By Daniel Buck

~ Special to Peruvian Times ~

How many argonauts have barreled headlong into the Andes and the Amazon, lusting for riches? No one can say for sure.

Alluring tales of wondrous lost civilizations built by gold and gem bedizened Indians have sparked the imaginations of European and North American treasure hunters ever since Atahualpa filled a 15-by-25 foot room with ransom gold for Pizarro.

Atahualpa’s ransom didn’t do the emperor much good — his conquistador captors executed him anyway — but dreams of similar riches in the lands of the former Inca empire have inspired countless gullible explorers and investors, often manipulated by swindlers. Here are some of their stories.

Entrepreneur Augusto R. Berns was not the first man to promise treasure in the Andes, but he might have been the most fanciful. His 1881 prospectus – written while he was living in Detroit, Michigan – for the development of an alleged gold property in Peru’s Urubamba Valley, informed potential investors that the region was more like “the south of France more than any other” place on earth.

The property, “Torontoy or Cercada-de-San Antonio Estate in Southern Peru,” an 8-by-18 square-mile section of the valley, not only rivaled Provence, but also contained a stairway and paved road that ascended to certain ruins, which Berns extravagantly called “The Towns of the Gold and Silver Smiths of the Andes.”

The property, “Torontoy or Cercada-de-San Antonio Estate in Southern Peru,” an 8-by-18 square-mile section of the valley, not only rivaled Provence, but also contained a stairway and paved road that ascended to certain ruins, which Berns extravagantly called “The Towns of the Gold and Silver Smiths of the Andes.”

Another auriferous trove on his land, “Llamajcansha,” Berns helpfully translated as “Gold Yard.” In reality, it means “Llama Yard.” Berns was selling his investors a load of llama dung.

All in all, Berns emphasized, “the WHOLE DISTRICT, generally, only requires to be known and opened up to be universally recognized as the greatest gold and silver producing centre in the world, and thus of immense value to any body of capitalists possessing really adequate means to profit by it in a MERCANTILE as well as mineral point of view.”

The enterprise would require the payment of a semi-annual $16 “mining License,” which would “entitle any proprietor to search for the precious metals or for hidden treasure (the last a common and sometimes lucrative occupation in Peru.)”

Berns was willing to sell the entire estate for $55,000 – more than a million dollars in today’s money – of which $30,000 was to pay off the mortgage, $15,000 to pay the claims of his former partners, and $10,000 to pay the expenses he had accrued. In other words, he was offering to sell what he had described as the “greatest gold and silver producing centre in the world” for nothing more than the amount of his outstanding debts.

But he set a high bar. His prospectus indicated that any buyer must be “a syndicate or company of bona fide capitalists,” willing to commit no less than $10 million – more than $200 million today – to the development of the property. The buyer must be agreeable to paying Berns $5,000 a year and, “as traveling is extremely expensive in Peru,” an additional $5,000 or more in annual travel expenses. In today’s money, that would be about $100,000 a year.

What became of the Torontoy scheme is not known. Today, some argue that Berns was referring to Machu Picchu, but the Torontoy property – assuming he even owned it – illustrated on his map was on the opposite side of the Urubamba River from Machu Picchu. In any event, there is no indication that any “bona fide capitalists” ever appeared at Berns’s door or that a single gold nugget was ever found.

Several years later, now back in Peru, Berns launched another scheme, the “Compañía Anónima Exploradora de las ‘Huacas del Inca’ Limitada,” and recruited eminent Peruvians and foreign residents, including the British vice consul in Mollendo, as board members or agents. The company’s prospectus said that the government of Peru “has guaranteed the success of our enterprise.” Hardly. In 1888, one year after “Huacas del Inca” was organized, its vice-president resigned, charging that Berns had been using company funds for personal use and had failed to launch a single treasure-hunting expedition.

If there was ever a man who lived up to Mark Twain’s adage that “a gold mine is a hole in the ground alongside of which stands a liar,” it was Raymond McCune. In 1912, he “floated a large corporation,” the Washington Post reported, “on the strength of having discovered the source of the gold of the ancient Incas.” Specifically, he organized two corporations, the Peruvian Exploration Company and Marañon River Placers, Inc., and fleeced investors to the tune of several hundred thousand dollars. Among the fleeced were prominent Delawareans, including members of the DuPont family.

McCune was an unlikely figure to get mixed up in such a fraud. His father, multi-millionaire Utah industrialist A.W. McCune, was a partner in the Cerro de Pasco copper mine in Peru and had extensive mineral holdings in the American West.

Raymond McCune claimed that his gold deposits, somewhere near the headwaters of the Marañon, were worth half a billion dollars, about $10 billion today. A prospectus went even further, saying that the enterprise’s directors “are of the opinion theirs are the most valuable gold-bearing placers yet discovered in the world’s history.” McCune predicted that earnings from the endeavor “ought to amount to $600,000 a year.”

One news account provided the back story: “The prospectus rehearsed some of the history of Pizarro and the Incas, and asserted the belief that the Incas’ ransom came from the Marañon River, for it explained: ‘The purpose of the numerous guard towers, the ruins of which are located on precipitous and well-nigh impregnable cliffs overhanging the Marañon River, was that the defenders of the gold washings standing on the tops of the cliffs might shower rocks on an attacking force without danger of their enemies being able to scale the cliffs.’”

McCune had reportedly “encountered an Indian of great age, who might be described as the last of the Incas, and who had revealed where the really rich deposits lay.”

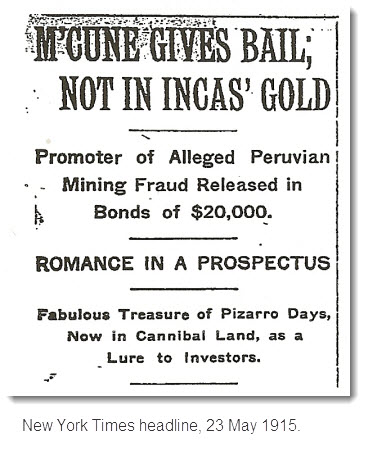

Who blew the whistle is unclear – perhaps one of the wealthy Delawareans – but in May 1915, McCune was arrested in New York City on charges of mail fraud. “McCUNE GIVES BAIL; NOT IN INCAS’ GOLD,” the New York Times headline quipped. A U.S. Postal Inspector spent six weeks in Peru “trying to locate the buried treasure of the Incas,” but “failed in his quest,” the Washington Post reported. “The natives told him they had never known of any gold in the vicinity.”

Who blew the whistle is unclear – perhaps one of the wealthy Delawareans – but in May 1915, McCune was arrested in New York City on charges of mail fraud. “McCUNE GIVES BAIL; NOT IN INCAS’ GOLD,” the New York Times headline quipped. A U.S. Postal Inspector spent six weeks in Peru “trying to locate the buried treasure of the Incas,” but “failed in his quest,” the Washington Post reported. “The natives told him they had never known of any gold in the vicinity.”

A year later, McCune was convicted of mail fraud and sentenced to four years in a federal penitentiary; a convicted co-defendant dropped dead of a heart attack at his sentencing.

A similar but more plebeian hoax lured a couple of hundred American prospectors to Bolivia in early 1912, when a man using the pen name “Ferguson” released a bogus letter to the press boasting of “enormously rich gold discoveries” along the Tipuani River. One news report said the letter writer was a German, but another said he was “an itinerant American miner, who previously had worked in Alaska.” Some 250 Americans answered fortune’s call according to the U.S. minister in La Paz. The German, a “fugitive from justice” known to local authorities, owned property on the Tipuani and he was eager to “boom the land.” Although there was gold in the Tipuani, the minister said that the “difficulties are such that only large enterprises and capital can handle the propositions successfully.” By July 1912, fewer than 25 American prospectors were still panning in Bolivia.

Macmillan’s, a popular magazine of the era, warned its readers that “South American treasures have, in fact, a thoroughly bad name, and investors should fight very shy indeed of shares in any of the numerous companies formed to empty sacred lakes or search the recesses of the Andes for Atahualpa’s hidden gold.”

Regardless, fortune hunters came and went, often with investors in tow. In July 1897, Captain A.G. Hatfield was outfitting his vessel Lancing in San Francisco, en route to Peru to hunt for “the treasure houses of the Incas,” per the Chicago Tribune.

“Captain Hatfield said that the expedition would probably consist of 500 men, but he refused to give the names of the leaders in the scheme, as negotiations had not yet been completed. He said: ‘All that I am at liberty to say in regard to this matter is that the men who have been negotiating with me are well known capitalists of San Francisco, who are responsible in every way.’”

The plan was to anchor the Lancing off the Peruvian coast: “Using the vessel as headquarters and a supply depot, parties will be sent to mineral regions to locate good properties.” The fate of Hatfield’s expedition is unknown.

Not all was gold in the Andes. A “Greek tavern keeper named Kalafatovich” found a rich deposit of emeralds “of the highest quality,” according to the Los Angeles Times. The deposit, found near near Acomayo, Peru, in 1912, was described, in the superlatives obligatory to such stories, as “one of the most important ever made in the world.”

On the shores of Lake Titicaca near the “City of Chililaya, . . . not far west of La Paz, once a great city of the Incas,” a group of American and European engineers uncovered “a portion” of the lost treasure of the Incas, again per the Los Angeles Times. Uncovered in 1904, this vast trove, “gold, silver, and precious stones” worth $14 million had been buried in 1780 and hunted ever since by “adventurers from every civilized nation on the globe.”

The Times article detoured into a potted history of the Incas, quoting experts as suggesting that the rulers of the Andes were culturally linked to the “‘Egyptians and Syrians’”or to Homer’s Ilium, which is to say Troy, or that the “‘gigantic architecture of Peru points to the Cyclopian family, the founders of the Temple of Babel, and of the Egyptian Pyramids.’”

The 1780 burial date for the Inca treasure was explained as follows: “The [Spanish] conquerors ruled with a heavy hand, when an Indian uprising occurred, and numerous bands surrounded the City of La Paz. The revolution spread, and the Indians avenged the wrongs which had been done to them from the beginning of the Spanish invasion. They ransacked the City of La Paz, taking all the remaining splendor of the Incas as well as the treasure found in other parts of the country. All of this was taken to the camp of the revolutionists.”

While the rebels marched on Cuzco, the treasure was buried between La Paz and Lake Titicaca. After the rebels’ defeat, the exact location of the treasure was lost to memory.

Although La Paz was never an Inca city, great or otherwise – it wasn’t even founded until 1548, by the Spaniards – there was an uprising of Indians and mestizos in 1780, the Túpac Amaru rebellion, which convulsed the Bolivian and southern Peruvian highlands for more than a year. The Chililaya treasure tale, however, has the chronology backwards. Cuzco was put to siege during the initial phase, but the Spaniards rallied and Túpac Amaru was captured. Though never ransacked, La Paz was under siege for several months in late 1781 before colonial troops from Buenos Aires came to the city’s rescue.

According to the Times, a European syndicate had hired a group of prospectors who began the search in Puno and worked their way around Titicaca until, near Chililaya, they struck gold. There is no community named Chililaya in Bolivia, but west of La Paz, near the lake, are two Indian settlements, Chichilaya and Cachilaya either of which might be the site referred to. One of the prospectors’ Indian guides reported the find to the authorities in La Paz and the treasure quest had been shut down by the government. So ended this particular installment of the hunt for the lost treasure of the Incas, assuming it ever happened to begin with.

Incan troves were erupting in 1904. According to a wire service report, a team of British and American engineers stumbled upon a treasure “of the purest gold” worth $16 million at Chayaltaya, Bolivia, and expected that $30 million more was “awaiting a discover.” There is no place named Chayaltaya, but perhaps it was the mountain Chacaltaya, the site of Bolivia’s only ski run, the highest in the world.

The gold had been collected by the Indians, the story said, “to be paid over to the Spaniards as a ransom for the liberation of Emperor Atahualpa but the money was refused by the Spaniards, who killed the Peruvian emperor, and the treasure remained hidden.” The engineers found the gold by accident while driving survey stakes.

Two years later, in 1906, came “Buried Treasures of the Incas,” a story in the New York Times, indicating that maybe the Incan treasure was not on the shores of Lake Titicaca, but in the lake itself: “The lake, it is believed, would, if dredged, yield up thousands of [gold and silver images] and similar precious gold articles thrown in [the lake], it is alleged, both as a sacrifice and to prevent them from falling into the hands of Pizarro’s band.” The lake was not dredged.

Hiram Bingham, who came to Peru in the 1910s to hunt for lost cities, got snared by the treasure-of-the-Incas legend. In 1915, during Bingham’s third and final expedition to Machu Picchu and nearby ruins, local officials came to believe he was smuggling Inca gold from his excavations out of the country. “Bingham learned with amazement,” Alfred Bingham wrote in his biography of his father, Portrait of an Explorer, that a Cuzqueño newspaper editor had published an article “reporting rumors of the export of gold by way of Bolivia. Controlling his anger, [Bingham] denied that he had exported anything, much less gold, and offered to open any of the boxes” for inspection. A Peruvian delegation sent to La Paz to investigate the matter found nothing, and Bingham himself obtained an affidavit from the port authorities in Puno attesting that he had shipped nothing gilt.

The Jesuits stood in for the Incas in the Sacambaya legend, which has been attracting argonauts for more than a century. As the well-worn tale goes, when the Jesuits were expelled from South America in the 1760s, the contingent at the Sacambaya mission, at the junction Apopaya and Khatu rivers in Bolivia, near the border between the La Paz and Cochabamba departments, ordered local Indians to construct an elaborate multi-alcoved cave in which was hidden a vast treasure, worth a billion dollars today. The Indians, who numbered from half a dozen to several hundred in the various accounts, were then murdered by the Jesuits and buried in the cave, which was sealed. Upon the Jesuits’ return to Rome, they were imprisoned and all but one executed.

As luck would have it, the surviving Jesuit returned to Bolivia, and had a daughter by his mistress. The daughter later took up with an Englishman and spilled the Sacambaya secret to him. A woman is a constant in stories of how the secret was divulged.

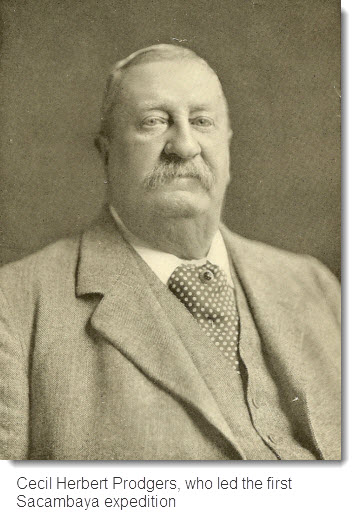

A succession of Europeans fell for the Sacambaya yarn. The first was Cecil Herbert Prodgers, a six-foot tall, 265-pound Englishman who had fought in the Boer War, raced horses in Peru, and tapped rubber in Bolivia. He claimed to have been given a document about the treasure by none other than the daughter of the president of Peru. The treasure, his document said, consisted of $90,000 in silver, 67 “heaps of gold,” and gold ornaments adorned with diamonds and other precious stones hidden in a maze of rooms, compartments, and hollows booby-trapped with “enough strong poison to kill a regiment.”

A succession of Europeans fell for the Sacambaya yarn. The first was Cecil Herbert Prodgers, a six-foot tall, 265-pound Englishman who had fought in the Boer War, raced horses in Peru, and tapped rubber in Bolivia. He claimed to have been given a document about the treasure by none other than the daughter of the president of Peru. The treasure, his document said, consisted of $90,000 in silver, 67 “heaps of gold,” and gold ornaments adorned with diamonds and other precious stones hidden in a maze of rooms, compartments, and hollows booby-trapped with “enough strong poison to kill a regiment.”

In 1905, Prodgers gathered a troupe of laborers and set off for Sacambaya. The rainy season halted work, but they returned the next year. His workers punctured the treasure cave’s roof but were overcome by “a very powerful smell.” A new crew came in and they were also struck down by toxic vapors, as was Prodgers, who said his fingernails turned blue. He called off the hunt. He tried to return in 1907, but neither could attract investors nor willing laborers.

English explorer Percy Harrison Fawcett heard about the treasure a few years later from William Tredinnick, a Cornishman who said that he had been in a partnership with descendants of the surviving Jesuit. (Some years earlier Tredinnick had been jailed in Bolivia for a robbery some attribute to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.) Fawcett went to Sacambaya for a look-see. “My opinion is,” Fawcett later wrote, “if a treasure really exists there, then attempts to find it have not been carried out very intelligently.” He thought that if the clues were followed, it would be a “simple matter” the settled the question once and for all. Simplicity notwithstanding, he didn’t bite. “It didn’t ‘feel’ as though the treasure were buried there,” he wrote, “and I am inclined to give some weight to my impressions.”

Fawcett’s instincts failed him a few years later when he disappeared in the Mato Grosso while searching for “Z,” a lost city of “clothed natives of European appearance.”

But the hunt for Sacambaya’s fabled fortune was not over. In the 1920s, Prodgers passed his documents to Edgar Sanders, a Russian-born Swiss citizen living in England. After a couple exploratory visits to Bolivia, Sanders returned to England, announcing that he had excavated a “man-made cave,” inside of which he had found a crucifix and a parchment. The ancient document, written in Spanish, warned: “You who reach this place withdraw! This spot is dedicated to God Almighty and one who dares enter, a dolorous death in this world and eternal condemnation in the world he goes to.”

Eternal damnation did not deter Sanders from offering $125,000 in stock in the Sacambaya Exploration Company, promising a heavenly 48,000 percent return to investors. The stock sold quickly, and in 1928 Sanders found himself back in Bolivia with a crew of 20 and a caravan of trucks loaded with tons of gear – mining equipment, suction pumps, compressors, gas masks (for the fabled toxic vapors), food, and an array of weaponry. After several months of fruitless digging, the rainy season shut down the project.

Sacambaya lay undisturbed until the 1960s, when two Englishmen, Mark Howell and Tony Morrison, came calling with “field distortion locating equipment,” essentially a metal detector capable of penetrating at least 20 feet of soil or rock. Howell and Morrison hauled their metal detector to a number of locations at the Sacambaya junction, but the only metal they found was a trapezoidal copper plate, possibly a relic of the Sanders expedition. The rains came, and Howell and Morrison went home.

Reached at his home in England several years ago, Morrison was still hopeful. He said by email that “there are excellent but still unproven reasons for the existence of a treasure,” though he surmised that it “could be in any one of thirty places.”

Howell and Morrison’s guide, Juan Oroya, came as close as anyone to deciphering the Sacambaya mystery. As Howell recounts it in Steps to Fortune, Morrison’s and his book about their adventures, he asked Oroya: “Juan . . . why has no one ever found the treasure? You live here. You must have heard stories, and have your own ideas.”

“It’s a gringo treasure,” Oroya said.

FURTHER READING:

Alfred Bingham, Portrait of an Explorer (1989); Daniel Buck, “Tales of Glitter or Dust,” Américas, May/June 2000; Col. P.H. Fawcett, Lost Trails, Lost Cities (1953); Mark Howell and Tony Morrison, Steps to a Fortune (1967); Stratford D. Jolly, The Treasure Tale (1934) and South American Adventures (n.d.); Alicia Overbeck, Living High (1935); C.H. Prodgers, Adventures in Bolivia (1922); and James Stead, Treasure Trek (1936).

Daniel Buck lives in Washington, DC. He was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Puno, 1965-1967

I have been researching Muskegon Michigan 1907the only two buried treasure stories I have been able to find are ole Larson pot of gold in wood factory1902 Muskegon Michigan or Ludington Michigan and bidwell brothers mona lake Muskegon mi9chigan robbed bank of England and buried the loot looking for furher information on Muskegon Michigan alcapone 1930did he stay at mona lake is his treasure buried there