]