Published in The Lima Times* November 28, 1975

In 1900 BC less than 2,000 people lived in the lower Chillón Valley to the north of Lima. But for this ancient era, several centuries before the invention of pottery, such a figure could be considered a sizable coastal valley population, for many Andeans still led a simple, nomadic existence, migrating from one temporary settlement to another in search of the seasonal foodstuffs available in several different ecological zones.

One of these early settlements, tucked safely away in the hollow of a large, horseshoe-shaped hill, seems to have prospered more than any village or hunting camp to the north or south. At this site called Chuquitanta or El Paraíso, just a mile from the ocean, prehistoric man had already outgrown his traditional pattern of seasonal hunting and gathering, and settled down to a sedentary way of life based on farming. Here French archaeologist Fréderic Engel, with the help of the Agrarian University at La Molina, excavated and restored part of what may have been the most important pre-ceramic architectural complex in the entire valley.

One of these early settlements, tucked safely away in the hollow of a large, horseshoe-shaped hill, seems to have prospered more than any village or hunting camp to the north or south. At this site called Chuquitanta or El Paraíso, just a mile from the ocean, prehistoric man had already outgrown his traditional pattern of seasonal hunting and gathering, and settled down to a sedentary way of life based on farming. Here French archaeologist Fréderic Engel, with the help of the Agrarian University at La Molina, excavated and restored part of what may have been the most important pre-ceramic architectural complex in the entire valley.

Population estimates for the site reach nearly 1500 persons, that is, more than three-fourths of the population of the entire Chillón Valley during this period. With the construction of Chuquitanta –possibly the first ceremonial center and perhaps the first true city in the Andes –the people of the central coast were certainly standing upon the threshhold of civilization.

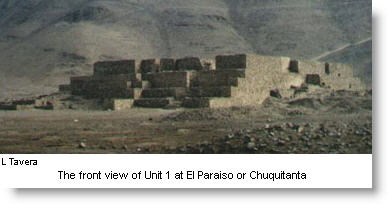

Most of Engel’s work was concentrated in an area termed Unit I. Although actually one of the smaller mounds (the entire site comprises some 900 by 700 square meters and includes eight major mounds), this restored unit is an impressive edifice composed of a series of rectangular, truncated platforms measuring approximately 50 meters square. The principal construction material at the site is angular rock cemented together with mud mortar. Evidence of a heavy clay coating on some of the preserved wall surfaces show that the coarse stone walls were plastered and perhaps even painted.

According to Engel, five or six successive construction stages were revealed in excavation. Apparently each of these phases consists of a group of interconnected rooms, passageways and open courtyards or patios, which succeeding occupants filled in with coarse stone and earth to provide the floor for the next building stage. As a result, the present reconstruction of the last building phase at the site is a relatively high huaca that is entered by a set of steep, narrow stairs leading to the central portion of Unit I.

According to Engel, five or six successive construction stages were revealed in excavation. Apparently each of these phases consists of a group of interconnected rooms, passageways and open courtyards or patios, which succeeding occupants filled in with coarse stone and earth to provide the floor for the next building stage. As a result, the present reconstruction of the last building phase at the site is a relatively high huaca that is entered by a set of steep, narrow stairs leading to the central portion of Unit I.

Engel cleared and restored about two dozen rooms and patios which he thinks once constituted the last stage of occupation. However, a close look at the relationship between the central area and the large, flanking wings to the east and west suggests that more than one building phase is represented in the restoration: that the floor of the central section is lower than those of the adjacent rooms, and that the pattern of abutting platforms and walls around the perimeter of the central sector proves that these protions were added later. In any case, the size and the complexity of its internal divisions are truly remarkable for this early epoch in Peruvian prehistory.

Variation in the size and arrangement of the rooms and patios within distinct sectors indicates that multiple functions were carried out in Unit I as a whole. The largest room or courtyard, located in the northeast corner at the top of the main staircase, seems to have fulfilled civic or religious functions. The exposed floor area here has four circular stone pits at the corners of a large, rectangular stone-lined terrace.

Other sectors within the unit are primarily made up of smaller rooms guarded by narrow or “baffled” entrances. These more modest rooms probably served as the loci of domestic activities; here the servants or guardians of the temple or ceremonial structure labored and slept, as well as cooked and ate, tossing the remains of their meals into the corners of the rooms where large accumulations of “middens” built up over the years of intensive occupation.

The inhabitants of Chuquitanta no doubt were farmers who had evolved subsistence patterns based on river-edge agriculture along the flood plain of the Chillón River. The location of the site was certainly not a random choice: a relatively wide margin of arable land, combined with a year-round water supply and a protected settlement area were conditions that not only supported its growth, but also engendered a significant trade in foodstuffs.

Large quantities of shellfish remains in many areas of the site’s extensive habitation indicate that marine foods –an important source of protein– were available. It seems likely, furthermore, that trade in marine and agricultural products existed between Chuquitanta and sites both along the coast (at Ventanilla and Ancon) and possibly farther inland up the valley. Some of the food remains recovered by Engel were squash, beans, pacae, lucuma, shellfish, sea lion, fish and deer bones. Corn had not yet appeared, nor had ceramics or metal artifacts, but twined, as well as true, loom-made, fabrics were found.

Large quantities of shellfish remains in many areas of the site’s extensive habitation indicate that marine foods –an important source of protein– were available. It seems likely, furthermore, that trade in marine and agricultural products existed between Chuquitanta and sites both along the coast (at Ventanilla and Ancon) and possibly farther inland up the valley. Some of the food remains recovered by Engel were squash, beans, pacae, lucuma, shellfish, sea lion, fish and deer bones. Corn had not yet appeared, nor had ceramics or metal artifacts, but twined, as well as true, loom-made, fabrics were found.

The presence of such varied types of midden remains seems to point up that an exchange system bound together for the first time several regional groups or economies exploiting widely different ecological situations. In this way a greater variety and quantity of foodstuffs were available throughout a large area that, by 400 AD, was able to support 30- to 40,000 people.