By Paul Goulder — Special to Peruvian Times —

The idea of “living history tours” to touch the stones of our ancestors is not new for readers of the Peruvian Times. Dipping into the archives reveals articles written by Peggy Massey and several others over the years (the 1960s in this case) on key early history sites, and these will soon be available on line.

The idea of “living history tours” to touch the stones of our ancestors is not new for readers of the Peruvian Times. Dipping into the archives reveals articles written by Peggy Massey and several others over the years (the 1960s in this case) on key early history sites, and these will soon be available on line.

To these sites have been added the more recently investigated Caral and the neglected but monumental Garagay to make up a “first tour.” A detour to the oldest and largest of Lima’s archaeological sites from the age of “architectural monumentalism” (El Paraíso) is also shown on the map of the “time tour.”

If you are new to Lima and know little of the earlier history of the area, this is one tour you can do on your own that takes you to four (five, if you are super-energetic) important historical sites in two days. Together these sites summarize the “first 3700 years” or so of Peruvian history since cities began about 5000 years ago.

Moreover, these sites interlock with each other (but with some gaps) in the complex jigsaw puzzle that is Peruvian time and space (but as you’ll see, there are some missing pieces before 200 BC). This leaves a cool 1310 years to be “done” in further history-journeys covering the period since 700 AD or thereabouts, when the fourth site to be visited, Pucllana, is abandoned and converted into a cemetery for the Wari Empire.

How to get there (if you live far from the Lima area or find mobility difficult, future articles will provide a virtual tour.)

1. Caral 3000 BC (as a separate day trip). Up-to-date information on Caral is provided on the Caral-Supe website. An interprovincial bus towards Barranca stops at Supe Pueblo (at the Mercado de Supe) on the Panamericana Norte Km 187. From there a taxi-colectivo (3.50 soles) goes to Caral pueblo with a walk of 20 minutes to the site. All travel agencies offer tours, of course, but there are also organized bus-trips (see Caral Supe website) direct from the Museo de la Nación in San Borja, Lima, which are well-worth taking. You get an eloquent talk and a video to brief you before you arrive.

1. Caral 3000 BC (as a separate day trip). Up-to-date information on Caral is provided on the Caral-Supe website. An interprovincial bus towards Barranca stops at Supe Pueblo (at the Mercado de Supe) on the Panamericana Norte Km 187. From there a taxi-colectivo (3.50 soles) goes to Caral pueblo with a walk of 20 minutes to the site. All travel agencies offer tours, of course, but there are also organized bus-trips (see Caral Supe website) direct from the Museo de la Nación in San Borja, Lima, which are well-worth taking. You get an eloquent talk and a video to brief you before you arrive.

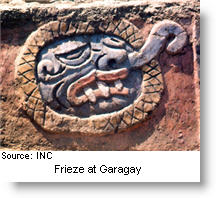

2. Garagay 1340 BC. Note that this site has no security and is in a relatively deprived part of town. Try to go on a visit organised by the Ministry of Culture or by the San Marcos or Católica universities, which are, after all, on the same road (one of the longest in Lima). We took a micro (smallish bus, sometimes called a Coaster pronounced Custer, not presumably because they are regularly reported as mowing down pedestrians or because of the wounded knees and other injuries inflicted when ascending the access steps), to the Universidad Católica on Avenida Universitaria not far from the San Miguel shopping center and Avenida de la Marina. From the taxi stand at the Católica take an official taxi (the yellow ones outside the main gate) to Garagay (block 28 of the same avenue, Avenida Universitaria, having crossed the Rio Rimac) near the intersection with Av. Gamarra, San Martín de Porres. It’s difficult to find because many locals think it’s just another hill or mound, although the site is vast. The huaca has an electricity pylon (torre de alta tensión) on top. Get the taxi to do the round trip. If you speak Spanish and know Lima you can do the whole excursion more cheaply.

2. Garagay 1340 BC. Note that this site has no security and is in a relatively deprived part of town. Try to go on a visit organised by the Ministry of Culture or by the San Marcos or Católica universities, which are, after all, on the same road (one of the longest in Lima). We took a micro (smallish bus, sometimes called a Coaster pronounced Custer, not presumably because they are regularly reported as mowing down pedestrians or because of the wounded knees and other injuries inflicted when ascending the access steps), to the Universidad Católica on Avenida Universitaria not far from the San Miguel shopping center and Avenida de la Marina. From the taxi stand at the Católica take an official taxi (the yellow ones outside the main gate) to Garagay (block 28 of the same avenue, Avenida Universitaria, having crossed the Rio Rimac) near the intersection with Av. Gamarra, San Martín de Porres. It’s difficult to find because many locals think it’s just another hill or mound, although the site is vast. The huaca has an electricity pylon (torre de alta tensión) on top. Get the taxi to do the round trip. If you speak Spanish and know Lima you can do the whole excursion more cheaply.

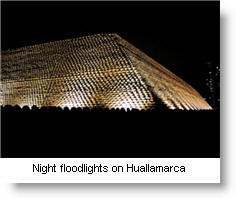

3. Huallamarca 200 BC in San Isidro is three blocks from the Virgen del Pilar church and óvalo (roundabout / traffic circle). If coming from Garagay, get the taxi on the return leg to take you right down past the Católica to the Avenida de la Marina. From there, if you would like to “save a few bob”, take a micro to the Camino Real intersection with Choquehuanca, San Isidro. Walk west down Choquehuanca three blocks. The huaca is also known as the “Sugarloaf” or Pan de Azucar – the name, I believe, of the hacienda or farm / country estate that had been here prior to being built over. Thousands have passed by Huallamarca without realizing its significance. Some believe it’s not genuine – it looks too pristine, precise: what you see is an outer covering of maize-shaped adobe blocks applied in the 1950-60’s but the compact (small but informative) on-site museum provides clues to its role in the remarkable transformation from the age of “monumentalism” to an established “Lima culture” around 200 BC. Huallamarca is a contemporary of the magnificent (stage II) Paracas culture. The Huallas were among the people (Limeños in all but name) on whose shoulders the Lima culture rested.

3. Huallamarca 200 BC in San Isidro is three blocks from the Virgen del Pilar church and óvalo (roundabout / traffic circle). If coming from Garagay, get the taxi on the return leg to take you right down past the Católica to the Avenida de la Marina. From there, if you would like to “save a few bob”, take a micro to the Camino Real intersection with Choquehuanca, San Isidro. Walk west down Choquehuanca three blocks. The huaca is also known as the “Sugarloaf” or Pan de Azucar – the name, I believe, of the hacienda or farm / country estate that had been here prior to being built over. Thousands have passed by Huallamarca without realizing its significance. Some believe it’s not genuine – it looks too pristine, precise: what you see is an outer covering of maize-shaped adobe blocks applied in the 1950-60’s but the compact (small but informative) on-site museum provides clues to its role in the remarkable transformation from the age of “monumentalism” to an established “Lima culture” around 200 BC. Huallamarca is a contemporary of the magnificent (stage II) Paracas culture. The Huallas were among the people (Limeños in all but name) on whose shoulders the Lima culture rested.

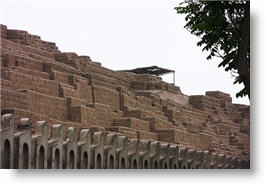

4. Pucllana 400 AD From Huallamarca walk back to Camino Real and take a micro south to one stop beyond the Ovalo Gutierrez. Alternatively, a taxi ride is comparatively short and here the drivers will know the huaca (probably!). Pucllana was previously known as the Huaca Juliana – old hands prefer this name, as apparently the name Pucllana was imposed by a military government. The 300 years following the building of Huaca Juliana were to prove a period of exceptional development contemporary with the brilliant Moche and Nazca cultures. One of the great “belles époques” of Lima.

4. Pucllana 400 AD From Huallamarca walk back to Camino Real and take a micro south to one stop beyond the Ovalo Gutierrez. Alternatively, a taxi ride is comparatively short and here the drivers will know the huaca (probably!). Pucllana was previously known as the Huaca Juliana – old hands prefer this name, as apparently the name Pucllana was imposed by a military government. The 300 years following the building of Huaca Juliana were to prove a period of exceptional development contemporary with the brilliant Moche and Nazca cultures. One of the great “belles époques” of Lima.

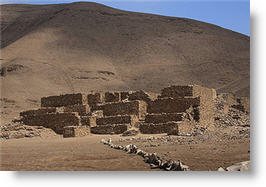

5. El Paraíso 2000 BC. If you have just that bit of extra energy you might consider adding El Paraíso (paradise) – the earliest and largest of the monumental sites overlooking the River Chillón – to this list. Or substitute it for Garagay. Micros: Ventanilla buses passing Jorge Chavez airport will take you to the access routes:

5. El Paraíso 2000 BC. If you have just that bit of extra energy you might consider adding El Paraíso (paradise) – the earliest and largest of the monumental sites overlooking the River Chillón – to this list. Or substitute it for Garagay. Micros: Ventanilla buses passing Jorge Chavez airport will take you to the access routes:

(1) get off at the Jardines de Oquendo, part of the old, wealthy Fundo de Oquendo, and walk up the hillside behind the “gardens”. Go at weekends and there may be other people around, particularly the mountain bikers that use the ruins as a practice circuit – ideal and suitably sacrilegious, but be quick to step out of their way! At solstice time modern-day indigenistas / neo-druids / lovers of Peruvian traditions will parade the grounds á la Stonehenge and Inti Raymi at Cusco. Why not join them? From time to time the more enthusiastic (reckless?) and heritage-minded of teachers will guide their school-kids up onto the sacred site where they will go bezerk hiding from each other and also presumably from the teacher.

(2) Stay on the bus until just before the river crossing. There you may be able to pick up a one-sol moto-taxi to take you part of the way up the incline. I have not done route 2 personally so cannot give it the all-clear. There is always this thing that certain zones are supposed to be death-traps for pitucas and gringos! In fact it is the local population that suffers the brunt of the crime. El Paraíso is a detour from the main route and our advice is go with a group or an organized tour. (You cannot see El Paraíso from the road as you can Garagay.)

In our time-tour El Paraíso provides a “longer missing link” (between 2000 BC and 200 BC). Garagay, on the other hand, appears to have been hit by flooding or a huaico (mud-slide) by about 1000 BC. However, understanding Garagay is fundamental to the development of a cohesive history of Lima and the neglect it has suffered since the excavations of the 1970s led by Roger Ravines and his team is a disaster for Peru. Garagay has iconographic and perhaps religious links with Chavin (video in Spanish) during what archaeologists call the early horizon period.

In our time-tour El Paraíso provides a “longer missing link” (between 2000 BC and 200 BC). Garagay, on the other hand, appears to have been hit by flooding or a huaico (mud-slide) by about 1000 BC. However, understanding Garagay is fundamental to the development of a cohesive history of Lima and the neglect it has suffered since the excavations of the 1970s led by Roger Ravines and his team is a disaster for Peru. Garagay has iconographic and perhaps religious links with Chavin (video in Spanish) during what archaeologists call the early horizon period.

Comment on this article | See a Zotero bibliography and “list of links with notes” on Peruvian studies| Help edit an extended “evolving” article on this topic | Find other articles in the “wiki” domains on internet about early Peruvian archaeological sites | Add your own article to the online collection – click on link and then on “Create new article” in left margin menu.

Incidentally: Sendero Luminoso blew up the Garagay pylon not once but twice in the 1980’s. Sadly the electricity company did not take the opportunity to relocate the pylons away from this important Lima heritage site, in spite of pressure from archaeologists and historians to do so.

NEXT PART: If 2500BC to 500BC (approx.) is the age of monumental architecture (truncated pyramid platforms arranged in a U shape) then surely the bigger they are, the better they are. We assemble the satellite images of the four sites in the Time-Tour to compare dimensions. Simple, basic “complexity” where size matters: birds-eye view of four key sites 3000 BC to 700 AD. Plus: see where the site is on the “Google-map” so you don’t get lost. Monumental masons: the architecture of enforced / corporate labor

_______________________

Paul Goulder: Academic and specialist on Latin America and Peru. Last academic posts: ENSCP-Paris; King’s College, University of London; UNSA, Arequipa, Peru. Also not-for-profit work in ecology, development and education in UK and Peru.

Paul Goulder: Academic and specialist on Latin America and Peru. Last academic posts: ENSCP-Paris; King’s College, University of London; UNSA, Arequipa, Peru. Also not-for-profit work in ecology, development and education in UK and Peru.