By Poppy Tollemache ✐

Peruvian Times Contributing Writer ☄

Ayacucho, a culturally rich city in the Andes, is known for its 33 historic churches and extensive folk art industry.

Strategically located on the main Inca highway that once connected Cusco and Quito, the city has long served as a vital link in the Andean world. Today, Ayacucho hosts the largest Carnival and Semana Santa (Holy Week) celebrations in all of Peru.

This March and April 2025, an estimated 20,000 thousand visitors flocked to the city of to watch and take part in its spectacular festivities. With Peruvian government body PromPerú promoting the event with their social media campaign #CarnavaleaPerú, the events have surged in popularity and drawn even greater crowds than expected to the region, an increase of 10% over last year.

This growing influx of domestic and international tourists is transforming the city’s economy, bringing new opportunities for local artisans, businesses and cultural institutions. But it also raises important questions: how will Ayacucho balance tradition with commercial growth? Can the combination of festivity and religious devotion, so central to its Carnival and Semana Santa celebrations, be preserved as visitor numbers soar? Ayacucho now stands at a turning point: It wants to continue to encourage economic growth, without harm to its religious traditions.

Ayacucho’s Carnival

The Carnival, declared Cultural Heritage of the Nation by UNESCO in 2003, blends pre-Hispanic Andean rituals with Spanish colonial influences and local folklore.

Historically, the city was known as Huamanga during colonial times. It was renamed Ayacucho—Quechua for “corner of the dead”—after the pivotal Battle of Ayacucho in 1824, which took place in nearby Quinua. This battle is often regarded as the decisive victory that secured the end of Spanish colonial rule in Peru. The city’s pride in its symbolic role in Peru’s independence fuels the enthusiasm to make Carnival a celebration of pre-Hispanic rituals.

In the days leading up to Ash Wednesday, which this year was the first week of March, more than 200 dance groups, known as comparsas, paraded through the streets, dressed in handmade colourful outfits that reflect their different communities. They’re accompanied by the sounds of waqrapukus (Andean horns) and tinyas (drums), which play traditional folk-music. There are also rituals like the yunza, where people dance around a tree filled with gifts that is later cut down and shared, to celebrate fertility, unity, and reciprocity.

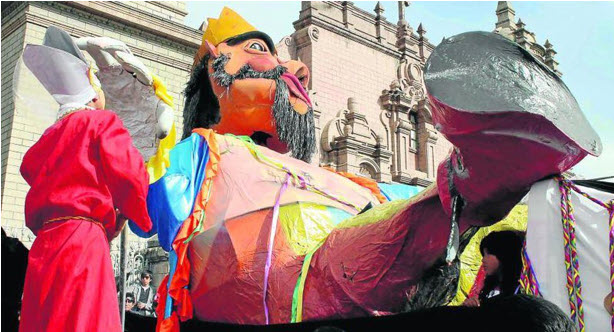

A satirical effigy called Ño Carnavalón—a large, cartoon-like figure made from papier-mâché that resembles King Momo from Greek mythology, symbolising satire and excess—is paraded through Ayacucho at the start of Carnival. The celebration ends with his burning, a symbolic act that marks the cleansing of indulgence before the solemn season of Lent begins.

Raúl Sayas, Ayacucho’s Minister of Culture, explains that traditions have survived largely because, “families continue to pass down customs and a deep connection to the past. Now, more young people are keen to join the comparsas and other customs.” This renewed interest not only keeps the culture alive but also reflects a strong desire to share it with the world through tourism.

#CarnavaleaPerú and Economic Growth

This year’s tourism boom was no accident. The launch of #CarnavaleaPerú was a national campaign under PromPerú’s Y Tú Qué Planes (‘And What Are Your Plans?’) platform, which promotes domestic travel. It focused on Ayacucho alongside Cajamarca, Apurímac, and Puno as key cultural destinations to celebrate Carnival.

Although the campaign ended before Semana Santa to preserve the festival’s more holy and reflective atmosphere, visitors continued to pour into the region to join in with the festivities in April.

Sayas acknowledges the success of PromPerú’s campaign in boosting domestic tourism but stresses the need to expand internationally: “It would be great to carry out tourism launches in Europe and the US and partner with world-class travel agencies, influencers, bloggers, and others.” He also warns that deteriorating infrastructure, especially the Via Libertadores Highway, is costing the region dearly: “According to experts, some 15,000 tourists leave or decide to go to other regions due to the poor condition of the roads,” leading to an estimated 50 million euros in losses each holiday, particularly for small businesses, hotels, restaurants, and farmers.

However, artisans, hoteliers and food vendors still reported a huge increase in sales this year. Sonia Huamán and her husband, who sew folkloric headdresses inspired by regional animals for Carnival and Semana Santa said: “This year we sold more than usual. Visitors want something meaningful, something made by hand that reflects our culture. And they respect it.” The surge in demand for these products indicates that tourism is supporting local artisans and businesses, while also encouraging cultural exchange and respect for traditional craftsmanship.

Melissa Torres Quispe, owner of Backpacker-Hostel Casa Kutimuy, noted that 2025 brought a much stronger turnout than the previous year: “Carnival season is about promoting culture and sharing experiences. But from an economic standpoint, particularly in lodging, the goal is also to reach at least 80% occupancy.” This year, she saw that goal exceeded, reporting that bookings rose from 60% to 80% between Carnival and Semana Santa.

While national campaigns have increased domestic visitors, poor infrastructure and limited international outreach remain major challenges. However, tourism in Ayacucho is still growing, boosting local businesses and cultural exchange.

Ayacucho’s Semana Santa

Semana Santa is the week leading up to Easter, which commemorates the passion and resurrection of Jesus Christ and is celebrated throughout Latin America.

Ayacucho’s Semana Santa involves 14 processions, starting on Palm Sunday and culminating on Easter morning. On Good Friday, locals spend the day making intricate carpets of flowers—decorative artwork made on the ground using colorful flower petals, leaves, sawdust, sand, or other natural materials. These intricate carpets are carefully arranged to form religious symbols, images of saints, or traditional patterns. At dusk, candlelit Señor de la Agonía processions pass through streets, walking over the flower carpets, destroying them in an act symbolic of Christ’s sacrifice. It is the most solemn day of Semana Santa, when Christ’s sacrifice is mourned.

On Holy Saturday, however, the mood transforms. After a week of lamentation, celebrations ensue. The celebrations start with jalatoro, or bull running, in which young men run through the streets, guiding bulls on ropes. Afterwards, brass bands, fireworks, horse racing and a frenzy of dancing ensues.

This contrast raises a question: does the influx of visitors for Saturday’s festivities distract from the sombre religious reflections during the previous week? For many locals, the two are inseparable. “There is no contradiction,” says Carolina Gavilán, a student from Ayacucho who helps make the floral carpets with her family. “The joy we feel on Saturday comes from our faith. If people come for the party and discover something more—that’s good. We welcome them.”

The celebrations culminate on Easter Sunday with the dawn procession of La Virgen de la Candelaria in front of Ayacucho’s cathedral. At 5 a.m., before the first light appears on the horizon, the Candelaria — a towering white pyramid lit with more than 2,000 candles — is carried out of the cathedral. Slowly, from the center of the glowing structure, the figure of Christ rises. Hundreds of devotees chant “¡Cristo ha resucitado!” (“Christ is risen!”) as the sculpture is paraded around the square until 7 a.m. It is a powerful and emotional finale to the week-long celebration.

Looking Ahead

While Ayacucho has made progress in attracting more visitors, poor infrastructure and limited international promotion still hinder its full tourism potential. Locals take deep pride in their culture and hope to see sustainable growth—not only to support livelihoods through crafts and small businesses, but also to share and preserve their traditions for a wider global audience. Ayacucho’s experience shows that tradition and tourism can coexist, and that economic development need not come at the cost of cultural authenticity.