By Poppy Tollemache

✐ Peruvian Times Contributing Writer ☄

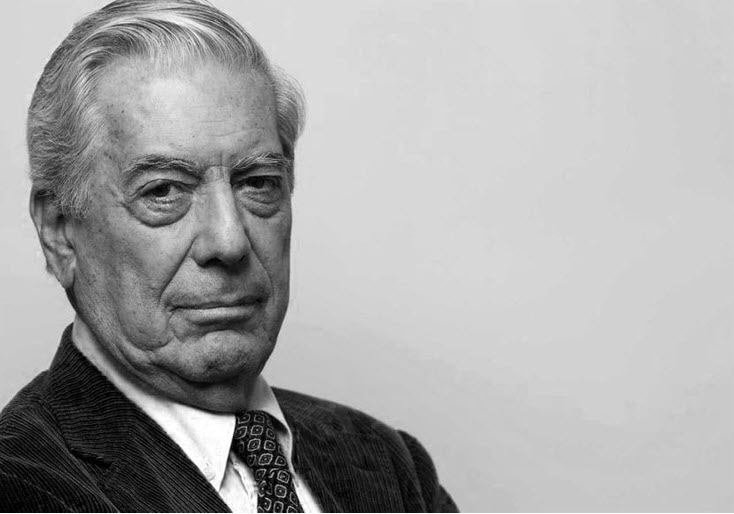

Nearly two months have passed since Mario Vargas Llosa, Peru’s most acclaimed novelist and a defining figure of Latin American literature, died at age 89 on April 13, 2025.

His passing marks the end of his remarkable literary era. With more than 50 books to his name, as well as essays, plays and journalism, Vargas Llosa was one of Latin America’s most evocative literary voices. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2010 for what the Swedish Academy described as “his cartography of structures of power and his trenchant images of the individual’s resistance, revolt, and defeat.” In 2011, Spain’s King Juan Carlos I created the Marquisate of Vargas Llosa, with the noble title of marquis, in recognition of his contribution to Spanish and world literature. And in 2023, he was incorporated into the Académie Francaise, France’s national linguistic watchdog. He was the first member of the institution to have never written a book in French.

As the initial tributes quiet and reflection deepens, Vargas Llosa’s legacy is being reassessed — both for his towering literary achievements and his polarizing politics.

His literary critique of authoritarianism and violence earned him a central place in the Latin American Boom, a literary movement in the 1960s and 70s that gained the continent global recognition. Alongside writers like Gabriel García Márquez, he helped redefine what Latin American literature could be: experimental, political, and unflinchingly honest.

On news of his death, Peru’s President Dina Boluarte dedicated a recent social media post to Vargas Llosa, naming him “illustrious Peruvian of all time,” while the presidential office praised his “intellectual genius” on X and affirmed that his legacy would endure for generations to come.

While tributes have poured in from across the globe, Vargas Llosa’s passing has also reopened debate about the complicated legacy he leaves behind. Although celebrated as a renowned author, he was also a polarizing political voice.

The Rise of a Literary Giant

Though born in Arequipa in 1936, Vargas Llosa spent most his early childhood in Bolivia, where his grandfather served as the Peruvian consul. He later returned to Peru to finish his schooling in Lima at the Leoncio Prado Military Academy and later to attend the National University of San Marcos.His time at the Academy influenced his first novel, The Time of the Hero (original title: The City and the Dogs), published in 1963. The work searingly critiques the military’s brutality and toxic masculinity, as experienced at the Academy, causing scandal in Peru. However, the novel was lauded internationally, winning the Biblioteca Breve Prize and launching his career.

From there, Vargas Llosa became a central figure in the Latin American Boom amongst writers like Julio Cortázar, Carlos Fuentes, and Gabriel García Márquez. The movement involved a political and aesthetic effort to interrogate colonial legacies, social injustice, and tensions across the continent.

Vargas Llosa’s friendship with García Márquez, in particular, became legendary. Their falling out in 1976, after an infamous punch Vargas Llosa threw at García Márquez in Mexico City, has remained a topic of literary gossip for decades. The cause of the feud has never been revealed.

Among Vargas Llosa’s most celebrated novels are The Green House (1966), a tale of corruption in Peru’s jungle, and Conversation in the Cathedral (1969), an extensive critique of military dictatorship in Peru during the rule of Manuel A. Odría. Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter (1977) offers a more playful, semi-autobiographical story connected to his first marriage, while The Feast of the Goat (2000) returns to darker political territory, dissecting the brutal regime of Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic. His last novel, I Dedicate My Silence to You (2023) was published just two years ago — a tribute to Peruvian music, folklore and his ex-wife Patricia Llosa.

From Radical to Liberal

Vargas Llosa’s early sympathies lay with the left, and like many Latin American intellectuals of the mid-20th century, he was initially inspired by the Cuban Revolution in 1959, led by Fidel Castro. However, he quickly became disillusioned with Castro’s regime and, by the 1970s, had turned sharply against authoritarian socialism. Instead, he aligned himself with democratic liberalism. This shift left him at odds with many of Latin America’s literary elite and is speculated to be one of the reasons for his fall out with García Márquez.

After spending most of his life in Europe, between Madrid, Paris, and London, he decided to return to Peru in 1974 out of fear of losing touch with his country and his language. In 1990, Vargas Llosa ran for president of Peru, campaigning on a platform of free-market reform and democratic governance. His candidacy came at a time of deep economic crisis and rising violence from insurgent organizations like the Shining Path, a far-left guerilla group. But despite his international prestige, he lost the election to Alberto Fujimori, a political outsider who promised a more populist approach.

His defeat by the then-unknown Fujimori, who would go on to become a dictator, was both a personal and political blow. Some Peruvians admired Vargas Llosa’s commitment to democratic principles, others saw him as detached from the social realities of everyday life. His later criticism of Fujimori’s policies led to threats from the government to strip him of his Peruvian citizenship, which led him to seek Spanish citizenship. He wrote of his bitter experience in politics in his memoir A Fish in the Water (1993).

In the decades that followed, Vargas Llosa continued to write prolifically, while becoming an outspoken advocate for liberal democracy in Latin America and Europe. He remained a controversial figure, particularly as he increasingly supported right-leaning candidates in Peru and abroad, and criticized populist movements across the continent.

Later-Life Controversies

In his later years, Vargas Llosa’s name remained in the headlines as much for his personal life as for his literary output. After a long marriage to Patricia Llosa, his first cousin, with whom he had three children, he divorced in 2015 and entered a high-profile relationship with Spanish socialite Isabel Preysler, the mother of pop singer Enrique Iglesias. Their relationship featured heavily in tabloids in Spain and Latin America until their breakup in 2022, which was followed by Vargas Llosa’s return to his former family circle.

His personal life aside, many of his public statements stirred controversy. He was criticized for his claim in an article for the Spanish-language newspaper EL PAÍS that feminism “is literature’s strongest enemy.” While he championed individual freedom, his beliefs often struck younger readers as tone-deaf in a changing cultural landscape.

A Divided Legacy

What, then, is the legacy of Mario Vargas Llosa?

It is, perhaps fittingly, a divided one. He was a fierce defender of literary craft, insisting that fiction mattered politically, morally, and artistically. His novels radically exposed the dysfunction of global institutions such as the military, the church, the media. Yet, he was also politically out of step with many of the young people who continue to study his work.

Still, his influence is undeniable in Peru, which finds itself mourning both a man and a literary era. His children Álvaro, Gonzalo and Morgana declared in a public statement on X that, despite their sadness, they would “find comfort […] in the fact that he enjoyed a long, adventurous and fruitful life, and leaves behind him a body of work that will outlive him.”

He paved the way for generations of writers to confront uncomfortable truths in Latin America, to take literature seriously as a vehicle for national self-examination. And perhaps that is the real irony: a writer who spent decades challenging Peru’s politics and society is now seen as a key figure in shaping its national identity.