— By Nicholas Asheshov —

The Incas, living as they did at 3,000 m a.s.l., focused on the Sun’s capacity to provide more than warmth for their fertile, glacier-fed tropical valleys. They and their predecessors grasped, like the Egyptians and others, that the movements of the sun, moon, and stars could predict rain and temperatures.

Information, then as now, was power, not just military muscle. But the study and understanding of the sun and the stars gave the Andean peoples much more than a weather channel. They were able to reflect the orderliness and mathematical precision of the heavens into their own world. The unequalled exactitude of Inca stonework and their careful, magnificently engineered, imaginative landscaping of their mountain world was a statement of philosophical power on a Shakespearean scale. They would control the uncontrollable, the earthquakes, enemies, famine, and disease. Under the Inca there would be no apocalypse.

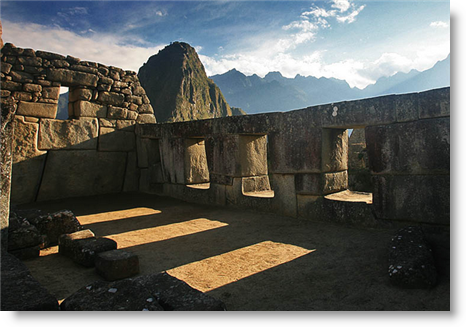

The Incas took it a logical step further. They would control the Sun itself. At Machu Picchu, Choquequirao, Pisac, and a score of other great centers, they placed carefully-engineered granite blocks and windows so finely that at the solstices —June 21 and December 21— needles of light would hit exactly at such-and-such a marker.

The Incas, like politicians through the ages, spun the Sun story. It was they who were family with the Sun, sons no less of the Sun. Running the universe had become a family business. The sun’s rays would change direction on the orders of the Inca every 187.5 days.

At the winter solstice, the Inti Raymi, visitors to Ollantaytambo today can climb high up to the other, western, escarpment of the Vilcanota River and, at 7 a.m. on and around June 21, can look down across the river half a kilometer away and watch a sudden sharp spotlight, then, moments later a couple of hundred yards away, another and then another appear on an Inca throne-room the size of a tennis court.

If this is a stirring experience today it is not difficult to imagine the awe, the grateful weeping, the roars of enthusiasm with which tens of thousands of Inca faithful would watch this mystic magic five, six and more centuries ago. They would see their Inca and his family re-born, the unchallengeable nexus of this world with the past and the future.

Accurate knowledge of how to interpret and predict stellar movements was a vital part of the management of a heavily populated agricultural society, for which control of irrigation water and of the rivers was essential in both drenching monsoons and periodic drought.

The Incas upgraded the Tiahuanaco and Huari terrace systems and roads into one of the world’s safest and most productive polities, as we can see today from a million terraces in great flights of ingenious engineering of one of the planet’s most spectacular sculpted landscapes. The renovations included unequalled mountain hydrologic and civil construction, together with agricultural and genetic research.

The magnificent interconnected terraces in the Colca, the Urubamba, Pisac and a score of other Andean valleys needed sophisticated agricultural techniques and engineering controlling water, heat, and experienced biological genetic experimentation. These terrace systems were so delicate that most of them are today unused because no one is sufficiently knowledgeable and well-organized to use them.

The incas also added to the pre-existing road system that runs across and up and down the Andes from Chile and Argentina to Colombia — a system of all-weather stone roads, with A, B and C grades, perhaps 15,000 miles in all. Armies, people and produce could move from one end to another as quickly and efficiently, rain or shine, as anywhere in the world until steamships and railways.

Today energy, not the Sun, has become the new god. It is energy, starting just two and a half centuries ago with the invention, in England, of the steam engine, that has created a different universe. Before 1750, no one moved faster than a horse, a running man, or a sail-driven galleon. Wood fires became coal, electricity, petroleum and nuclear.

A Bank of England economist calculated the other day that if we look at the 50,000 years of the existence of modern homo sapiens and call it 24 hours, 99% of the progress will have taken place in the last 20 seconds. It’s a nice notion though it might be seen to give a bit of short shrift to the Acropolis, to Leonardo and Bach. But it makes the point that few among the seven billion of us can understand the world today and for sure no one can control it. It is built to change. Intrinsically unstable. It must, faster and faster, keep on the move.

By contrast, anyone can see, at Machu Picchu and at Sacsayhuaman, that the people who built these achievements did indeed understand their universe. They had done it themselves, stone by careful stone. It was built never to change, to last forever. Maybe it will.

_____________________________

Nicholas Asheshov lives in Urubamba. A veteran journalist, noted explorer and entrepreneur, he was editor of the Peruvian Times from 1969 to 1990. This article was also published in Caretas magazine this week.

Pingback: What happens during Inti Raymi?