Over the weekend, Peru’s leading op-ed columnists continued to criticize President Alan Garcia’s decision to reject a $2 million donation from the German government to build a museum to honor the memory of 70,000 people who died as a result of Peru’s 1980-2000 civil war.

The criticism prompted President García to admit that the successive governments in the 20-year struggle commited “terrible abuses” but questioned the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report and said that Germany’s proposal for a museum did not “reflect the national vision.”

Educator Leon Trahtemberg titled his column “From damaged memory to lacerated future”, while analyst Raul Wiener recalls that “the same government that wanted to organize the 2006 Olympic Games considers it almost a frivolity to use a foreign donation to build a Memorial Museum.”

“The intention of memorial museums is not to confront but to unite,” said Pepi Patron in La Republica’s Sunday supplement, remarking on the irony that two gifts from Berlin have been given such opposite responses: rejection to one for building a memorial museum, and proud celebration of the other, the Golden Bear award from the Berlin film festival, won by the Peruvian film Milk of Sorrow, which deals precisely with the violence against Andean women during the 20 years that Peru struggled against Shining Path insurgents.

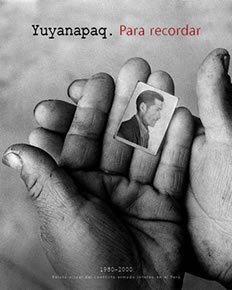

The donation from Germany was offered after a visit made last year by the German minister for Economic Cooperation and Development, Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul, to the Yuyanapaq exhibition, a photographic history of the 20-year war that is housed temporarily in the Museum of the Nation. The donation would apparently be managed primarily by the Ombudsman’s office.

The donation from Germany was offered after a visit made last year by the German minister for Economic Cooperation and Development, Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul, to the Yuyanapaq exhibition, a photographic history of the 20-year war that is housed temporarily in the Museum of the Nation. The donation would apparently be managed primarily by the Ombudsman’s office.

Though Garcia’s government did not at first respond officially to Germany’s offer, it has since suggested using the funds to tackle poverty and health care issues.

“If I have people who want to go to the museum but they don’t eat,” said Defense Minister Ántero Flores-Aráoz, “they will die from starvation. There are priorities.”

Later, Premier Yehude Simon suggested that the funds – rather than be spent on a museum – could go toward reparations for the victims of the political violence and military repression.

“Peru hasn’t rejected the money,” said Simon, “and if Germany agrees, we can receive it. We are very grateful, but we think that the money should be allocated to the victims of violence. That is the answer.”

The government’s decision has generated criticism from a wide spectrum of civil society, including artists, human rights and labor groups as well as intellectuals, such as Peru’s leading literary figure, Mario Vargas Llosa, painter Fernando de Szyszlo, and Liberation Theology leader Gustavo Gutierrez, who are reportedly circulating a petition criticizing the government’s position.

“Unity within a nation is consolidated via equality, liberty and justice and not with intolerance, hatred and injustice,” said Peru’s Ombudswoman, Beatriz Merino. “From this basic and unquestionable premise comes the need for truth, people need to learn about themselves through truth, and from there comes the international trend to build memorial museums.”

“I, as Ombudswoman, urge the government to reconsider its decision and accept Germany’s generous donation.”

“The word and attitude of politicians – and this is confirmed in all polls – is completely devalued,” said the former president of Peru’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, CVR, and former rector of Lima’s Catholic University, Salomón Lerner. “What credibility do our country’s politicians have? Obviously, they’re going to turn against the idea (of building a memorial musem), but they unfortunately no longer represent those who elected them, and have turned into small concentrations of power.”

The museum will not open new wounds, Lerner added, because they are “still open. I can’t find a single reason to reject this donation.”

Five years after Peru’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission issued its report on two decades of political violence that left nearly 70,000 people dead, the nation is far from reconciled.

The commission produced its nine-volume, 5,000-page final report in August 2003, after collecting 17,000 private and public testimonies, some aired in 14 public hearings. The report determined that 54 percent of all deaths in the conflict were caused by the Maoist Shining Path insurgency. Peru’s armed forces were blamed for 30 percent, and most of the remainder by government-backed peasant militias.

Eighty-five percent of the victims were poor, Quechua-speaking Indians from the Ayacucho region and five other departments in Peru’s Andean highlands, a fact that the CVR report noted was proof of the country’s continuing exclusion and rejection of Andean peasants and their communities and traditions.

The government has failed to follow through with reparations to the families of victims or to exhume bodies from mass graves identified in the CVR report — a job that has fallen in large part to the independent Peruvian Forensic Anthropology Team, a non-profit NGO. Human rights groups estimate that approximately 14,000 disappeared persons are still unaccounted for, and that nearly 5,000 clandestine graves have yet to be excavated.

The work of Peru’s Truth Commission is similar to experiences since the 1980s in South Africa and in other Latin American countries such as El Salvador, Guatemala, Chile, and Argentina, which popularized the famous slogan Nunca Más or “never again.”

Peru’s Truth Commission was created in 2001 by interim President Valentin Paniagua, months after Fujimori fled to Japan and his 10-year authoritarian government collapsed under the weight of corruption scandals spawned by his shadowy intelligence chief, Vladimiro Montesinos.

The Commission’s report has never been accepted by the military nor by the political parties who governed the country during the 20-year war, namely Accion Popular (the Belaunde government), APRA during President Garcia’s first administration, and supporters of President Fujimori, who is currently on trial for human rights abuses committed during the latter years of the war. And although priests and religious leaders at grassroots level were witnesses to many of the events, Cardinal Luis Cipriani, whose own position during his time as Bishop of Ayacucho was severely questioned by human rights groups, has rejected the report outright on numerous occasions.

Part of the CVR’s work included the production of an exceptional photographic exhibition documenting Peru’s civil war. Titled “Yuyanapaq, to Remember,” the photographs, audios, videos and timelines depict events and stories to explain – and remember – the evolution of the war, massacres such as those of Uchuraccay, Pucayacu, Socos, Accomarca, and Lucanamarca, as well as the murder of social activist Maria Elena Moyano by the Shining Path, the Barrios Altos killings by a paramilitary death squad, the attack against the Tarata building in upscale Miraflores, the Chavín de Huantar military rescue operation, and the impact of violence in universities across Peru, in the central jungle, Raucana, Huaycán and the department of San Martín. The photographs were selected from the archives of leading news photographers and journalists who covered the war. The exhibition was housed at the Catholic University’s facilities in Chorrillos for the first year, and moved to the Museum of the Nation.