Commemorating Peru’s National Day 28 July and Arequipa’s 15 August 2020 was a rather sad FIESTAS PATRIAS this year, in view of the coronavirus pandemic.

By Paul Goulder —

By now Lima, if not the whole of Peru, should be in the grips of a bicentenary fever but as it is, a devastating global virus is occupying our attention. So instead, today we ask how the actual first centenary was commemorated and in which ways the Peru of 2021 can learn from the events of 100 years ago (even if we can bravely carry on, when and if the pandemic allows). Anniversaries provide opportunities to take stock and learn from the past.

I have based this article on and around a talk which was given at the launching in May 2016 of the book “Leguía, el Centenario y sus Monumentos. Lima: 1919-1930” by Johanna Hamann. The presentation took place in the Mario Vargas Llosa auditorium of the National Library (Biblioteca Nacional del Perú). Additional photos and other material come mainly from the 1921 Special Centenary Edition of the West Coast Leader, forerunner of the Peruvian Times. I am grateful to have had access to this, the main contemporary, anglophone source of reportage in Lima.

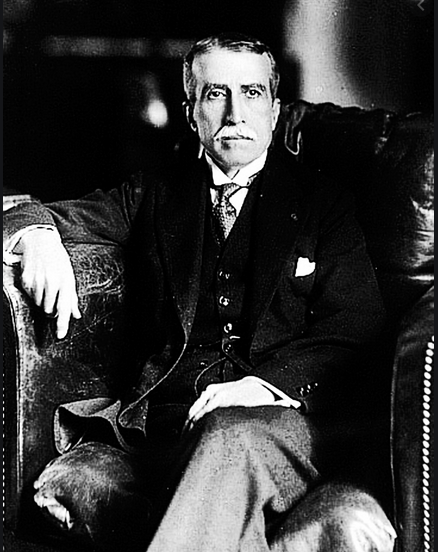

Leguía had grown up amidst the sugar hacienda power-brokers of Peru but his family was not from their ranks: his father was an administrator to plantation estates in the north of Peru. The politics of the country were dominated by the plantation aristocracy which came to be organized into the Civilista party. However, Leguía was sent away to a remarkable school in Chile — arguably the first business school in South America— and was beginning to understand Peru from a foreign vantage point at a time that Chile was preparing for war. Leguía returned home just in time to take part in the conflict which ensued. He was present during the Battle of Miraflores on 15 January 1881. He was 18 and not wounded and it is said that in the long walk home and following the personal and national humiliation of a Chilean invasion, he received the spark of inspiration that led eventually to the vision for a Patria Nueva – a new fatherland and a wildly ambitious set of Centenary celebrations.

The Patria Nueva had a physical, architectural dimension, which is partly explored below, and also a philosophical aspect in terms of political economy. Leguía lived in New York and London and favoured an anglo-saxon style, competitive & entrepreneurial rather than oligarchic economy, though many of his centenary projects were carried out by just one American corporation.

The centenary was to play a vital role in providing an excuse for conspicuous consumption and a target date for the completion of (some) projects. The foreign communities could be expected to deliver a proportion of the monuments which were necessary to “beautify” the new Lima.

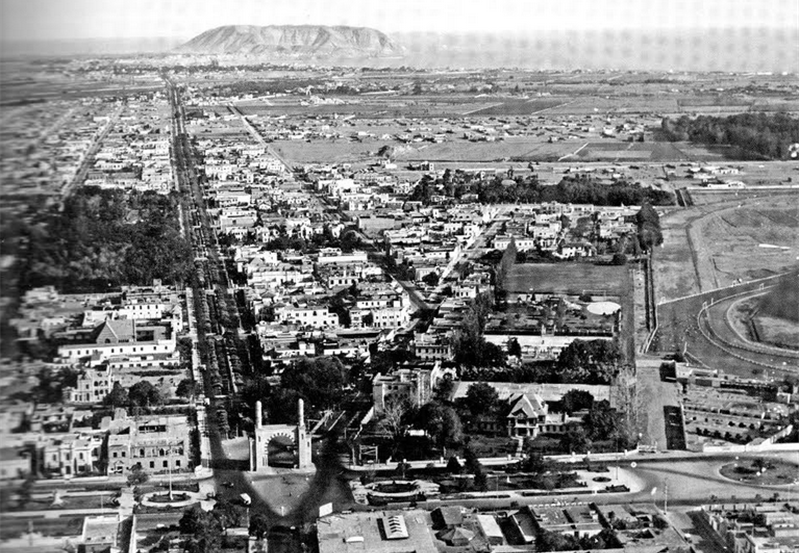

The Patria Nueva

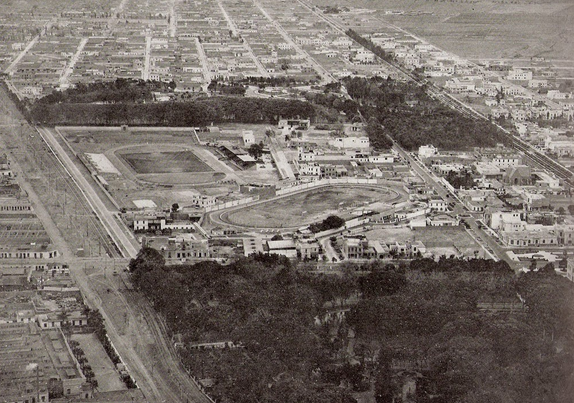

An aerial but partial view, above, of the “architectural realization” of Leguía’s Patria Nueva Lima, c.1929 — the area fanning out from the new Moorish Arch, a centenary gift from Spain (perhaps a rueful reflection on the 1821/25 independence from Spain and the 1492 reconquest of the Moors?). In the photo the parallel Avenidas Petit Thouars, Leguía (now Arequipa) and Arenales with Salaverry barely surveyed (alongside “Leguía’s” racecourse extreme right). Between the Moorish Arch and the racetrack lies the English-style Lawn Tennis Club. Av. Arequipa together with Jirón de la Unión and Wilson – a unifying axis running through the capital city – could be seen as Mexico City’s “La Reforma” for Lima.

It was the most beautiful road on the whole Pacific coast. And it was innovative for Peru. It was said that few properties in Lima had water supply and access to modern sewerage before Leguía. The houses on both sides of the road were individually designed for members of Lima’s new elite but little by little, over the decades, occupation changed to commercial use which some had argued was its “natural” urban function all along.

It was the most beautiful road on the whole Pacific coast. And it was innovative for Peru. It was said that few properties in Lima had water supply and access to modern sewerage before Leguía. The houses on both sides of the road were individually designed for members of Lima’s new elite but little by little, over the decades, occupation changed to commercial use which some had argued was its “natural” urban function all along.

There are still people living who remember being taken as children for a “sight-seeing” jaunt down the road, which had retained its elegance until the 1960s. Was it just a symbol of an extremely unequal society or had the architects achieved something quite remarkable where beauty overrides ostentation. Either way it did not last. The incentive was for commercial, education and institutional properties.

There are still people living who remember being taken as children for a “sight-seeing” jaunt down the road, which had retained its elegance until the 1960s. Was it just a symbol of an extremely unequal society or had the architects achieved something quite remarkable where beauty overrides ostentation. Either way it did not last. The incentive was for commercial, education and institutional properties.

However, though most of the original houses are now apartment blocks or commercial buildings, the avenue’s central walk remains and the entire 52 blocks are closed to traffic on Sunday mornings so that bikers and strollers can have free run of the space.

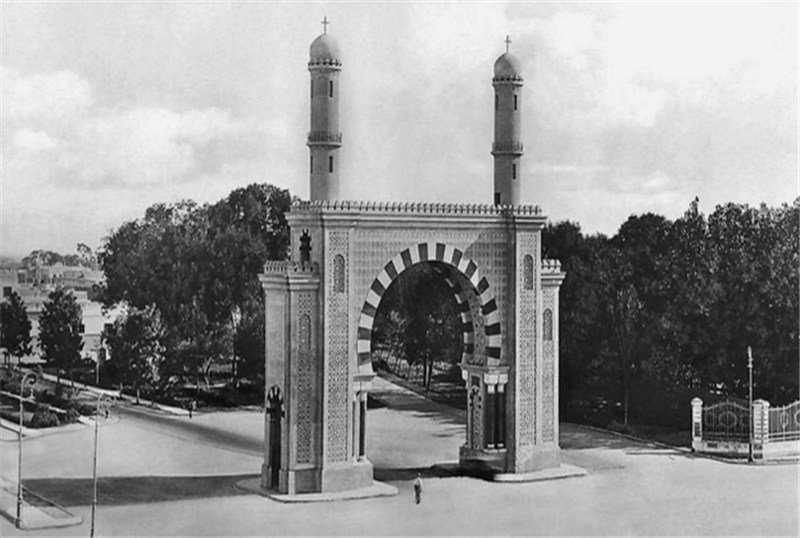

The Moorish Arch (right) was built at the commencement of Avenida Arequipa – gateway to the Patria Nueva ensanche or faubourg/immediate suburb of Santa Beatriz. Photo 1923. The arch was the centenary gift from the Spanish community in Lima. It was torn down in 1938/9 to make way for a traffic scheme. A somewhat incongruous replica was erected in Surco. If nothing else, it raises the question as to the meaning of centenary celebrations for previous colonial powers.

Vicinity of the city walls and Santa Beatriz

The Moorish arch given by the Spanish community stands just left of center in this aerial view of the Santa Beatriz area (above left), in the vicinity of: 2) the Stevedore sculpture, a gift from the Belgian community; 3) Joint Command of the Armed Forces; 4) Dog race track, now Parque Velarde; 5) Museo Metropolitano de Lima; 6. Parque de la Exposición; 7) Avenida Arequipa; 8) Av. Petit Thouars, with Colegio San Andrés one block further north; and 9) Av. 28 de Julio crosses the area, following the line of colonial city walls. The Stevedore sculpture (above right), by Belgian artist Constantin Meunier, has a supreme aesthetic quality.

The Italian Community and Italy

In 1921, Italy and the Italians in Peru gave the eye-catchingly beautiful Museo de Arte Italiano – complete with paintings and sculptures. It’s located on the Paseo de la República 250, Lima, near the Plaza Grau. (Initiated during the Italian Prime Ministership of Ivanoe Bonomi and the presidency of Augusto Bernardino Leguía, and delivered 1923-24.) The Latin American countries were important as destinations where émigrés from Italy could prosper. The Banco de Italia in Peru was one of the biggest and its director an important backer of the Museo de Arte Italiano project.

In 1921, Italy and the Italians in Peru gave the eye-catchingly beautiful Museo de Arte Italiano – complete with paintings and sculptures. It’s located on the Paseo de la República 250, Lima, near the Plaza Grau. (Initiated during the Italian Prime Ministership of Ivanoe Bonomi and the presidency of Augusto Bernardino Leguía, and delivered 1923-24.) The Latin American countries were important as destinations where émigrés from Italy could prosper. The Banco de Italia in Peru was one of the biggest and its director an important backer of the Museo de Arte Italiano project.

The United Kingdom

If the Italians had thought it suitable to give such an aesthetically fine reminder of their culture, the British apparently felt that for them their most significant contribution to the culture of Peru was in sport. Following independence, British sailors and traders, mainly, had introduced Lima to no less than cricket, polo, golf, rugby, football, ‘clubs’ generally . . . and dog racing:

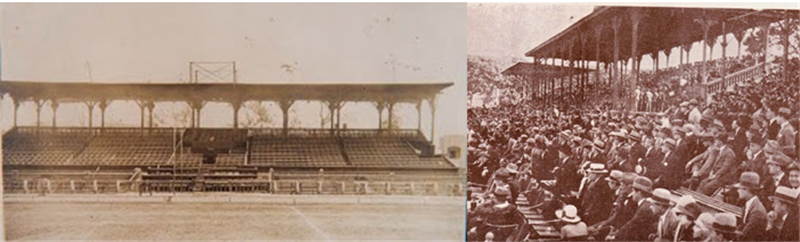

Three stadiums were given to Peru by the British Community. The football pitch in Santa Beatriz (above), which could seat 6,000 people and would become later the Estadio Nacional, and (right) the elliptical Dog Track – the Canódromo, closeby. Not shown: In Arequipa, the British community contributed to the stadium for the Melgar FC.

The dog track, sometimes thought to be the origin of the National Stadium (when initially viewing the aerial photo), was in fact for dogs and cycles! The track was used for only a few years, replaced in the 1930s by the Parque Velarde, a quiet tree-lined park surrounded by large homes.

The German Community

The German community presented Peru with a clock tower – constructed in front of the entrance to San Marcos University – reminding students to hurry along if they were late. However, for a time the campanile and clock were not well maintained and there were periods when neither clock nor chimes were on time. This photo shows the clock tower together with the statue of Sebastián Lorente – beloved nineteenth century educator (Guadalupe) and reformer (San Marcos). The grand modernist tower on the left was designed for the Education Ministry by Enrique Seoane, Peru’s first great internationalist architect.

A Gift from China and the Chinese Community

The Chinese community’s gift to Peru was a marble fountain to honor universal brotherhood (right), a beautiful monument made in Italy by Gaetano Moretti, who also designed the art museum donated by the Italian community. The fountain stands in the Parque de la Exposición, just a few steps from MALI, the Lima Art Museum.

There are several other gifts presented for the 1921 centennial, which we will include in an upcoming article, including two statues at Plaza Washington given by the United States, the French community’s “Statueof Liberty” in Plaza Francia, and the Japanese community’s statue of Manco Capac, now in La Victoria (see Leguía Centenario Monumentos and The Leguía Years 1908-1930)

What should we give for the 200th? The gifts of 1921.

What shall we, as Peruvians living abroad, as “Peruvians in the exterior / the Peruvian diaspora”, as non-Peruvians living in Peru or as friends of Peru generally, give to this magnificent country for its 200th anniversary in 2021? There are three to four million of us and if we all get together we should be able to make a big splash. Have a look at what was done 100 years ago. (And it does seem that that can be little guide to what we do in 2021, given the presence of the coronavirus pandemic.)

My gratitude for the help given by Johanna Hamann before her untimely death. Her book is essential reading for those planning bicentennial events.

Paul Goulder: Academic and specialist on Latin America and Peru, who has held academic posts at: ENSCP-Paris; King’s College, University of London; UNSA, Arequipa. He is also involved in not-for-profit work in ecology, development and education in UK and Peru.