By Annie Thériault —-

Thirty-nine years ago this Sunday, on May 31, 1970, an undersea earthquake off the coast of Casma and Chimbote, north of Lima, triggered one of the most cataclysmic avalanches in recorded history – wiping out the entire highland town of Yungay and most of its 25,000 inhabitants.

Yungay 1970

Around 3:23 PM, local time, while most were tuned in to the Italy-Brazil FIFA World Cup Match, a magnitude 8.0 earthquake struck the Peruvian departments of Ancash and La Libertad. The quake’s epicenter was located in the Pacific Ocean, where the Nazca Plate is subducted by the South American Plate, and recorded a magnitude of 8.0 on the Richter scale, with an intensity of up to 8 on the Mercalli scale.

Lasting 45 seconds, the earthquake crumbled adobe homes, bridges, roads and schools across 83,000 square kilometers, an area larger than Belgium and the Netherlands combined. Registered as one of the worst earthquakes ever to be experienced in South America, damages and casualties were reported as far as Tumbes, Iquitos and Pisco, as well as in some parts of Ecuador and Brazil.

In Yungay, a small highland town in the picturesque Callejon de Huaylas, founded by Domingo Santo Tomás in 1540, the earthquake triggered an even greater calamity.

The quake destabilized the glacier on the north face of Mount Huascarán, causing 10 million cubic meters of rock, ice and snow to break away and tear down its slope at more than 193 kilometers, or 120 miles, per hour.

As it thundered down toward Yungay, and the town of Ranrahirca on the other side of the ridge, the wave of debris picked up more glacial deposits and began to spit out mud, dust, and boulders. By the time it reached the valley – barely three minutes later – the 914 meters-, or 3,000 feet-wide wave was estimated to have consisted of about 80 million cubic meters of ice, mud, and rocks.

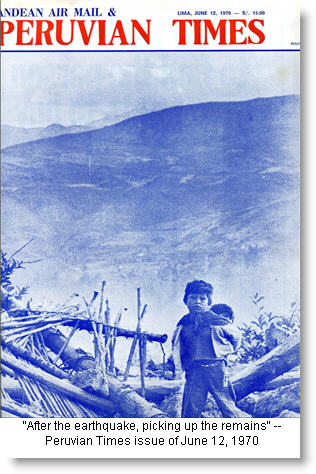

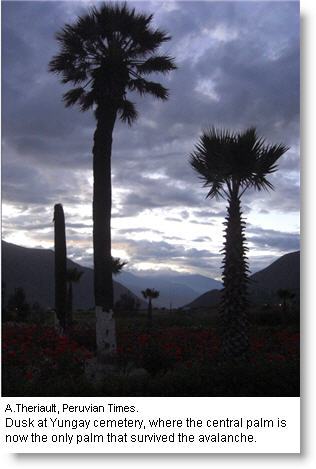

Within moments, what was Yungay and its 25,000 inhabitants – many of whom had rushed into the church to pray after the earthquake struck – were buried and crushed by the landslide. The smaller village of Ranrahirca was buried as well, the second time in a decade, but it is the image of lone surviving palm trees in the Yungay cemetery that is burned into Peru’s memory.

“We were on our way from Yungay to Caraz when the earthquake struck,” survivor Mateo Casaverde recalls.

“When we stepped out of the car, the earthquake was almost over. Then we heard a deep, low rumble, something distinct from the noise an earthquake makes, but not too different. It came from the Huascarán. Then we saw, half-way between Yungay and the mountain, a giant cloud of dust. Part of the Huascarán was coming toward us. It was approximately 3:24. Where we were, the only place that offered us relative security, was the cemetery, built upon an artificial hill, like a pre-Incan tomb. We ran approximately 100 meters before we got to the cemetery. Once I reached the top, I turned to see Yungay. I could clearly see a giant wave of gray mud, about 60 meters high. Moments later, the landslide hit the cemetery, about five meters below our feet. The sky went dark because of all the dust, mostly from all of the destroyed homes. We turned to look, and Yungay, as well as its thousands of inhabitants, had completely disappeared.”

The reported death toll from what came to be known as Peru’s Great Earthquake totaled more than 74,000 people. About 25,600 were declared missing, over 143,000 were injured and more than one million left homeless. The city of Huaraz was rubble, the valley buried in mud, and coastal towns such as Casma were also shaken to the ground.

In Yungay, only some 350 people survived, including the few who were able to climb to the town’s elevated step-like cemetery. Built between 1892 and 1903, the cemetery was designed by Swiss architect Arnoldo Ruska, who also died as a result of the landslide.

Among the survivors were 300 children, who had been taken to the circus at the local stadium, set on higher ground and on the outskirts of the town.

“The clown led the children to safety like the Pied Piper,” Henri Gómez, a local tourist guide told the Peruvian Times. “As soon as the earthquake struck, he led them from his tent to higher ground.”

Today, Yungay is a national cemetery, and the Huascarán’s victims are still vividly remembered.

Because the Peruvian government has forbidden excavation in the area, crosses and tombs mark the spots where homes once stood, engraved with the names of those never found.

To this day, a crushed intercity bus, four of the original palm trees that once crowned the city’s main plaza and remnants of the cathedral still stand.

And, though life goes on and a new Yungay has since been rebuilt – a few kilometers away from the original city – Peru does not want to forget. In 2000, in memory of the victims of the deadliest seismic disaster in the history of Latin America, the government declared May 31 “Natural Disaster Education and Reflection Day.”

Pingback: My Journey Through South America Where I Took The Road Less Traveled: PART ONE • MMI Communication, LLC