By Eleanor Griffis

✐ OP-ED ☄

Only one week to go and opinion polls are doing somersaults, giving more than a five point lead to Mayor Susana Villaran this week after months of trailing several points behind the recall movement.

That is undoubtedly in response to comments by the recall leader Marco Tulio Gutierrez, who still hopes to bully the mayor into accepting a debate Sunday night. When reminded by a journalist that Villaran has consistently said she will not debate, Gutierrez laughed and said “Ladies always say no and then end up saying yes. That’s what we find so charming about them.”

That is undoubtedly in response to comments by the recall leader Marco Tulio Gutierrez, who still hopes to bully the mayor into accepting a debate Sunday night. When reminded by a journalist that Villaran has consistently said she will not debate, Gutierrez laughed and said “Ladies always say no and then end up saying yes. That’s what we find so charming about them.”

You could almost hear the air being sucked in from the shock. Two days before International Women’s Day. For those of us voting NO, it was a gift from the gods.

There’s been so much color in the headlines in recent months that anyone who has just landed in town could be forgiven for thinking it’s all a bit of a farce. Recalls have been popular for over a decade in the provinces, but this is the first ever held in Lima.

Yet this is no farce. This recall campaign also has nothing to do with ideologies or race or social class, even if the recall promoters are telling you otherwise.

This battle is between transparency and honesty on the one side and corruption, plain and simple, on the other. Between a mayor who practices accountability and a group whose decades-long network of manipulations and kick-backs is being shot down.

As political analyst and former deputy minister of Interior, Carlos Basombrio, says: “This is a battle to the death.” Sociologist Julio Cotler warns of an irreparable break in “institutionality” if the recall is successful.

But then, of course, Susana Villaran was never supposed to have won the mayoral elections in the first place.

The 2011-2014 Election

In 2010, there were nine candidates for the mayoral seat of Lima. The favorite to replace Luis Castañeda was Alex Kouri, the former mayor and later regional president of Callao, despite being questioned at the time for alleged corruption in two major projects in Callao (one court case is ongoing). The alternative favorite was the go-to-candidate for the middle and upper income voters, Lourdes Flores, a seasoned politician.

Susana Villaran, a social-democrat leading the left-wing Fuerza Social, was almost at the bottom of the list.

But then the national elections board ruled that Kouri’s candidacy was not valid because he had not been living in Lima long enough (the port of Callao is a separate province and region). The campaign eventually whittled down to Flores and Villaran, the first with the solid backing of the business community (which now backs Villaran in the recall election) and Villaran with her major support in the lower-income bracket of voters.

It’s worth noting that the only candidates who presented anything close to a development plan for the city were Fernando Andrade, twice mayor of Miraflores and now a member of Congress, and Villaran.

Mud-slinging is part of any political campaign, but attempts to first push Flores out of the way and then finally Villaran were reminiscent of the vicious Montesinos-era tactics, and Villaran’s supporters feared that results might be manipulated. Months earlier, President Garcia —widely quoted—allegedly told a group of business leaders that he couldn’t determine who would win the elections in Peru but he could prevent a candidate he didn’t like from winning.

But Villaran did win the elections, squeaking by with 38.393% of the valid votes, against Lourdes Flores’ 37.1%.

Those who didn’t vote for Villaran were angry and disappointed but few would have actually pushed for a recall. However, their dislike because Villaran was a “caviar” (upper-class leftie) or even a “commie” or “pro-gay” —or even because they sneered at her scarves (absolute truth)— was nurtured by several newspapers and TV news programs, many of which began to describe her as incompetent.

Then in January 2011, when she was actually sworn in, the serious work of building an urban myth about her incompetence began.

Only two months into her administration, a friend of mine remarked casually over lunch that “she hasn’t done anything, has she?” In two months? He was just echoing what everyone else was saying, repeating the pundits on the more classic political TV programs and newspapers.

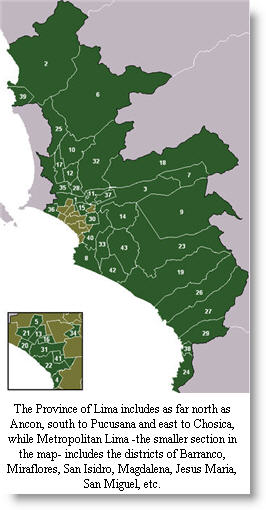

The fact is that in her first two years as mayor, Villaran has invested more and executed more public works than Luis Castañeda did in his first two years, spending an average S/.455 per Limeño against Castañeda’s S/.30. She has also held three times more town council meetings with her 39 council members than Castañeda did in his first two years (he outsourced many decisions), she has added four new hospitals to the Solidaridad network, and she holds more frequent work meetings with the 10 Metropolitan mayors and another 33 of the total number of districts that encompass her responsibility —she was elected Mayor of Metropolitan Lima and Regional President of the Province of Lima. The municipal website, which won official government recognition for transparency in her first year, lists every stage of every project with full financial details, unheard of before.

The fact is that in her first two years as mayor, Villaran has invested more and executed more public works than Luis Castañeda did in his first two years, spending an average S/.455 per Limeño against Castañeda’s S/.30. She has also held three times more town council meetings with her 39 council members than Castañeda did in his first two years (he outsourced many decisions), she has added four new hospitals to the Solidaridad network, and she holds more frequent work meetings with the 10 Metropolitan mayors and another 33 of the total number of districts that encompass her responsibility —she was elected Mayor of Metropolitan Lima and Regional President of the Province of Lima. The municipal website, which won official government recognition for transparency in her first year, lists every stage of every project with full financial details, unheard of before.

And despite fears of her socialist bent, she has secured something close to S/. 4 billion in private investment for city projects. The bid to extend the expressway south to the Panamerican Highway was recently won by Graña y Montero, one of the country’s major construction companies.

Villaran has also taken risks no one else had dared to —she moved the wholesaler’s market La Parada from downtown to new facilities at Santa Anita, a hot potato that had been on the drawing board for close to 40 years; and she has gone beyond Castañeda’s initial Metropolitano public transport project —which she has already expanded— to begin reorganizing and upgrading the entire transport system (new ‘green’ buses, elimination of the fatal combis, upgrading of all public vehicles, reorganization of routes), a project that has led to seven bus strikes and desperate measures by concessionaires who see the lucrative informal side of their businesses at risk.

Mistakes and Bad Luck

Villaran has certainly made mistakes, but they are more form than substance —she was too ready to speak and accept responsibility when for eight years the city had grown used to a mayor who earned the nickname of “The Mute” because he refused to respond to any questions or complaints; she was too slow, says Fernando Andrade, to fire the pro-Castañeda employees undermining her changes; she initially continued to give her opinon on political issues that had nothing to do with municipal government; and she didn’t spend on huge billboards all over town to advertise her successes the way her predecessor had, a diffidence that she admits has cost her recognition for her achievements among the widespread lower income areas.

She has also certainly had her unlucky moments: the increased flow of the Rimac threatened to hold back a tunnel project begun in Castañeda’s term; two months into her administration, the building of the Santa Rosa tunnel —another Castañeda contract— caved in due to a geological failure and is still not safe to resume construction; and the press had a field day when she renovated the long-abandoned Herradura beach front only to find that the truckloads of sand donated by Odebrecht had been washed away by the tide. More recently, two of her own party’s councilmen had to be fired when they were found asking for bribes in a housing program — to her credit, she quickly put the problem to the full municipal council for a vote and made it public on the website.

So, what’s the problem?

Her insistence on accountability and transparency is ruining the lifestyle of a lot of people — not only those entrenched in an intricate web of concessions worth millions of soles a month in the transport system that she is turning around completely, but in every other aspect of municipal government — building permits, commerce licenses, zoning —where outsourcing and commissions from someone else’s commissions are no longer the way the municipality operates.

However, her “great, great” mistake, says Roque Benavides, CEO of Peru’s leading gold and silver mining company, Buenaventura, was to criticize Luis Castañeda as heavily as she did when she first entered city hall. “You pay for political errors,” he told TV journalist Beto Ortiz.

“She just doesn’t have ‘muñeca política’,” a friend tells me, implying she doesn’t have the political savvy to know how to work with the long established network.

“I’m not naïve,” Villaran said in an interview with Ideele magazine, “I just do politics differently. I don’t think one has to trample on principles to be in politics and be successful.”

One of the first steps taken by Villaran as mayor was to order an audit of the previous administration, just as Castañeda did with his predecessor, Alberto Andrade.

Castañeda was already under judicial scrutiny for what is known as the Comunicore case (see note at the end), but what the audit also showed was that there were a lot of other questionable areas and financial decisions —a list that includes the Taxi Metropolitano system, the weakening of the Caja Metropolitana savings and loans bank, and an increase in almost every project budget way above the standard 20% (the management of more than 50% of the city’s projects was outsourced to the local office of the International Organization for Migration, IOM, and therefore not subject to financial supervision by the Comptroller General).

Villaran’s mistake was to personally present the audit findings, rather than assign a spokesperson to do so. And the problem for Castañeda, of course, was that the findings were released only weeks before the presidential elections, which he hoped to win based on his track record as mayor.

So, who are the “Revocatoria” team?

Although it is generally believed that Castañeda is the driver behind the movement —he has never said so publicly but recently admitted he would be voting for the recall, and the posters and T-shirts of supporters are in his party’s classic yellow— the public face is Marco Tulio Gutierrez, a lawyer who on a TV show almost five years ago accused Castañeda of financial mismanagement and later became, as he readily admits, a paid external advisor to Castañeda at the municipality.

Although more in the background, the Fujimori supporters are also backing the recall.

Gutierrez’ support team —which helped him collect 400,000 signatures for the recall, handing out packets of noodles and biscuits— is worthy of one of those crazy Italian comedies of the 1960s: one faces criminal charges for stealing real estate and says God brought him into the world for this precise recall mission, while another is a former evangelical pastor ousted from his church decades ago and still facing current court charges on coercion, indecent assault and extortion. The initial list of campaign financing disclosures, investigative journalists discovered, included the name of a man who was long dead and another who was a former national intelligence agent who was facing eviction because he could not even pay his own house rent.

The pro-recall campaign tactics have certainly been dirty enough — fabricated charges of fraud and embezzlement, city project billboards torn down, protesters sent to stand outside Villaran’s home to shout insults with a megaphone, while others destroyed and burned down two new children’s playgrounds in the San Juan de Lurigancho district. In some districts where the mayors are pro-recall —such as San Juan de Lurigancho, Jesus Maria and Chorrillos— pro-Villaran supporters campaign at their own peril.

When the polling results began to show a narrower margin between both sides of the recall, the Apra party joined the campaign against Villaran, adding its own unique flavor —the racial and social class accusations, for instance— and former President Alan Garcia’s open support. However, Apra’s support could be harming the recall movement, judging from the dip in the polls, not surprising since not only Garcia but most of his former ministers are under investigation for corruption during their administration.

Villaran, on the other hand, is being backed publicly not only by all the classic left-wing intelligentsia and center-right political leaders such as her former contender Lourdes Flores and former President Alejandro Toledo, but also by popular celebrities from the entertainment and sports worlds and figures such as Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa and former UN Secretary General Javier Perez de Cuellar.

Whether this cream of the crop can convince people who don’t like Villaran —at both ends of the socio-economic scale— to vote for her, is yet to be seen.

What can happen in this week is anybody’s guess. At least we can thank the papal enclave for the fact that Cardinal Cipriani is busy voting in an unrelated election at the Vatican and won’t be using his Saturday radio program to warn us against the dangers he perceives in allowing Susana to continue changing the status quo in city hall.

______________The Comunicore Case_____________________________

In the words of Carmen Gonzalez, psychotherapist, radio commentator, and columnist in Peru.21: The Lima Municipality recognized that it owed the Relima garbage collection company an old debt of S/.35 million and reached an agreement to pay it over a period of 10 years. Relima sold its rights to Comunicore for S/.14 million in cash. Comunicore then reached an agreement with the Municipality to receive the S/.35 mn, not in 10 years but in one month. It paid Relima the agreed S/.14mn, and with the balance it distributed S/.4 mn among its managers, which included the husband of a niece of Castañeda. And the remaining S/.16mn? They hired 30 humble people from [the district of] Comas: they gave each of them S/.100 to go to the Banco de Credito and BBVA Continental to cash checks for the millions, which immediately evaporated. Then, before disappearing, Comunicore went to a notary in La Oroya and changed its name to Consorcio Esaróstica, the maternal surname of its manager, a woman who was illiterate. And Castañeda? Well, you see, he had nothing to do with it because just then he had asked for vacation time. Wasn’t he lucky!

_____________________________________________________________________