By Paul Goulder —

The Britanico, as many in Lima will know, refers to the Asociacion Cultural Peruano Britanica (ACPB) which, amongst its other virtues, is one of Lima’s most prestigious language schools. Tens of thousands of students have passed through the doors of its eleven premises in the herculean task of learning English. In addition to its study and research facilities (the Av. Arequipa premises have a good English-language library) the Britanicos have a range of daily cultural activities.

The association was founded seventy-five years ago at a critical time[1] for Europeans living in Peru.

Confidence in the future

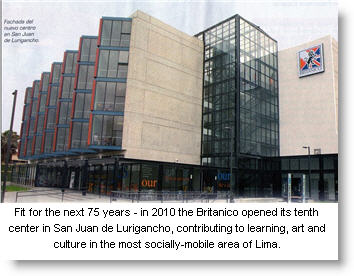

The centers are located variously from Miraflores on the coast to San Juan de Lurigancho – the town within a city which is not much more than thirty years old. By opening a large, well-designed Britanico there the vibrancy and viability of the “new” Lima has been recognized and somehow makes for one of the best markers of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the ACPB: not the end of an era but the beginning of the next.

The centers are located variously from Miraflores on the coast to San Juan de Lurigancho – the town within a city which is not much more than thirty years old. By opening a large, well-designed Britanico there the vibrancy and viability of the “new” Lima has been recognized and somehow makes for one of the best markers of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the ACPB: not the end of an era but the beginning of the next.

Their seventy-fifth anniversary logo reads “75 years exchanging (intercambiando) cultures” and has two call-out balloons presumably inter-communicating with each other: Britain with Peru. Years ago it might just as well have been Miraflores with Lurigancho, when the cultural gap with the Andean cultures, in the positivist and marginalist[2] eras, was perhaps greater than that with the UK.

Their seventy-fifth anniversary logo reads “75 years exchanging (intercambiando) cultures” and has two call-out balloons presumably inter-communicating with each other: Britain with Peru. Years ago it might just as well have been Miraflores with Lurigancho, when the cultural gap with the Andean cultures, in the positivist and marginalist[2] eras, was perhaps greater than that with the UK.

While the Britanico in San Juan de Lurigancho sets the trend for the future, the principal cultural center at Jiron Bellavista 531, Miraflores (theatre, auditorium/cinema, and gallery) has as its opening salvo for the 75th celebrations an exquisite exhibition of pre-Hispanic textiles, mostly from the Chancay Culture (1200 to 1450), and a selection of Chancay ceramics.

Rather than explicitly filling their Harriman Gallery with a record of past achievements in the cultural projection and languages business, this exhibition provides a “purist statement of abstracted beauty”, and rather than explicitly telling a history of textiles it concentrates on the form of presentation. Brilliant.

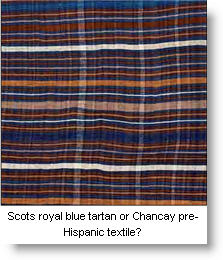

They might have been tempted to “draw out a thread” suggested by one or more of the pieces. For example, this virtually contemporary piece from about 1300 (Chancay cuture) could almost have been from the Scottish highlands: a MacChancay tartan perhaps. However, that would have ended up as contrived and perhaps trite.

Braced by this exhibition of high quality “artesania becomes art”, the viewer is left to ruminate on the subject of 75 years. Here the Peruvian Times can help. It is rather more than seventy-five years old (its precursors Peru Today and the West Coast Leader date back to 1908) and has archives brimming with items relating to cultural links. I would say it is the premier research archive for those seriously researching Anglophone – Peruvian relationships.

Braced by this exhibition of high quality “artesania becomes art”, the viewer is left to ruminate on the subject of 75 years. Here the Peruvian Times can help. It is rather more than seventy-five years old (its precursors Peru Today and the West Coast Leader date back to 1908) and has archives brimming with items relating to cultural links. I would say it is the premier research archive for those seriously researching Anglophone – Peruvian relationships.

This essay, thus, is surveying the “opening shot” in a revue of the long history of “intercambiando” culture. As if to say that the Central Coast area of Peru – in any cultural exchange – has this refined, sophisticated textile culture to offer as an initial bid. Now, let’s see what you (the rest of the world) can come up with?

By the time (1820’s) the rest of the world could respond, having been excluded by the Spanish Empire, the Flemish-French had invented the Jacquard loom[3] and Britain was well on the way to industrializing textile output completely.

From more than one source I have received comments of the type “How appropriate to use textiles in the 75th anniversary exposition – the most enduring of Britain’s links with Peru have been in the textile industry”. Others see other connections.

However, drawing out the threads posed by the abstraction of the exhibition are essays in themselves and will be left to Essay II (Textiles: Britain, Peru and Arequipa 1821 to 1937) and Essay III (75 years ago: Britain and Peru).

Today we look at the textile exhibition itself.

Early influence

“Contemporary European artists at the beginning of the 20th century —such as Modigliani, Picasso and Matisse— were the first[4] to recognize what was considered ‘primitive art’, incorporating a synthesis of what these pieces offer into their work.”

The visitors to the Britanico’s Harriman Gallery, if they arrive after 4 pm, are treated to personal or small-group guided tours. In our case, on the two occasions we were escorted round, by Jonathan and Julisa, respectively – both graduates of art history from Lima’s historic and academically-competitive San Marcos university – both demonstrated a knowledge of and indeed love for the works.

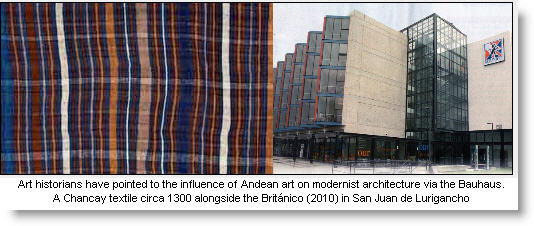

One very intriguing aspect mentioned was the influence of ancient Andean art and weavings on the modernist movement. The camera having somewhat displaced Canaletto-style representative and figurative painting, artists from about 1860 started exploring other forms of expression: expressionism itself and various techniques of abstraction —some inspired by what was then called “primitive art.” [Primitive in this sense signifying reductionism, pure, simplified and not derogatorily “less-developed” as the word primitive is generally used today].

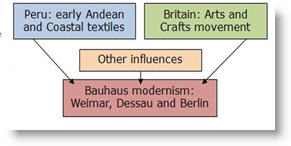

In the case of the somewhat later Bauhaus group, Joseph and Anni Albers, Paul Klee and others visited or were influenced by the great Ethnological Museum in Berlin to which, for example, archaeologist Max Uhle had sent thousands of Andean and Coastal pieces, as he had also sent to his sponsoring university in the United States.

First let’s rotate the “MacChancay” weaving 90 degrees and set it alongside the architecture of the Britanico’s San Juan de Lurigancho center – (which, designed by architect Reynaldo Ledgard, has elements of modernism) and —following the Albers’ work— the suggestion is that the quintessential “prime”-itive intensity of the weaving offers an artistic guide to colors and the “correct” use of strong horizontals and vertical urdimbres[5]. And much more, but here we must depend on the imagination of the reader and the architect.

The Blues

In passing, note also the use of blue dyes in the fibers in this weaving. Blue appeared relatively late in Andean textiles – the color being from a mineral and not from plant, animal or biological sources. Europe did not have a satisfactory “blue” until the 11th century – though of course it extracted woad coloring – supposedly the color of choice for pre-Roman warriors.

So the MacChancay textile might have been an exogenous influence on the Modernist movement if only “she” had been collected by Max Uhle and been available for viewing by the Bauhaus innovators.

An indirect British link

But where is there a British or anglophone link in all this? Well, another exogenous or outside source of inspiration for modernism, at least in architecture, is that of the Arts and Crafts movement which took off in industrial late-nineteenth century Britain as a response to the “dark satanic” depersonalizing forces of factory production.

But where is there a British or anglophone link in all this? Well, another exogenous or outside source of inspiration for modernism, at least in architecture, is that of the Arts and Crafts movement which took off in industrial late-nineteenth century Britain as a response to the “dark satanic” depersonalizing forces of factory production.

Intriguingly, the outside wall of a building in the Gropius or Mies van der Rohe (key Bauhaus directors and architects) style is often referred to by a textile term: the “curtain” wall – a term since generalized.

Specifics

The exhibition includes textiles from way, way back – two extremely fragile and faded pieces go back to 1000-200 BC (the Chavin horizon). Such fragments are extremely rare. Imagine finding Socrates’ (Golden Age of Greece) shirt in a museum. Rarer even than the Gold medal we hope contemporary icon Claudia Rivera, Peruvian champion, will achieve in the forthcoming badminton section of the 2012 Olympics.

A textile index

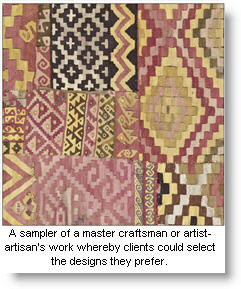

One of the most intriguing textiles in the exhibition is composed of samples of various designs, which could have been used by master craftsmen to entice their potential clients into purchasing their weavings (but not with money – as yet to be invented) or for the elite to choose the pattern they require. An AD 1200 version of an online catalogue!

One of the most intriguing textiles in the exhibition is composed of samples of various designs, which could have been used by master craftsmen to entice their potential clients into purchasing their weavings (but not with money – as yet to be invented) or for the elite to choose the pattern they require. An AD 1200 version of an online catalogue!

This sampler comes from Chancay (the origin of many of the exhibits), a valley north of Lima noted for the high quality of its textiles. Their ceramics on the other hand are comparatively bland. This complex textile (or textile complex) is more beautiful indeed than an Argos (Sears, or whatever) catalog and serves as a form of index to the creations of the artist-artisan.

In an era when figurative or representational design was little used, at least for entombing purposes, one “person” creeps into this sample of a sampler – perhaps a type of signature of the artisan. But that is speculation.

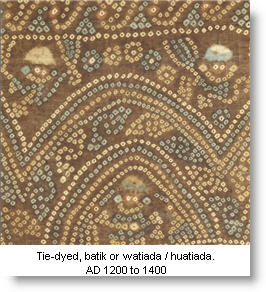

Think of it this way: think of each of the elements in this highly detailed design (right) on a magnificent cotton fabric, as a sort of pixel (those little dots on the computer screen which can be switched on or off to produce varying colors). Here the switching is done by tying a tiny circle of fabric so tightly that when immersed in a dye the surrounding area takes up the color(s) of the dye – but not the tied part. The process is infinitely time-consuming and is termed, logically enough, tie-dying in English, but batik or watiada in Peru.

One of eight

Multiply this exceptional image, (right), which is the size of a large chess board, by eight and you gain an idea of the size of textile used for (probably) wrapping those who have died – in order to set them up for life in the afterworld. The whole textile is displayed vertically, which entailed a laborious process of stretching and stitching to the backing material and might involve two or four expert professional textile restorers, situated both sides of the fabric.

This could be an early Peruvian “Gobelin” though almost certainly not used as a wall hanging.

The team conserving and preparing for the exhibition, including intern experts from Japan, needed three months for the tasks. The expense is incalculable – at least on our small calculator – and the Britanico was quick to express its gratitude to the Amano Museum for the loan and for help with the presentation.

The Amano was founded by Yoshitaro Amano (1898 Akita, Japan – 1982 Lima, Peru), who arrived in Peru five years after the 2nd World War. The Museum opened on 22 August 1964 but is still relatively off the beaten tourist track.

Yoshitaro Amano’s achievements are all the more remarkable given that he left a Japan still recovering from the immediate aftermath of the war and had the foresight and sensitivity to appreciate the value of the Chancay textiles that huaqueros initially had cast aside and few in Lima at that time held in any esteem.

Yoshitaro Amano’s achievements are all the more remarkable given that he left a Japan still recovering from the immediate aftermath of the war and had the foresight and sensitivity to appreciate the value of the Chancay textiles that huaqueros initially had cast aside and few in Lima at that time held in any esteem.

Precursors

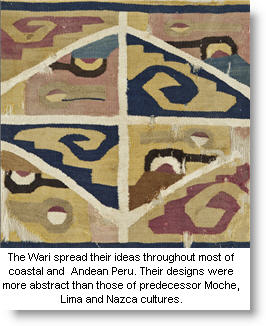

As many historians insist today: we “stand on the shoulders” of somebody! The Romans on the Greeks, Japan on those of China, and Chanchay in all probability on those of the Wari. There is one endearing piece that evidences the passing of time but that nevertheless seems to capture several elements of Wari (Huari in Spanish) iconography. Almost a stereotypical piece.

_________________________________

Next: The Peruvian Times will explore further one idea prompted by the exhibition. Weavings and textiles not only are a “vehicle” for cultural exchange but have been a major element in Britain’s relationship with Peru. Both Bradford (Yorkshire, UK) and Arequipa were transformed during the course of the nineteenth century by textile industries, including the commerce in wool and fibers. The introduction of alpaca fiber was the principal innovation and the families involved in this episode of the first industrial revolution have left an indelible cultural mark. The next article is a report from Arequipa.

___________________________________

[1]This will be explored in Part III; [2]Sociologists sometimes categorize Peru’s stages of development as patrimonialism, positivism, marginality, developmentalism, globalism; [3]The beginnings of computer-controlled weaving; [4]This is quoted from the literature accompanying the exhibition; [5]Urdimbre signifies in weaving the warp and also, metaphorically, scheme and intrigue.__________________________________

Paul Goulder: Academic and specialist on Latin America and Peru. Last academic posts: ENSCP-Paris; King’s College, University of London; UNSA, Arequipa, Peru. Also not-for-profit work in ecology, development and education in UK and Peru.______________________________