Peruvian journalists across Peru held marches and commemoration ceremonies on Monday to honor eight journalists that were murdered 26 years ago in the Andean hamlet of Uchuraccay, Ayacucho. At the same time, the victims’ families demanded that the case be reopened.

“So that it never happens again, Uchuraccay martyrs never again!” chanted marchers in Juliaca, who walked from the Zarumilla plaza to the city’s cemetery.

“The Uchuraccay case must be reopened because neither the (victims’) family members nor the Peruvian Journalist Association were satisfied with the conclusions drawn by the investigative commission (led by Peruvian writer Mario) Vargas Llosa,” said Zuliana Lainez, secretary general of Peru’s National Journalist Association, ANPS.

“If nothing is done,” Lainez siad, “we will take the case to the Inter-American Human Rights Court.”

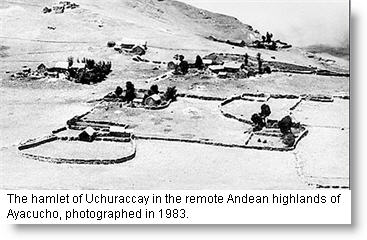

On Jan. 26, 1983, eight journalists, most of them from Lima, and their guide, Juan Argumedo, set out for the rural community of Uchuraccay. They traveled high into the remote and sparsley populated areas of the Andes in Ayacucho, to report on the increasing violence and alleged human rights abuses.

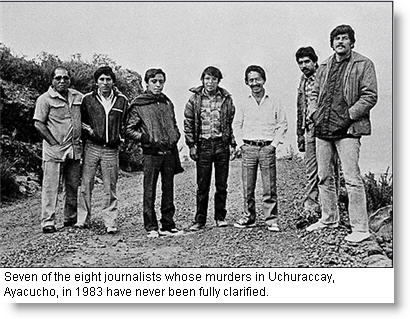

Upon their arrival, in uncertain circumstances, the eight journalists and their guide were attacked and murdered with machetes and axes. Jorge Sedano, Eduardo de la Piniella, Willy Retto, Pedro Sánchez-Gavidia, Amador García, Jorge Luis Mendivil, Félix Gavilán, and Octavio Infante were then buried in shallow graves by Uchuraccay residents.

A commission headed by Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa determined that the Uchuraccay indigenous peasants – mistaking cameras for weapons and the reporters for guerrillas – killed the journalists and their guide. Some critics believe the generic accusation of “barbarism, savagery” by long-forgotten and long-ignored peasants was a solution to avoid broaching possible accusations on the military.

Some more extreme analysts were willing to believe that the murders were carried out by military troops dressed as peasants, but according to the human rights organization APRODEH, the peasants -who were visited only a couple of days earlier by a contingent of marine infantry- most probably acted out of fear on the most recent military orders that “friends arrive by air (military helicopters), enemies come by land.”

Several months later, a camera belonging to Retto was discovered near the village. The reasonably well-preserved film revealed photographs taken just minutes before his death, in which the reporters can be seen talking with the peasants. The new evidence undermined some of the hypotheses about the killings, but the truth remains unknown.

Eventually, three peasants were charged with murder. Witnesses mysteriously died during and even long after the trial and the peasants charged with the crime, Dionisio Morales, Simeon Aucatoma and Manuel Ccsani, were found guilty in 1987 and sentenced to between six and 10 years in prison, to be served in Lima. One of the prisoners died of tuberculosis in prison.

In 1980, the Communist Party of Peru refused to take part in the democratic general elections and its extreme faction, Sendero Luminoso or Shining Path, launched a guerrilla war against the government. By 1982, its armed wing, the People’s Guerrilla Army, was formed and active, especially in the Ayacucho region, where it had its strongest base. The government turned the battle over to the military after the first 18 months of increased police and national guard patrols proved unsuccessful.

While many atrocities were attributed to the military, others were carried out by Sendero as acts of punishment for presumed peasant collaboration with the government. Hundreds of Ayacucho townspeople and peasants from neighboring villages were executed, sometimes as part of “people’s trials,” and the villagers lived in permanent fear of having their children taken away by the guerrillas.

The military, building on counter-insurgency policies and anti-Communist doctrine, also targeted the civilian population and popular organizations from which they mistakenly believed the Shining Path drew its support. At the time, General Clemente Noel, the officer in charge of the zone, openly advocated a scorched earth, no-prisoners policy.

Quechua-speaking peasants – such as those in Uchuraccay – were especially targeted, and were also strongly encouraged by the military to practice self-defense.

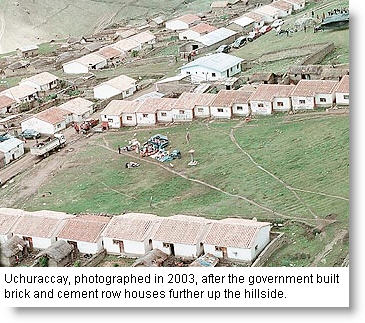

Caught between two “armies,” Uchuraccay was completely deserted by 1984, just one year after the massacre.

Peru’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission determined that 54 percent of all deaths in the conflict were caused by the Maoist Shining Path insurgency. Peru’s armed forces were blamed for 30 percent, and most of the rest by government-backed peasant militias.

Eighty-five percent of the victims were poor Quechua-speaking Indians from the Ayacucho region and five other departments in Peru’s Andean highlands.