By Nicholas Asheshov

– Special for the Machu Picchu Centennial –

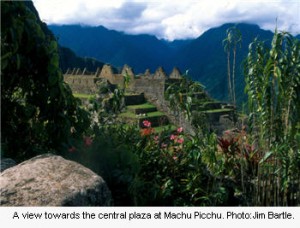

Machu Picchu and the Inca Empire were the creation of an import from Central America, maize, and a dramatic climate shift that turned the Andean highlands from inhospitable wet-and-cold to pleasant, as it is today, dry-and-warm.

For more than half a millenium before this shift the high Andes had been miserable. With the new dry-and-warm, starting around 1000 AD, a backwoods tribe, the Incas, put together the new climate and technology breakthroughs and by 1500AD had produced the world’s most go-ahead empire, heavily populated and larger, richer, healthier and better organized than Ming Dynasty China and the Ottoman Empire, its nearest contemporaries.

The Incas, like a score of tribes all over the tropical Andes, had moved up over the previous millenia from hunters-and-gathers to llama-herders and, latterly, agriculturalists, farmers of potatoes and quinoa, the top names among a world-class agricultural flora that was famously described in the National Academy of Science’s The Lost Crops of the Incas (1989).

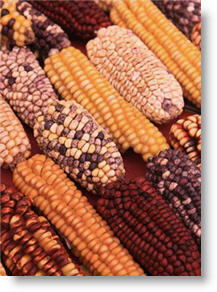

Then came maize. New studies, the latest just published in London by Alex Chepstow-Lusty, the Cambridge archeobotanopalaentologist, show that high-altitude, large-kernel maize suddenly became widely established around 2,700 years ago – 700BC.

Then came maize. New studies, the latest just published in London by Alex Chepstow-Lusty, the Cambridge archeobotanopalaentologist, show that high-altitude, large-kernel maize suddenly became widely established around 2,700 years ago – 700BC.

Alex’s work is based on core samples he took from Marcacocha, a pond at 3,350ms asl just 30 miles upstream from Machu Picchu itself.

They provide a high resolution (40-100-year) environmental and agricultural history of the heart of the Inca region over the past 4,200 years, encapsulated within 6.3 meters of well-dated, highly organic sediments.

In these core samples the maize opal phytoliths first appear in 700BC, early on in an earlier warm-and-dry cycle.

The samples record, in general terms, a 500-year cycle of warm-and-dry alternating with another half-millenium of cold-and-wet, though the past 500 years haven’t been as bad as earlier events.

Analysis of maize opal phytoliths from four archaeological sites in the Copacabana Peninsula, Lake Titicaca, have also come up with a date for the appearance of commercial maize of 2,750 years ago. Even though Lake Titicaca has always provided a special solar-heated mini-climate, at 4,000ms asl this is an astounding height for a species that started its career in muggy Yucatan 7,000 years ago.

Maize, together with new weeding techniques, irrigation, fertilizing and genetic selection, was to transform the Andes into a center for a succession of productive civilizations, starting with Tiahuanaco around Titicaca itself. The Andes were, as the Cambridge archaeologist David Beresford-Jones puts it, “one of humanity’s rare independent hearths of agriculture.”

“Maize was the last piece in the puzzle of the Andean agricultural package, which allowed an expansionist agricultural intensity threshold to be crossed,” says Alex’s latest study, just published in Antiquity, London.

Recent stable isotope analysis of the bones, taken to Yale by Hiram Bingham a century ago, show that the main item in the diet of the inhabitants of Machu Picchu was not the potatoes and high-protein quinoa native to the Andes, but maize.

Recent stable isotope analysis of the bones, taken to Yale by Hiram Bingham a century ago, show that the main item in the diet of the inhabitants of Machu Picchu was not the potatoes and high-protein quinoa native to the Andes, but maize.

The Incas got their kick-start to fame with the global warming that was also underway in Europe. It was this climate change that allowed Western Europe to emerge from the cold-and-nasty Dark Ages.

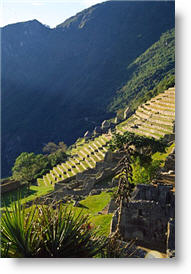

At the same time as the Middle Ages in Europe were blossoming into the Renaissance, the Incas were developing a sensational re-construction of the natural verticality of the Andean landscape. They created thousands of well-drained flights of level stone terraces, unequalled anywhere, covering whole valleys. Turbulent river-courses were channeled and walled.

Not only did the population explode, but the Incas knew how to marshal this key resource. They would put thousands of workmen onto the job just like a modern engineering concern.

The Inca understanding of stone, of construction and of hydrology is described by Kenneth R. Wright, a prominent engineer from Denver, in his first-class Machu Picchu: A Civil Engineering Marvel (2000).

Few of the Inca terraces are in use today. The complicated irrigation flows and long source-channels have fallen into disuse. What they did was to make the best, in the dry-and-warm cycle, of the snow-melt, rivers, streams and lakes, ensuring that agricultural production remained high even during long droughts. Now that we ourselves are into a new global warming it’s certainly time to see how the use of these super-terraces might be resuscitated.

Few of the Inca terraces are in use today. The complicated irrigation flows and long source-channels have fallen into disuse. What they did was to make the best, in the dry-and-warm cycle, of the snow-melt, rivers, streams and lakes, ensuring that agricultural production remained high even during long droughts. Now that we ourselves are into a new global warming it’s certainly time to see how the use of these super-terraces might be resuscitated.

The empire was pulled together by thousands of miles of all-weather stone roads and a warehouse network with two or three years worth of strategic reserve food and clothing. These were immediately ransacked, of course, by the Spaniards when they took over in the 1530s.

Bureaucrats, another feature of empires, were prominent. Gary Urton at Harvard has shown that the khipu, knotted, colour-coded cords, was a complex mathematical and legal record system that was certainly as competent as the double-entry book-keeping that was being introduced in Europe at that time. Much easier to transport and store, too.

Quinoa, a chenopod not a true grain, is much richer in protein than all true grains, so the pre-maize potato+quinoa Andean diet sounds rather healthy.

But cereals, starting with wheat, barley, oats in the Middle East and, in the Far East, rice, have invariably provided the high-volume calories that empires need to support cities and armies. No cereal, no empire.

Graham Thiele, of the International Potato Center in Lima, tells me: “Potatoes are bulky and perishable. So maize has a huge advantage. It was the transportablility of maize, even more than the productivity, that made it a key part of the Inca scheme.”

Maize, he adds, is easy to store, while potatoes go bad and get ruined quickly by bugs and blight.

I have to say that this new emphasis in the historical record on high-altitude maize comes as a surprise to me, even though I live in the heart of Urubamba, 2,840masl, one of the great maize valleys of the Andes. I have always thought that potatoes were the true Andean basic, with hundreds of varieties backed by a cultural tradition akin to that of rice in China. By the way, the International Potato Center tells me that China is today –surprise— the world’s top grower of potatoes and camote (sweet potatoes).

I have to say that this new emphasis in the historical record on high-altitude maize comes as a surprise to me, even though I live in the heart of Urubamba, 2,840masl, one of the great maize valleys of the Andes. I have always thought that potatoes were the true Andean basic, with hundreds of varieties backed by a cultural tradition akin to that of rice in China. By the way, the International Potato Center tells me that China is today –surprise— the world’s top grower of potatoes and camote (sweet potatoes).

When the last big-cycle global warming began around 1,000AD, the established regimes in the southern Andes, Tiahuanaco and Wari, were unable to adapt and the Incas moved in.

Fashionable economists and political scientists today have started to call this “the advantage of backwardness.” This intends to explain, for instance, why China, India and Brazil, basket-cases three decades ago, are suddenly leaping forward into the top ten.

A favorite instance are the Romans around 300BC who, regarded as crude barbarians by the Greeks, Persians and Egyptians, quickly took them over and created the world’s best-loved empire.

In the Peruvian Andes the Inca country cousins out in the Cuzco boondocks reacted quickly to the drought while the entrenched Wari sat, watched, and disappeared. Their impressively sad capital, Pikillacta, an hour south of Cuzco, is next door to the parish church at Andahuaylillas, the ‘Sistine Chapel of the Andes.’ Gordon McEwan’s masterly Pikillacta: The Wari Empire in Cuzco (2005) is the sourcebook.

Today the Incas would have won the Nobel prize for agriculture, architecture and another couple for conservation. They planted high-altitude polylepis forests to encourage and capture rain in the high cordillera. We have cut most of these down for firewood.

Like the Romans the Incas brought in talent. The stonemasons of Tiahuanaco, metallurgists and goldsmiths from the Coast and agriculturalists from the North.

Sadly for the Incas, there was to be no advantage when the Spaniards arrived, to their backwardness in warfare. It took less than five quick years for a handful of Spanish warriors to destroy the monumental achievement of five centuries of a civilization that was built, as Machu Picchu shows, to last forever.

NOTES:

Richard Webb, former President of the Central Reserve Bank, comments that the concept of the Advantage of Backwardness was created by Alexander Gerschenkron, a Vienna-educated Russian who was in charge of economic history at Harvard and influenced a generation of economists there, including Webb. “His examples were Germany, France and Russia, which all benefited from lagging after England during the 19th century.”

Hugh Thomson, the film-maker and author of The White Rock and of Red Cochineal, both on travel and the pre-history of Peru, comments:

“I am not sure that the transition from Wari to Inca was quite as seamless as you make it sound (‘the Inca country cousins out in the Cuzco boondocks reacted quickly to the drought while the entrenched Wari sat, watched, and disappeared) – the model I’ve usually heard is Wari decline around 1000 A.D. , for climatic reasons, slow emergence of Incas from around 1300 AD, ‘full-on’, to use an archaeological term, expansionist Inca period from after 1400 on, although I know that this early Inca period is constantly being re-evaluated by Bauer and others.”

David Beresford-Jones, the Cambridge archaeologist and author of the just-published Lost Woodlands of Ancient Nasca‘ (Oxford University Press), comments:

“Excellent… The point about maize, for which Alex’s work (among others) provides real data, builds upon an argument that the Andean linguist Paul Heggarty and I make in a 2010 article in Current Anthropology, ‘Agriculture and language expansions: limitations, refinements and an Andean exception?’

“But I am not so sure about the detail of how you portray Wari. For I’d say that all of the elements of statecraft that we think of as Inca: roads, khipu recording systems, and intensification of maize agriculture through terracing and irrigation, in fact had their roots in the Wari Middle Horizon. Indeed, Paul and I would argue that we should add to that list another element still popularly associated with the Inca Empire: the Quechua language family.

“This is developed in another article of ours making that case, ‘What role for language prehistory in redefining archaeological culture? A case-study on new Horizons in the Andes’ recently published in Investigating Archaeological Cultures: Material Culture, Variability and Transmission, edited by Roberts, B and Vander Linden, M., pp. 355-386. New York: Springer.

Gary Ziegler, the archaeologist and explorer comments: “The transition from Wari decline to Inca expansion remains one of the great enigmas in Inca study.

“The fall of the Inca was historically determined by the arrival of epidemic disease (likely Bartonellosis from Ecuador and the resulting war of succession following the death of Huayna Capac, not European military superior capability. I suspect Topa Inca would have made quick work of Pizarro’s handful of raiders had they arrived a few decades earlier.

“It is interesting that maize apparently did not get to North American until around 800 AD. This probably allowed the development of the advanced Mississippi and Anasazi polities.”

Vince Lee, the architect and Vilcabamba explorer, commenting on Nick Asheshov’s piece and on the Wari/Inca connection, refers here to the Wari tombs found recently by INC archaeologists at Espiritu Pampa. Espiritu Pampa, identified by Gene Savoy in 1964 as the true last refuge of the Incas, is down in the jungle beyond Machu Picchu. The discovery of the Wari tombs has set off speculation of a close connection between the Wari and the Inca, but Vince Lee doubts it. He says:

“The Wari tomb is not in the midst of the Inca ruins, but several hundred meters away. So it does not look like the Incas found or simply reoccupied an earlier Wari site. As you may know, there are several hundred years separating the decline of the Wari from the rise of the Incas. When I first went there in 1982, Espíritu Pampa was covered by thick rain forest and looked exactly as it did to both Hiram Bingham in 1911 and Gene Savoy in 1964. The growth was so thick that even finding the ruins took quite a bit of work in 1982. I mention this to suggest that a Wari site abandoned there for several hundred years would have virtually disappeared long before the arrival of the Incas.

“I note that lots of speculation is turning up that attempts to somehow connect the Wari and Inca cultures via this find, but I’ll be surprised if future work confirms this.

Graham Thiele, at the International Potato Centre, Lima, is concerned that “a reader could get the wrong end of stick and think potatoes are not important in the Andes.

“The article appears to say that maize is superior in an absolute sense to potato, but my argument was more nuanced. Potatoes would still have been a key part of local food systems but because of bulkiness are not suitable for longer distance trade and surplus extraction. Hence potato then as now could have been a key part of the diet of the poor (esp at higher altitudes) but not widely traded. The part about potatoes rot easily is a bit overstated as under higher altitude conditions potatoes can be stored for several months, just not as long as maize.”