An appreciation by Paul Goulder —

Máximo Damián Huamani, for long the doyen of Peru’s remarkable Andean violinists and friend of José María Arguedas, died on Thursday 12th February at the National Hospital Edgardo Rebagliati Martins. There followed the wake – in Máximo’s home and in the principal salon of the Ministry of Culture – at which mourners from the United States, Europe and from many parts of Peru participated. Following the funeral on Sunday 5th February at the Cementerio El Angel in old Lima, there was, for a week or more, a poignant series of meetings, conferences and concerts in homage to the violinist.

Máximo Damián Huamani, for long the doyen of Peru’s remarkable Andean violinists and friend of José María Arguedas, died on Thursday 12th February at the National Hospital Edgardo Rebagliati Martins. There followed the wake – in Máximo’s home and in the principal salon of the Ministry of Culture – at which mourners from the United States, Europe and from many parts of Peru participated. Following the funeral on Sunday 5th February at the Cementerio El Angel in old Lima, there was, for a week or more, a poignant series of meetings, conferences and concerts in homage to the violinist.

Damián’s story is that of a talented boy from Ayacucho who became, in the words of the La República newspaper, “the most respected folk musician of his generation.”

Máximo was born in the small Andean town of San Diego de Ishua, in the Aucara District of the province of Lucanas, Department of Ayacucho, Peru. His father Toribio Huamani was an itinerant master violinist who initially refused to teach Máximo to play the instrument – ambitious that his son should follow a more money-making profession.

However, the son persisted and his father then “taught him all that he knew.” Máximo finally played in public as a violinist around the age of 13.

Soon after, Máximo moved to Lima and took up work, of necessity, as a laborer, but nevertheless continued to play the violin. Weekends were often spent with those who had migrated from his area of the Andes, eventually catching the attention of author José María Arguedas, who was to become a good friend.

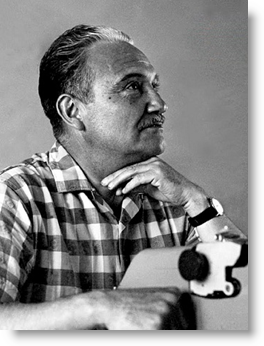

Born in Andahuaylas in 1911, Arguedas, beyond being a writer, was an anthropologist, poet, linguist, educator, journalist, and musician and a great promoter of Andean folklore. He helped develop the early Department of Anthropology at Lima’s San Marcos University and was the first Peruvian anthropologist to study aspects of Spanish life, comparing the villages of Leon y Castilla with those of the Andes.

With Arguedas’s help, Máximo was able to devote more time to music, playing in folk celebrations and participating in conferences on Andean culture. Through the Casa de la Cultura, he gave recitals in Venezuela, Brazil and Ecuador and later in Europe. Notably, Máximo and his three fellow artists (a harpist and two scissor danzantes) were chosen to represent Peru in a 1992 quincentenary concert in London.

We first met Máximo Damián on October 10, 1992 for that concert, when he and his three fellow artists were our house guests in London. They had been invited by a committee, chaired by Meriel Larken, that was organizing a special concert to be held at the Royal Albert Hall to mark the 500th anniversary of the famous 1492 event: Columbus landing in the “Indies” and Spain’s subsequent invasion [the Spanish Crown’s issuing of letters patent permitting the invasion] of the Americas, rebranded as the Encuentro. [i] Máximo’s Scissor Dancers had been chosen to represent Peru, performing amongst a star-studded cast drawn from the over 20 republics of the Americas.

José María Arguedas, who died in early December 1969, had expressed his wish that Máximo play at his funeral along with other – now famous – musicians: Jaime Guardia, Alejandro Vivanco and the Chiara brothers (and two other scissor dancers). They followed José María’s coffin in procession playing his favorite music. This became one of the pivotal moments in Maximo’s life for thereafter he became known as “Arguedas’ violinist.” This association with “JMA” was strengthened when Arguedas dedicated his last and posthumously published book “El zorro de arriba y el zorro de abajo” to Máximo Damián.[ii]

More recently it seemed that scarcely an important Arguedas-related event has been arranged without Máximo being requested to participate. On Friday a joint homage[iii] to both men was organized in the main conference hall of PetroPeru by Limagris.com. There appeared to be a seamlessness in the progression from one life to the other. Arguedas’s dramatic tragedy “La Agonia de Rasu Ñiti”[iv] is brought to mind and during the panel discussion, Luis Fernando Cueto credits both men with having introduced many non-Andeans to the “deeper, profounder” culture of Peru.

Kachkanirachmi – Sigo siendo

Years later, fulfilling the promise Máximo Damián had made to Arguedas, he continued to disseminate Peru’s traditional music: he traveled and played the violin worldwide and for this he gained recognition though often without much financial reward. In 1995, the National Institute of Culture awarded him the recognition of the Kuntur Medal and the National Engineering University decorated him for his contribution to folklore. In an impressive and moving ceremony, San Marcos University did likewise and in 2011 Máximo received the Arguedas Prize for his contribution to Peruvian music and his work as a leading Arguedianist.

In life he had many other decorations. In 2013, he participated in the documentary Sigo Siendo (Kachkaniraqmi, in Quechua) by director Javier Corcuera, a film that captures the music and lives of many of Peru’s greatest musicians with such dramatic and emotional effect that ‘grown men are reduced to tears’.

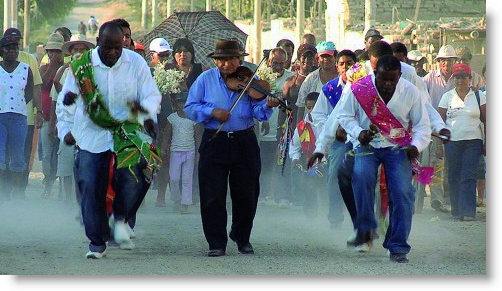

One of the most beautiful moments of the film occurs when Máximo Damián is seen playing his violin amid a procession in honor of the great zapateador[v] Amador Ballumbrosio. “That sequence[vi] is very special”, confessed once its director, Javier Corcuera. [See that footage on YouTube The sequence is 2.03 seconds into the trailer.]

Damián’s great support and professional partner in life was his wife, Ysabel Asto. Their Lima home was in San Miguel, though they would return to Ishua whenever possible, especially while Máximo’s mother was still alive.

It was his partnership with Ysabel that produced some of the most memorable music: the voice of this high-pitched “song-bird” matched perfectly the dazzling dynamics of the Andean fiddle playing; the duet was a masterpiece of harmony which sadly now cannot be heard again live. But you can listen to recordings of some of their repertoire on YouTube – the link to “Coca Quintucha” which Máximo Damián and Ysabel Asto have made virtually their anthem, as it was for the first Ayacucho migrants into Lima. A key verse goes as follows:

Panteón punkucha, fierro rejillas Panteón punkucha, fierro rejillas,

Punkuchaykita kichaykullaway Kuyasqay mamaywan tinkuy kunaypaq …

. . . Cementerio de rejas de fierro abre tus puertas para visitar a mi madre y encontrarme con mi padre.[vii]

And it is in the Cementerio El Angel that you can pay homage to both Máximo and José María[viii] at their grave-sides, scarcely 100 yards apart.

Máximo Damián should be remembered not only for his violin music but also his stalwart and stouthearted insistence on authenticity: he would reject financial offers to play more popular music, sticking to the less remunerative pieces which he had brought down from the Andes; and while many who migrated from the highlands would switch their language out of economic necessity from (in the case of San Diego de Ishua) Quechua to Spanish, Máximo would stick to the former whenever possible. Sometimes he would be met with the types of discrimination and racism characteristic of Lima: more so in the 1950s but even so today with newspapers reporting “difficulties” in his admission to hospital shortly before his death.

Historically, the span of years from 1935 —the date of publication of Arguedas’s first book, the collection of short stories “Agua” and the year in which Máximo Damián was born— through to the latter’s death, has seen a decidedly non-steady improvement in socioeconomic conditions for Andeans.

Just as Arguedas (see article here on his centennial) marked a sea change away from indigenista literature towards what is now called neo-indigenista or post-indigenista, so Máximo and his fellow musicians and dancers have been able to claim public space for Andean inspired culture. In 1950 Andean musicians would have been unwelcome on the streets of downtown Lima. Now Scissor Dance ensembles welcome foreign diplomats to the Palacio de Gobierno. But this improvement in esteem has been hard-won: there have been bad decades and not so bad times, but scarcely yet an age of enlightenment.

_______________________________________

Paul Goulder: Academic and specialist on Latin America and Peru. Last academic posts: ENSCP-Paris; King’s College, University of London; UNSA, Arequipa, Peru. He is also involved in not-for-profit work in ecology, development and education in UK and Peru. ______________________________

Footnotes

[i] Spain originally had launched the 1992 events as a celebration but upon protests from not just organizations representing the indigenous peoples of the Americas but also, for example, from some in the UK Parliament who could not quite see why Britain – historically Spain’s adversary in the process – should be celebrating or commemorating. The 500 year events were quickly rebranded as an Encuentro – a meeting of two cultures. This is one of the interpretations put forward by some Peruvian historians. Also known as “Europe becoming aware of the existence of the Americas”, but still generally referred to as the “discovery” of the Americas.

[ii] Translated as The Fox from Up Above and the Fox from Down Below by Frances Horning Barraclough, published by University of Pittsburgh Press, 2000.

[iii] The discussion panel comprised the writer Carlos Calderón Fajardo, the director of the “José María Arguedas” National Folklore School, Benjamín Loayza, note columnist Eloy Jáuregui, well-known author Luis Fernando Cueto, an the anthropologist Renatto Merino Solari, who spoke on the influence and presence of Arguedas in literatura, anthropologial research, music and folk.ore. Damián had been scheduled to perform at this meeting but with his sudden death the meeting was turned into a joint homage to Araguedas and Damian. See more at: http://www.limagris.com/homenaje-a-jose-maria-arguedas-y-maximo-damian-en-petroperu/#sthash.dGjtXRz8.dpuf

[iv] See Peruvian Times of 11/06/2011. https://www.peruviantimes.com/11/hidden-jewels-of-lima-la-agonia-de-rasu-niti/12675/

[v] Tap-dancer. Particularly in this case from Afro-Peruvian heritage, as distinct from the U.S. tradition.

[vi] “That sequence is very special . . . because Amador Ballumbrosio dances again, with the violin of Máximo Damián. . . . These identities of Peru also play and mingle, are mestizo, are not conservative, they meet, embrace.” Director, Javier Corcuera in translation. Quoted from La República Domingo, 15 February 2015.

[vii] A translation of Coca Quintucha is available on the Voces de Ayacucho website http://www.vocesdeayacucho.com/coca-quintucha-huayno-bendito

[viii] Argueda’s body was exhumed and reburied in Andahuaylas but the grave remains as a memorial stone, though local legend seems to suggest that some remains were left in the Angel.