A.D. 200 – 650/800 – The Lima Culture: Betwixt or Amidst the Moche and the Nasca

By Paul Goulder —The fifth of a series of articles on Peru’s history, incorporating stories from the Peruvian Times archives, as well as links to videos, audio and other external sources to provide a rich background of information. —

Two seemingly archaic words, betwixt and amidst, summarize the history riddle for this part of the series. Peru had two world-renowned cultures in the Moche (on the north coast) and Paracas-Nazca (on the south coast). Should we write “Squeezed betwixt these giants, who were notoriously hungry for trophy heads and sacrificial victims of war, lies the ancient Lima Culture (central coast),” or “Flourishing amidst the rich and vibrant cultural influences from the north and the south we find a growing culture which we now call the Lima.” Which was it: amidst or betwixt? Switzerland or Afghanistan? A multi-lingual polity at peace with its neighbors or a failed, war-torn buffer zone?

Two seemingly archaic words, betwixt and amidst, summarize the history riddle for this part of the series. Peru had two world-renowned cultures in the Moche (on the north coast) and Paracas-Nazca (on the south coast). Should we write “Squeezed betwixt these giants, who were notoriously hungry for trophy heads and sacrificial victims of war, lies the ancient Lima Culture (central coast),” or “Flourishing amidst the rich and vibrant cultural influences from the north and the south we find a growing culture which we now call the Lima.” Which was it: amidst or betwixt? Switzerland or Afghanistan? A multi-lingual polity at peace with its neighbors or a failed, war-torn buffer zone?

Which should it be?

Pucllana and the Lima Culture from 200 AD

Pucllana and the Lima Culture from 200 AD

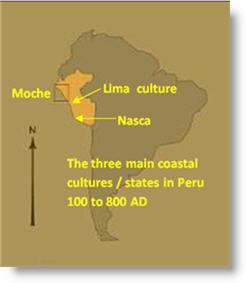

In this Peruvian Times tour of early Peru we are now visiting the fourth site, Pucllana or the Huaca Juliana, part of the “intermediate” Lima Culture. Please see Part 2 for map and Part 3 for aerial views and context. I hope that during the course of the next five parts of the series – which all have to do with the same time period as Pucllana, approximately 200-800 AD – a more intimate understanding of this remarkable era in Peru’s development will emerge. It is remarkable also because of the “flowering” of two neighboring cultures: those of the Moche and the Nasca. On the map, shown left, a median date of 400 is given. Archaeologists at Pucllana told us that the earliest dating for the site is 200, about the time that Huallamarca – see Part 4 – is being given up for use as a cemetery.

Taken together, the parallel growth of the Moche, Nasca and Lima cultures bear witness to a sea-change[1] in the overall development of the coastal areas of what is now called Peru.

Moche, Nasca and the Lima culture (Pucllana)

The Moche lived in the north-coastal valleys – from well to the south of Trujillo to north of Chiclayo – between 200 and 800 AD, whilst the Nasca occupied valleys of the southern coast at approximately the same time, and by 200 the Nasca were already flourishing, standing on the shoulders of the earlier Paracas culture. This appears to leave little space for an independent [2] Lima culture wedged[3] in-between. This part of the series takes the view that the Lima culture was more than a “wedge” or intermediary between two relative giants, culturally speaking — alongside the Moche and Nasca cultures although there is a problem: none of the exquisite Paracas-style embroidery can be attributable to the Lima area – or to the Moche for that matter. Neither Nasca nor Lima make significant use of the sculptural forms of Moche ceramics nor the improvements in the use of molding and other technical refinements.

The Moche lived in the north-coastal valleys – from well to the south of Trujillo to north of Chiclayo – between 200 and 800 AD, whilst the Nasca occupied valleys of the southern coast at approximately the same time, and by 200 the Nasca were already flourishing, standing on the shoulders of the earlier Paracas culture. This appears to leave little space for an independent [2] Lima culture wedged[3] in-between. This part of the series takes the view that the Lima culture was more than a “wedge” or intermediary between two relative giants, culturally speaking — alongside the Moche and Nasca cultures although there is a problem: none of the exquisite Paracas-style embroidery can be attributable to the Lima area – or to the Moche for that matter. Neither Nasca nor Lima make significant use of the sculptural forms of Moche ceramics nor the improvements in the use of molding and other technical refinements.

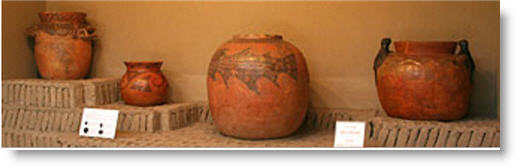

Pucllana Pottery

That does not mean that the Lima and central coastal area is devoid of good ceramics. The beautiful designs on ceramics produced in this period are represented here by a detail from a vessel contemporary to Pucllana. Approx 200-600. This and other tourism websites bear witness to the pulling power of the three H’s: history, heritage and historiography (in short: When, Wow and How). For historians and the Peruvian travel industry this is cheering news as other country-destinations fight over the promotion of the S’s: sun, sand, sea, surfing, sailing. At one time it was S’s in the north and H’s in the south of Peru. But no longer, now that the Moche circuit is on stream. Below, the larger vessel in the Pucllana site museum carries the characteristic killer whale or shark, confirming the importance of the maritime economy to the people of the Lima culture and of Pucllana itself, from which you can see the sea – just.

That does not mean that the Lima and central coastal area is devoid of good ceramics. The beautiful designs on ceramics produced in this period are represented here by a detail from a vessel contemporary to Pucllana. Approx 200-600. This and other tourism websites bear witness to the pulling power of the three H’s: history, heritage and historiography (in short: When, Wow and How). For historians and the Peruvian travel industry this is cheering news as other country-destinations fight over the promotion of the S’s: sun, sand, sea, surfing, sailing. At one time it was S’s in the north and H’s in the south of Peru. But no longer, now that the Moche circuit is on stream. Below, the larger vessel in the Pucllana site museum carries the characteristic killer whale or shark, confirming the importance of the maritime economy to the people of the Lima culture and of Pucllana itself, from which you can see the sea – just.

Pucllana research

It is to be hoped that the ongoing excavations at Pucllana will be able to throw further light on the issue of the intermediary as well as the intermediate status of the Lima culture. Pucllana has one of the strongest research teams, thanks in part to support from the Municipalidad de Miraflores. The team comprises the Dirección del Proyecto Arqueológico: Isabel Flores Espinoza, plus specialists in the areas of Secretaría (one), Research (six), Conservation and restoration (two), Logistics (one), Administration (two), and Cultural Promotion (four): a strength of specialists unusual in Peru outside the big internationally funded “glamour” projects.

The Moche Valleys a state?

The jury is out on whether the Moche Valleys (right) constituted a state. The main ceremonial and administrative centre is taken to be on the Moche River at the Huacas de Moche. Present day Trujillo is just across the valley to the north, and the present-day resort of Huanchaco and port of Salaverry are not far away. Since the excavation of Sipán (by Walter Alva, 1987), a wider vision of the Moche has been evolving and a northern Peru tourist circuit has become a reality based on the Ruta Moche.

The jury is out on whether the Moche Valleys (right) constituted a state. The main ceremonial and administrative centre is taken to be on the Moche River at the Huacas de Moche. Present day Trujillo is just across the valley to the north, and the present-day resort of Huanchaco and port of Salaverry are not far away. Since the excavation of Sipán (by Walter Alva, 1987), a wider vision of the Moche has been evolving and a northern Peru tourist circuit has become a reality based on the Ruta Moche.

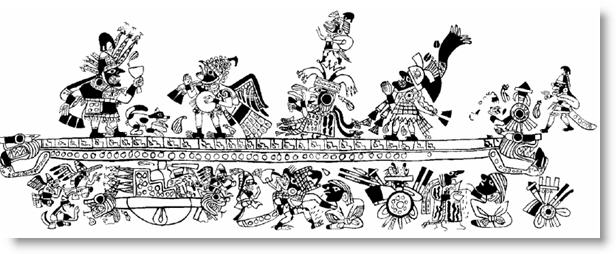

This map greeted visitors to the Moche exhibition at the Quai Branly Museum near the Eiffel Tower in Paris. Titled “Sex, Death and Sacrifice in the Mochica Religion,” some have said the exhibition is bad for Peru’s image abroad, unlike the earlier Paracas exhibition at the same Museum.

Image and reality

In the process of analysis and assessment of the Moche culture a lot depends on the ability to disentangle myth from reality – in a sense fact from fiction. Are the images below of real events, for example of actual bloodletting, prisoner-sacrifice etc, or do they portray mythical divinities performing rituals?  Similar Similar fine-line images intrigued the record number of visitors to the 2010 Moche exhibition in Paris.

Similar Similar fine-line images intrigued the record number of visitors to the 2010 Moche exhibition in Paris.

Nasca genius – contrasting solutions

Although there was contact and exchange between both the Moche and Nasca cultures, they seem to have developed quite independently [4], resulting sometimes in contrasting solutions (left) to environmental, social and economic challenges.This spiral pathway leads down to a system of underground aqueducts, tunnels and irrigation canals known as puquios[5]. This system is better adapted to the extreme drought conditions of the Nasca area of southern Peru. The Moche area, by contrast, has comparatively more mountain-sourced rivers crossing the dry coastal pampa. Conventional irrigation canals – acequias – were a more appropriate solution for the Moche.

Although there was contact and exchange between both the Moche and Nasca cultures, they seem to have developed quite independently [4], resulting sometimes in contrasting solutions (left) to environmental, social and economic challenges.This spiral pathway leads down to a system of underground aqueducts, tunnels and irrigation canals known as puquios[5]. This system is better adapted to the extreme drought conditions of the Nasca area of southern Peru. The Moche area, by contrast, has comparatively more mountain-sourced rivers crossing the dry coastal pampa. Conventional irrigation canals – acequias – were a more appropriate solution for the Moche.

Round-up

In the previous part of this series the museum at Huallamarca gave us a glimpse of a society in transition about 2000 years ago. The fourth site visited in our time-tour (sites and museums visited chronologically) is Pucllana – the Huaca Juliana in Miraflores, Lima (See also Part 2 and Part 3 for location and other details). It was built and occupied around the time (200 AD) that Huallamarca was closing down for its regular punters, and converting to an asylum for the dead. Pucllana is currently being actively excavated by a team under the long-serving archaeologist Isabel Flores Espinoza. Today the municipalidad of Miraflores as well as the INC supports the project which is generally regarded with some pride. On an average day many of the visitors to the site may be from abroad or from local school groups. Pucllana is also used as a cultural backdrop for fashion shows and other events ranked socially prestigious. Soon writers will be calling the site iconic. Ironic – considering Jimenez Borja’s one-man uphill task fighting the huaca bulldozers in the 50’s and 60’s.

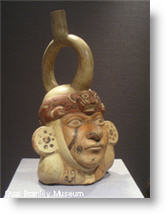

Pucllana is symbolic of an extraordinarily creative period in Peruvian history that is best known through the everyday ceramic imagery and portraits of the Moche (north of Lima – image left) and Nasca (south of Lima), and through weavings and embroidery of a “world-class quality” following on from the classic period of the Paracas-style (for example. from 300 BC). The economy was becoming more specialized with some early aspects of mass-production (including ceramics from molds and vertical specialization in weaving).

Pucllana is symbolic of an extraordinarily creative period in Peruvian history that is best known through the everyday ceramic imagery and portraits of the Moche (north of Lima – image left) and Nasca (south of Lima), and through weavings and embroidery of a “world-class quality” following on from the classic period of the Paracas-style (for example. from 300 BC). The economy was becoming more specialized with some early aspects of mass-production (including ceramics from molds and vertical specialization in weaving).

How, though, do we explain the relatively low profile of the Lima Culture or Style – wedged as it was between the two cultural giants of the Moche and the Nasca. Surely Pucllana, Maranga and the other Lima areas could have assimilated the best of both the better-known neighbors and triumphed?

Incidentally

- In terms of European history, Pucllana held sway around the time the Romans were retreating and the Saxons came to take over a small and hitherto unremarkable island called Britain, whilst the period for “Pucllana under the Huari empire”- say 700-900 – coincided with the Vikings “ravaging” the coasts of Europe and the expansion of Charlemagne’s empire.

- Sacrilege or sanity? Pucllana has – on top of its tourist revenue – boosted its income by hiring out the site as a heritage backdrop for fashion shows, theatre and musical opera. Part of the site houses a high-class restaurant. The history of using archaeological sites to confer legacy goes back to at least Jiménez Borja, who located the display of his collection of authentic Peruvian costumes at Puruchuco. See Looking Back –“Festival of native music and dances” by P. Massey, published in the Peruvian Times in 1967.

NEXT PART: In the next several parts we will be examining the idea that it was this “early intermediate” period – without detracting from the importance of the later “Inca horizon” – which lays a strong base for Peruvian identity and we continue the search for the “paradigm shifts” that occurred during this period. Each of the main areas of artistic and technological change is examined in turn: architecture, ceramics, textiles, writing and water.

____________________________________

![]() Technical tip: transparent evidence. You can have quick peeks at the contents of underlined or highlighted links (references, citations with content) without leaving this page, by installing Coolpreview or a similar application. As a reader of repotted history, you have a right of access to the document, media or object which is used to justify the sometimes outrageous assertion of the historian. (You may have to start using a Firefox browser).

Technical tip: transparent evidence. You can have quick peeks at the contents of underlined or highlighted links (references, citations with content) without leaving this page, by installing Coolpreview or a similar application. As a reader of repotted history, you have a right of access to the document, media or object which is used to justify the sometimes outrageous assertion of the historian. (You may have to start using a Firefox browser).

____________________________________________________

[1] A chance to explore the hypothesis of a “Kuhnian technological or, perhaps, paradigm shift” or more simply a pun on the influence of the sea on the coastal cultures?

[2] Referring to the influence of Nasca on the Rimac (Lima) valley: “The discovery of these specimens extends the northern limit of late Nasca influence—which hitherto was only documented as far as the Cañete valley—to the Rimac valley. It is difficult to speculate to what phenomenon this influence can be attributed. It may be a first manifestation of the inter-regional contacts which characterizes the early Middle Horizon. But the figurines are certainly not imports; they are even too different from late Nasca prototypes (both in appearance and in manufacturing techniques) to have been manufactured by Nasca. . . “ [Morgan, A. see Zotero]

[3] In-between cultures, states and nations can sometimes profit from dynamic neighbors or sometimes be dragged down or overwhelmed by them. Think Korea in-between China, Japan, Russia. What was it in the case of the Lima / central coastal area? Influenced by the powerful pottery from the Moche to the north and the tempting textiles from the Nasca to the south, there was trade and exchange or at any rate cultural influence (some – see also Morgan A. PhD dissertation). Perhaps the Central Coasters were the intermediaries, the traders and the navigators?

[4] The Moche occupied several different valleys along the north coast between 200 and 800 AD. During approximately the same period, the Nazca established themselves in the valleys along the south coast. Although there was contact and exchange between both cultures, they also developed completely independently and some of their results showed opposing systems. Both cultural formations adapted well to their coastal environment, using marine and land-based resources and developing agriculture that included complex irrigation works. However, there more rivers in the north and the water management extended over broader expanses. This did not mean that the Nazca were lesser farmers and hydraulic engineers –to the contrary, the Nazca developed very ingenious systems to control the scarce amount of water available in their region, recovering water from underground rivers and bringing it to the surface. (Quoted from Moche-Nasca, Sucedió en el Perú)

[5] There are of course places named Puquio, which presumably have or had the source of water supply nearby. Notably the Puquio of Arguedas on the road to Andahuaylas from Nazca.

_____________________________________________

Zotero bibliography | PBS films on Peru | LANIC-Peru | BBC History of the World podcasts | Evolving articles | Study/Research Peru SAS-ISA | Wikipedia articles on Peru | Other (OA) open access | OA Archaeology |

__________________________